Transparency, Accountability and Assurance in Nuclear Security

Nuclear security is a term that can cover a range of issues including materials security, arms control, nonproliferation, etc. In this discussion it is used in the specific context of protection of nuclear materials against unauthorized acquisition, and protection of nuclear facilities against sabotage. [1]

In January 2012 the Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI) released the Nuclear Materials Security Index, a benchmarking project of nuclear materials security conditions on a state-by-state basis. A major recommendation of the Index was that all states must work together to build a system for tracking, protecting and managing nuclear materials in a way that builds confidence that each state is meeting its security responsibilities. Accountability will be an essential element in this system.

Currently a deliberate lack of transparency about security measures makes it impossible to hold states accountable for their security responsibilities. Accountability – for which transparency is a necessary condition – helps to ensure states meet their international commitments, to identify areas requiring improvement, and to target international cooperation and assistance.

The Nuclear Materials Security Index called for states to show greater transparency about their nuclear security efforts. The Index noted that transparency:

… is an important concept in international security. It is widely used to describe various forms of openness that enhance public and international confidence and understanding and minimize misperceptions.

The Index has prompted a discussion of the relationship between nuclear security and transparency. Some commentators have gone so far as to suggest that transparency and nuclear security are mutually contradictory. Such comments highlight the need for a proper understanding of the role and importance of transparency in the nuclear security context.

Transparency

Transparency describes a condition or state of openness, communication, and accountability. Readers may be familiar with the use of transparency in nuclear disarmament and arms control, as well as more broadly in areas well beyond nuclear affairs. No doubt concerns about transparency in nuclear security reflect the novelty of the term in this particular context, and some confusion about what transparency might involve. One response to these concerns would be to find alternative terminology, such as confidence-building measures, assurances, accountability mechanisms, or a responsibility to report. However, transparency is such a convenient term that it seems preferable to retain it and to develop a common understanding of its meaning.

Historically – no doubt reflecting the nuclear era’s military beginnings – national sovereignty and secrecy have been the predominant mindsets in nuclear security. By comparison, in nuclear safety international governance has been progressively strengthened.

In nuclear safety the historical attitude has also been one of resistance to international oversight. This attitude continues today, for example, there is opposition to any form of international safety inspection. Nevertheless, each major nuclear safety crisis has led to significant advances in international governance – the nuclear safety community has come to accept that nuclear safety involves international responsibilities. In the most recent example of this evolution, following the Fukushima accidents the World Association of Nuclear Operators (WANO) has decided on mandatory peer reviews in nuclear safety, something that currently seems anathema to the nuclear security community.

A culture of secrecy is actually contradictory to good nuclear security culture. Secrecy risks masking complacency and inadequate performance – leading to security vulnerabilities that could endanger not only the state concerned but the broader international community. We must ensure it does not take a catastrophe before nuclear security attitudes change.

The Need for International Accountability and Assurance in Nuclear Security

It is no longer good enough for governments to say “trust us”, accountability is both a legitimate and a necessary expectation. This is the case not only for nuclear security, but for all aspects of managing the nuclear fuel cycle. Fukushima has demonstrated that nuclear events can have an impact well beyond the borders of any one state. States engaging in nuclear activities have a responsibility to manage them effectively and to provide the international community with assurance to this effect.

The 2010 Nuclear Security Summit recognized that nuclear security is only as strong as the weakest link – if terrorists succeed in acquiring a significant amount of weapons-usable material in any state, this would present a threat, directly or indirectly, to the international community at large. Likewise, any event that results in large-scale radiation release will have a global impact, if nothing else on public and political confidence in nuclear energy.

The 2010 Summit affirmed that nuclear security is a shared objective, requiring sustained and effective international cooperation. In view of this strong international interest, nuclear security can no longer be seen as the exclusive prerogative of individual states. While each state is responsible for its domestic nuclear security regime, it also has a responsibility to others to fulfill its national responsibilities effectively. The state has a responsibility to provide the international community with confidence that effective security measures are being applied. There is a clear parallel with safety and security in the aviation industry, where transparency and information-sharing are now seen as being essential.

Providing confidence requires appropriate mechanisms for information-sharing – so that others know the state is meeting international expectations, and so the state is able to identify areas for improvement. Information-sharing is also important for international cooperation, so states can request or offer support and assistance where needed.

Transparency and Nuclear Security Objectives

Key objectives in nuclear security

- Effectiveness – ensuring that security measures can be relied on to counter the threat, in particular that they reflect best practice

- Assurance – giving other states confidence that national responsibilities are being implemented effectively

Ensuring effectiveness is both a national and an international responsibility. At the national level, the state has an obvious self-interest in ensuring its domestic security regime is operating effectively. Because any security failure could have serious consequences for other states, ensuring effectiveness is also an international responsibility. Providing assurance about effectiveness is an essential aspect of this international responsibility.

The objectives of effectiveness and assurance are closely related – a state cannot provide assurance to others about its nuclear security arrangements unless it is able itself to properly assess the effectiveness of these arrangements. Both objectives require engagement and information-sharing necessary to enable comparative evaluations by the state and by the international community. The objective of providing assurance necessarily involves accountability – which in turn requires an appropriate level of transparency.

Exactly what transparency means will depend on the particular information and the particular context. Some information can, and should, be shared with the public. Other information might be shared on a confidential basis with other governments or the IAEA. Certain information that is more operational in nature might be shared with a trusted partner. [2] There will be site-specific information that should not be shared, but such information is only part of the totality of information related to nuclear security.

Evaluating Effectiveness

A state cannot assess its own security performance in isolation – as part of performance benchmarking the state must have a practical knowledge of international best practice. Quality assurance principles require that actual performance and best practice are subject to a process of continuous improvement. Application and improvement of best practice require engagement with other practitioners. Thus international engagement is a necessary part of good security culture. There are various mechanisms for international engagement, involving interaction with other governments (including with a trusted partner), the IAEA and WINS. [3] Practical mechanisms include the IAEA recommendation process, expert workshops, bilateral or multilateral advisory missions, and peer review.

External peer review in particular is a vital mechanism for providing confidence in both directions – to the international community and to the state itself – and is also an important aspect of international cooperation, helping to identify areas for improvement.

Peer review is a process of evaluation by independent experts in the relevant discipline. For example, a peer review under the IAEA’s International Physical Protection Advisory Service (IPPAS) typically involves a team comprising IAEA representatives together with experts drawn from several states, acting on behalf of the IPPAS mission rather than in their national capacity. If a state requests an IPPAS review, the team will visit the offices and facilities made available by the state and will make recommendations based on their observations. WANO’s peer review practice is broadly similar – the reviews are conducted by an independent team comprising experts drawn from other WANO members. WANO reviews are conducted by peers of the facility staff hosting the review, who have a unique appreciation for the job. They know what operators face every day, because they face the same issues themselves. WINS offers nuclear security peer reviews that are similar to the WANO model.

There have been concerns expressed about the idea of sharing more-specific information relating to security practices, including through peer review. States should not cite confidentiality as a reason against international engagement and accountability. The state’s responsibility to protect the confidentiality of security-related information is not a license to maintain secrecy over all such information, only information the unauthorized disclosure of which could compromise the security of nuclear material and facilities.

A state inviting peer review, whether through the IAEA, WINS or bilateral arrangements, maintains full control over what information is available to the reviewers. There is no reason why peer review should risk compromising secrecy of site-specific arrangements. The host state can apply whatever managed access arrangements it considers necessary.

Providing Assurance

Providing assurance is a matter of considering what actions a state should take to ensure effective nuclear security, and demonstrating this to other states. A state should participate in relevant regimes and demonstrate fulfillment of the requirements of these regimes. Participation in relevant regimes such as the Convention on the Physical Protection of Nuclear Material (CPPNM) and its 2005 Amendment, the Nuclear Terrorism Convention [4] and Security Council Resolution 1540 are important elements in demonstrating a state’s commitment to materials security − but more is needed.

It would go a long way towards providing international assurance about a state’s performance of its nuclear security responsibilities if there were a specific transparency mechanism, such as a reporting procedure, by which the state can show that it is taking the appropriate steps. There is nothing inherently sensitive about reporting on implementation (e.g. the existence of regulations) other than perhaps for the wrong reason – some states may be sensitive that they have not met international expectations in these areas.

Currently there is no such transparency mechanism. Following the 2010 Nuclear Security Summit, Australia circulated to the Summit Sherpas a proposed national report pro forma, completed with Australia’s details to show there was no particular difficulty in preparing such a report, but regrettably this example was not taken up by others.

Absent a mechanism of this kind, NTI included a specific transparency indicator in the Index. This formulation thus resulted in an index that not only assesses security practices, but also gives the confidence that appropriate measures are in place.

NTI’s Nuclear Materials Security Index

The Nuclear Materials Security Index assesses each state across a broad range of publicly available indicators of a state’s nuclear materials security conditions. Specifically, the Index assesses states across 18 indicators in five major categories. Indicators assessed which are relevant to transparency include the following.

Quantities and Sites

- Quantities of weapons-usable nuclear material held

- Are these quantities decreasing or increasing?

- The number of sites involved

- Frequency of nuclear materials transport

Security and Control Measures

- Are there mandatory security requirements?

- Does the state undertake on-site security reviews?

- Does the state apply a Design Basis threat?

- Are security responsibilities and accountabilities clearly delineated?

- Does the state apply a performance-based nuclear security program?

- Is there a requirement for vetting security personnel and demonstrating performance of security systems and procedures?

- What is known of the state’s security response capabilities and training?

Global Norms

- Which nuclear security-related regimes has the state joined?

- What international commitments has the state made?

- Does the state participate in bilateral or multilateral assistance programs?

- Does the state invite external review?

Domestic Commitments and Capacity

- Does the state’s domestic legislation meet the requirements of the international regimes?

- Is there an independent regulator for nuclear security?

The Index considered transparency specifically as one of the indicators in the Global Norms category, with the view that appropriate degrees of transparency are important for a state to provide confidence to others that appropriate security measures were in place. To assess transparency, the Index considered whether a state has publicly released the broad outlines of its security arrangements, has made any public declaration regarding its quantities of nuclear materials, and has requested an international review of its security arrangements. States exhibited a wide range of scores for transparency when assessed in this manner.

It can be seen that the information covered by these indicators is not of a kind that would compromise security of nuclear material and facilities. The information used in the Index was drawn from open sources. However, availability of such information varied considerably from one state to the next. An important objective of transparency is for all states to make available a similar range of information.

The only specific area of information where some states have expressed concern is with respect to nuclear material quantities. Some states consider that to declare their inventories of weapons-usable nuclear material could compromise their national security, or the physical security of the material. NTI is proposing an aggregate declaration by each state, certainly not a declaration of site-specific inventories. It is debatable how sensitive aggregate information on nuclear material inventories really is, given that the major nuclear-weapon states have been declaring military as well as civil stocks for some years, and authoritative estimates are published for all the nuclear-armed states. [5] For future accountability and to track progress around the world over time, it is critical that states provide official and accurate inventory declarations of weapons-usable nuclear materials.

Examples of Transparency in Other Sensitive Areas

In nuclear security, the IAEA has carried out dozens of voluntary peer reviews under the IPPAS program, without any claims that security has been compromised by these reviews.

The closest parallel from another area is in nuclear safety. There is a significant overlap between safety and security – both disciplines are concerned, inter alia, with protection against the risk of radiation release resulting from acts of sabotage. Under the Convention on Nuclear Safety, peer review of national implementation arrangements has operated for some 15 years. WANO has operated a voluntary peer review process at the facility level for some 20 years (as mentioned earlier, this has now been made mandatory). The IAEA has operated the voluntary Operational Safety Review Team (OSART) program for some 30 years. At no time has it been claimed that any of these processes has resulted in compromise of security-sensitive information.

On 22 February 2012 WANO and WINS announced a collaborative effort to examine the interface between nuclear safety and nuclear security. A joint Working Group will be established with the objective of better defining and identifying best practices for managing the interface between these disciplines.

Another example of inter-governmental transparency is the sharing of national reports amongst the parties to the Chemical Weapons Convention. These reports, inter alia, list sites handling scheduled chemicals above specified quantity thresholds.

Transparency mechanisms are well established in arms control. Outside the nuclear and strategic fields, areas that might have been considered too sensitive for transparency and information-sharing, but where arrangements have been established and make an important contribution, include cyber security, financial transactions, aviation safety and aviation security.

Conclusions

Appropriate transparency and accountability mechanisms are an essential part of the state’s ability to assess its own nuclear security performance, and to gain assistance and support where this is needed. Such mechanisms are also essential to provide the international community with assurance that the state is meeting international obligations and expectations.

For those states unhappy with the NTI Index there is a simple answer – they can take a constructive approach and develop their own proposals for optimum transparency and accountability arrangements. NTI welcomes the views of others on appropriate transparency indicators that would provide assurances without compromising security.

It is time for the nuclear security community to learn from their nuclear safety colleagues. Developing reporting and other transparency and accountability mechanisms is an essential part of international cooperation to ensure high security standards and to reduce the risk of weapons-usable nuclear materials falling into the wrong hands.

Q&A with John Carlson

What is transparency?

Transparency is an important concept in international security. It is used to describe various forms of openness that enhance public and international confidence and understanding. It can also minimize misperceptions and increase accountability.

What do we want to be transparent?

States should be transparent about a range of national-level actions that demonstrate a commitment to having robust nuclear security measures in place. Examples would include publishing:

- Information on the overall framework for ensuring materials security

- National-level regulations for facilities and people dealing with nuclear materials

- Overall quantities and numbers of sites with nuclear materials.

What should not be transparent?

Information should not be made available if it could compromise the security of nuclear material and facilities, e.g. information useful in the planning or conduct of a malevolent act. Such information would typically be site-specific information such as the specific locations of materials or details of physical protection arrangements.

Why is transparency important?

States must work together to build a system for tracking, protecting and managing nuclear materials in a way that builds confidence that each state is meeting its security responsibilities. Transparency is a necessary part of accountability and demonstrating that a state is taking its security responsibilities seriously. Accountability helps ensure that states meet their international commitments, identify areas requiring improvement, and target international cooperation and assistance. Secrecy risks masking complacency and inadequate performance – leading to security vulnerabilities.

John Carlson was Australia’s Sherpa for the 2010 Nuclear Security Summit. More recently he was a member of the International Panel of Experts for the NTI Index.

Sources:

[1] While the international regimes in this area deal specifically with civil nuclear activities, there is an international expectation that nuclear material and nuclear facilities used for military purposes will also be accorded stringent physical protection.

[2] There are long-standing bilateral arrangements in the nuclear security area.

[3] World Institute for Nuclear Security.

[4] International Convention for the Suppression of Acts of Nuclear Terrorism.

[5] For example, the Global Fissile Material Reports published by the International Panel on Fissile Materials.

Stay Informed

Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest on nuclear and biological threats.

The 2023 NTI Nuclear Security Index

“The bottom line is that the countries and areas with the greatest responsibility for protecting the world from a catastrophic act of nuclear terrorism are derelict in their duty,” the 2023 NTI Index reports.

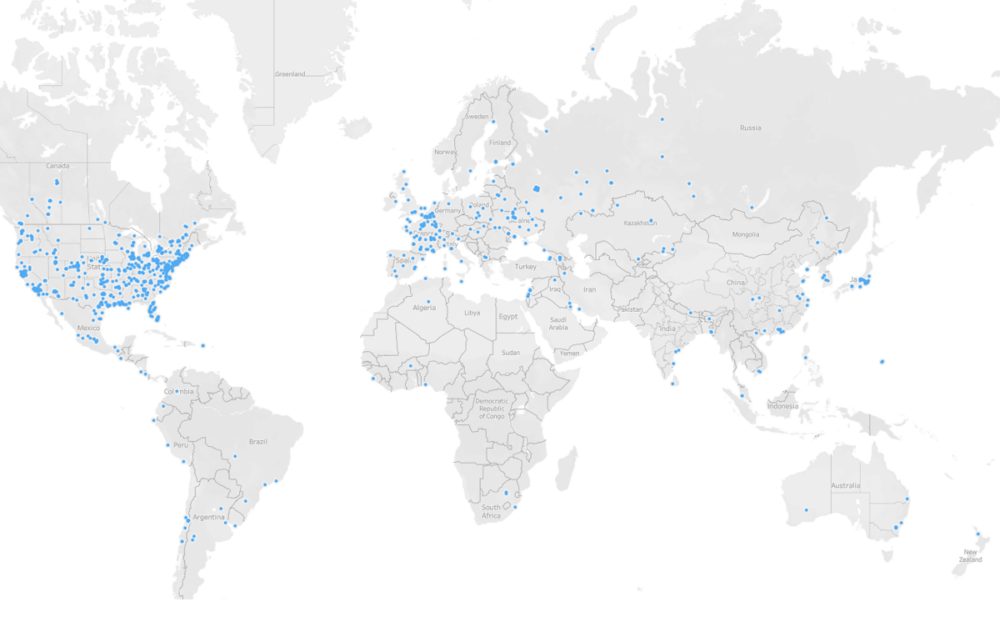

Overview of The CNS Global Incidents and Trafficking Database

The only public database of its kind, includes global nuclear & radiological security trends, findings, policy recommendations, and interactive visualizations.

CNS Global Incidents and Trafficking Database Archived Reports and Graphics

Archives of Global Incidents and Trafficking Database, 2013-2018. (CNS)