Atomic Pulse

Get to Know NTI: Page Stoutland

Page

Stoutland is NTI’s Vice President for Scientific and Technical Affairs. He focuses

on strengthening cybersecurity for nuclear weapons systems and at nuclear

facilities and addressing the impact of new and emerging technologies on NTI’s

mission. Prior to joining NTI, Stoutland spent 10 years at Lawrence

Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) where he held a number of senior positions

and was instrumental in developing and leading LLNL’s programs in support of

the post-9/11 homeland security effort. He holds a bachelor’s degree from St.

Olaf College in Northfield, Minnesota and a doctorate in chemistry from the

University of California, Berkeley. Page sat down with NTI’s Caitlyn

Collett for the latest in Atomic Pulse’s “Get to Know NTI”

series.

Before joining NTI,

you worked at several national laboratories. What was your favorite project

while working in labs?

I think some of the more interesting projects were when I

first started at Los Alamos National Laboratory at the beginning of my career.

We built an apparatus that was able to do what’s called picosecond infrared

spectroscopy – meaning we were able to measure very short timeframe reaction

dynamics.

We applied that to some biological molecules of interest, as

well as to understand fast reaction dynamics in polymer films that was of relevance

to imaging technology – sort of next-generation laser printers. The combination of building the apparatus and

the actual technical work was fun and interesting and something that I

certainly missed as I moved onto other assignments.

What inspired you to

move from that kind of research work to policy?

When I was at Los Alamos, I was doing some basic science, but

it was evident to me that at a national laboratory the main focus was national

security work. Because I’m a chemist, I became interested in how we might

address chemical and biological issues in the realm of national security.

I had the opportunity to come back to Washington to assist

in a newly formed program that was working to develop chemical and biological

defense technologies. It was a one-year assignment that turned into a four-year

assignment, and that was my introduction to the Washington world and policy.

You must have

discussed a lot of important issues during those assignments. What do you think

is the greatest threat facing the world today?

I’m very concerned about cyber threats that can affect

infrastructure as well as nuclear facilities. That’s certainly something we

think about here at NTI.

In addition, I’m increasingly concerned about how information

can manipulate public opinion, whether it be through cyberattacks or

information attacks, as we’ve seen in the most recent election. I think that’s

a very concerning development and I don’t know how we’re ever going to completely

solve that problem. I think the spread of information technology and malevolent

uses of such technology is really concerning looking forward.

What do you think

that people can do as individuals to kind of like mitigate that threat?

Yes, I don’t know other than —

Staying off Facebook?

Yes. I think we have to get back to thinking about how facts

matter and considering the reputation of the media outlets that we receive our

information from. Whether it’s The New

York Times or elsewhere, readers should be curious about whether an outlet has

a history of good journalism, how their people are curating and documenting it,

and what journalists are referencing. Maybe there we can get some traction.

Of course people who are seeking good journalism

may not be the people we need to worry about. It’s the population overall, and

you only have to shift some small fraction of them to make a big difference.

Knowing that something is true is actually incredibly difficult,

because we all have very limited experiences. We typically don’t automatically

believe something is true, but rather because somebody we trust has told us

it’s true.

So, it’s a very difficult problem. Hopefully you’ve got some

ideas.

I’ll start

brainstorming right away. Can you tell

me a bit about what you’re working on NTI?

We’re working on the implications of new technology on

catastrophic threats. I think the implications can be both positive and

negative. I think it’s clear that the cyber threat is making addressing nuclear

weapons issues even more difficult. Cyber threats are very destabilizing and can

lead to miscalculated use of nuclear weapons. So we spend a lot of time

focusing on how to mitigate that risk.

Maybe on the more positive side, we started a new project

that will use large quantities of publically available data to monitor and

maybe even verify agreements having to do with proliferation. Contrary to what

I discussed earlier, the fact that we’ve got all this public data has a lot of

potential, and we’re trying to figure out how to demonstrate that and how to

use that for positive purposes.

The world definitely

has a lot to learn on these issues. I heard you briefly taught a course at

George Washington University on the “Science of Nuclear Materials,” which was

actually my favorite course when I was in grad school there. What did you learn

from your time teaching?

I learned that students are really smart, incredibly hardworking,

and are really trying to make a difference. It was great to see young people

with the optimism one tends to lose as we get older. It was really gratifying.

I think it’s always gratifying to share one’s experiences

with others. So for that particular class, which was about technology issues

and nuclear issues, since I’d done a fair bit of technical work and policy work

in my career, and it was nice to be able to bring those together in that

class.

Do you have any

advice for those young people as they continue their studies and careers?

I do. I think it’s

important for young people to go out and get what I call “real jobs.” By that I

mean something that’s got real deadlines, maybe even delivering something to a

sponsor, and if you’re scientist, doing scientific work. Something that’s hands on and you can sink your

teeth into.

The flipside of that is that a lot of young people want to

get out and do policy work of some sort. Policy development requires not only

knowledge about the issue, but a certain experience base and you don’t

typically have that experience base when you’re in your early 20s. So, I really

think it’s important to go out and do something, develop skills and then maybe

come back to the policy space at some later time.

I could see why it

would be hard to jump in to making a change, when you haven’t yet seen what

needs to be changed.

Yes, it really is. Plus, it is difficult to have your voice

heard as a new-to-the-industry 23-year-old, even if you have great ideas. It

could be the same idea coming out of your mouth that somebody who has been in

the business for 30 years. But if you’ve been in the business for 30 years,

you’ve got enough gravitas that people will listen.

Hopefully the

incoming generation of policymakers will read your advice. My next question is

sort of “out of left field.” What would be your first question after waking up

from being cryogenically frozen for 100 years? What would you be most curious

about what’s happening in the world?

I would wonder what my kids were doing. I would want to know

how they turned out.

I think that’s a fair

first question. What do your kids do now?

So, I have four. I have three older kids, and a younger one. My oldest daughter is working in Doha at the Brookings

Institution, and my older sons are fourth-years in college at the University of

Chicago and Pomona College. My youngest daughter is two-and-a-half and is

enjoying life like two-and-a-half year olds do.

Sounds like they’re

all thriving. My next question is, aside from your work at NTI, what could you

give a 40 minute presentation on with absolutely no preparation?

I could give a 40 minute presentation on cross-country skiing.

Really? That’s so

unique! Do you cross-country ski often? Where do you usually ski?

Yes! We ski all over the country. We just got back

from a training camp in West Yellowstone, Montana. And we ski up in Northern

Michigan, Vermont, New York, Pennsylvania.

My favorite is probably West Yellowstone because it’s spectacularly

beautiful and it has one of the best trail groomers in the country. The skiing

is always perfect there.

How did you get

started? That’s not a common hobby.

I got into it when I went to college in Minnesota. In

Minnesota in the winter, there’s not much to do other than ski. So, we started

skiing and ski racing and I’ve just sort of been obsessed with it ever since.

The frequency of my skiing depends on the year, but one year I skied everyday

between Thanksgiving and April.

I love being outside all year round, but winter is so

magical. That’s my complaint about Washington, we don’t have good enough

winters.

It’s wonderful that

you get to travel so much to ski, but what’s your favorite place you’ve

travelled for work?

For work, favorite place? I’ve been to a lot of places, but it’s

hard to beat Scandinavia. I mean, of course I’m of Norwegian heritage myself,

so maybe it’s like going back to my youth or something. But, I mean, Stockholm

and Oslo are great cities.

What do you like

about Oslo?

It’s on the water and it’s so beautiful. The food and the

people are just great. It’s a very diverse city, and it’s easy to get around

practically. So, it’s comfortable. That said, I’ve had great experiences in

many cities. Minsk I found to be interesting. Places in China, I’ve been have been quite interesting.

Everyone loves Vienna, but to be honest it doesn’t do much for me. I was in

Toronto recently. Toronto is a great city.

I feel like Canada is

underrated.

Canada is underrated. Canadian wine is underrated. I had

never had Canadian wine until this trip to Toronto. I said, “All right,

I’m going to drink Canadian wine.” It was amazing. The grapes are grown up

by Nigeria Falls.

Wow, I wouldn’t have

expected that either. My final question is what is one item you couldn’t live

without?

One item can’t live without. This is fascinating – there’s

probably nothing. Because I’m pretty adaptable, but what could I not live

without? So the – it’s like what things do I have that I really could never see

myself getting rid off, other than my kids. My bicycle comes to mind. That

would be hard to give up. My heart rate monitor, I kind of like that, but I

could probably give that up. What else do I have? I have so many skis, I could

give up any one of them and it wouldn’t be a problem. I’m very minimalistic in

a sense.

That’s very

Scandinavian of you.

I suppose that’s true. What I really care about are some of

my toys. So, my bicycle, my motorcycle, my skis. It’s not like I couldn’t live

without my phone.

I feel like that

would be a common answer. I think that in reality I probably couldn’t live

without my phone.

Right, but you don’t want to admit that.

Stay Informed

Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest on nuclear and biological threats.

More on Atomic Pulse

Deep Fakes and Dead Hands: Artificial Intelligence’s Impact on Strategic Risk

Artificial Intelligence has many potential applications and consequences for strategic risk. Here is NTI’s work on it so far.

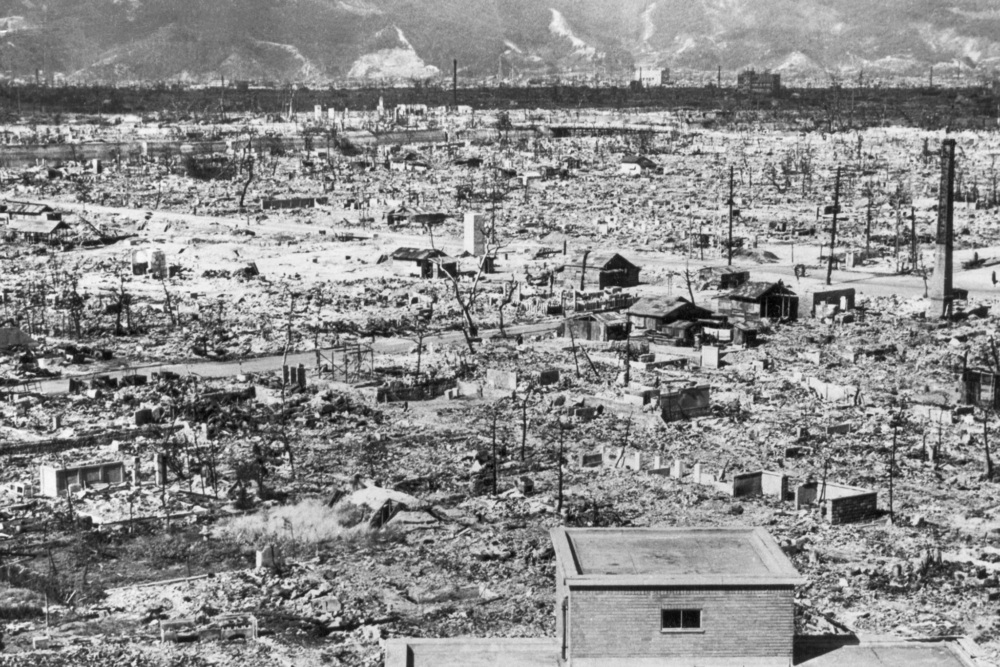

Depicting Nuclear Risk Accurately: The Likely Global Effects of Nuclear Weapons in the 21st Century

The bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 made clear the destructive force of the light, heat, blast, and radiation from a nuclear explosion. But what exactly would the effects of a nuclear explosion mean for the world today?

NTI Seminar: Chris Painter on Avoiding Nuclear Escalation from Cyberattacks

What happens “if we can’t rely on the information we have,” asks Christopher Painter, former top U.S. cyber diplomat. In an NTI seminar on January 25, Painter posed this critical question and discussed a range of issues at the intersection of cyber and nuclear security.