Mimi Hall

Vice President, Communications

Atomic Pulse

Ray

Rothrock is a member of NTI’s Board of Directors and its

Science and Technology Advisory Group. He has

three decades of business leadership—investing in, advising and leading many of

the technology and cybersecurity companies that form the fabric of today’s

networks. He is partner emeritus at Venrock, the VC arm of the

Rockefeller family’s efforts, and the CEO and chairman of RedSeal, which

provides critical cyber and business insights via its cyber risk modeling

platform to more than 50 government agencies and hundreds of commercial

enterprises. Rothrock holds a BS in Nuclear Engineering

from Texas A&M University, a MS in Nuclear Engineering from the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and a MBA with Distinction from the

Harvard Business School. He is author of Digital

Resilience: Is Your Company Ready for the Next Cyber Threat?

You’re probably best known, at least recently,

as an expert on cybercrime and cyber security, right? But you also have a

background in nuclear engineering. So, you could have spent your career in a

nuclear sub under the sea.

Not

quite. It turns out that I’m color blind

enough that Admiral Rickover wouldn’t have me in his fleet.

Oh, wow.

So, I went

the civilian route. And I did spend five years in the industry and a year and a

half at a (nuclear) plant. Yankee Rowe in Massachusetts. It was back in the

late ’70s.

So the combination of your backgrounds

in cyber security and nuclear engineering, I assume, is what led you to NTI?

Yes, I mean,

I was a nuclear engineer for five years. I actually got my professional certification. The Three Mile Island (the accident involving

the partial meltdown of a reactor and radiation release at a nuclear plant in

Pennsylvania in 1979) had its impact on the nuclear power industry, which

looked like it was hunkering down. So, just

as the nuclear industry took this not-quite-fatal hit, the PC was born and the

Apple II computer came on the market. I bought one of those silly little

things. I say silly little thing, but it

had a massive impact on our world.

And then I

moved to the Silicon Valley and landed there in 1981 when the whole Silicon

Valley thing was just starting to happen. So, I made a very conscious decision

to get involved in this emerging personal computer industry, while somehow

keeping the bills paid with nuclear engineering consulting and what have you.

How did that go?

I did three

start-up companies. The first two were nuclear

engineering software companies, and they ultimately failed, one very

dramatically, and I finally landed at a new company called Sun Microsystems,

which was venture backed. So it was at

Sun, I was introduced to venture capital (VC).

After success at Sun, I went to business school

intended to get into VC. In those days, that was the union card, so to speak,

that you had to punch to get into VC, it was a very small industry. So, I went to Harvard, and I took a position at Venrock. I was there for 25 years.

At Venrock I invested

in infrastructure for hard things, hard technical things, and I taught myself a

lot about computers, networking, and all the infrastructure. … And one of the

concepts that I was taught as a young associate at Venrock was, you want to

look for opportunities that aren’t just one-off opportunities but in fact lead

to subsequent opportunities and that’s what the Internet turned into, right?

So I became

quite interested in cyber security and cyber threats.

How so?

As the Internet

happened, as companies connected into the Internet, bad guys appeared on the

scene and new threats appeared. I managed

to get connected with the entrepreneurs who ultimately created the leading company

to address that new threat with a firewall technology. Eventually, there were, I don’t know, there

were probably 10 of us in Silicon Valley who did all of the cyber deals. … And

we’re still doing them and we’re still killing it because the threats are never

ending.

In 2013, I retired

from Venrock—and I thought I was really going to retire. But then one of the

cyber deals that I invested in got itself in trouble. I was a big believer in it, so I was asked to

become the CEO and hoped to kind of, you know, as we used to say the venture

business, clean it up, knock out the dents, put a fresh coat of paint on it,

and maybe find a home for it. But instead what I found was some incredible technology

that could address what I saw as a new emerging threat. This new threat was exhibited by the Target

attack—the Target Corporation attack in 2013.

We all remember that one.

Right. So here’s

a great company—Target, a Fortune 50, lots of software, lots of engineers,

sufficient budget—and it got hacked and hacked bad. Why? Every good engineer would ask, why? Why did that company get hacked? And come to find out, the bad stuff, the

malware was inside the network, not an attack from the outside. And as I began to investigate, Sony, JPMorgan,

Home Depot, the U.S. government, just suddenly the whole world was being

attacked in similar ways, and it’s all front page news.

So that

inspired me to think about that problem and how it got in. And if you assume it’s in, what do you do

about it? Firewalls aren’t going to keep

everything out anymore, data leak isn’t keeping it in, all this stuff that was

about prevention and detection worked to a degree, but it wasn’t perfect. So,

this concept of digital resilience crept into my head after reading a bunch of

books by McKinsey and Rodin. So I decided

to write a book about this idea, it’s called Digital Resilience, and I think that’s what really cemented my

cyber expertise if you will.

How did you end up working with NTI?

I’ve known (NTI

Co-Chair and CEO) Secretary Moniz for many years as I’m on the board of MIT

among connections. He of course finishes

his tour as Energy Secretary and lands here at NTI. As cyber became an issue related to NTI’s

mission, Ernie gave me a call and said, “Hey, would you consider coming

and help us here and think about how to frame cyber in the context of nuclear

weapons?” And how can you say no to Ernie?

Can you talk a little bit about how

serious and urgent a concern cyber threats are to our nuclear infrastructure, both

nuclear facilities and weapons command and control? I mean, attacks on Target and other

businesses are not trivial. They can

impact global economies. But nuclear—that’s a whole different ballgame.

There’s no

question, it’s a very serious and urgent matter. Nothing is perfect, and if a hacker really

wants in, they will figure out how to get in to do something. My dad taught me as a little boy, locks keep

honest people honest. The harder the lock, the more intrusion it will prevent. But every lock is breakable …

Do I think

someone wants to launch a weapon or detonate a weapon in silo or something like

that? No, I don’t think that’s the state

of play and besides that’s probably very hard to do. What I do think the state of play is to

weaken the trust that we have in our systems that manage and control not just

the weapons, but the decision framework for use. And if we weaken the trust and then create a

threat, do the people believe the threat is contained? It’s more about the terror concept of it more

than the actual physical event of it.

You could use

cyber to create an incredible deception. NORAD’s (North American Aerospace

Defense Command) had several false flags in its history. You know the movie WarGames with Matthew Broderick? Think about when that came out (in

1983), and I was like, that could happen tomorrow. There also is a great, a fictional book

called Ghost Fleet in which there is an

attack on the United States by China in 2024 or something like that. Before the attack they used cyber to disable

our defensive systems so that a kinetic attack would work preventing or

blunting a U.S. response. The Ghost

Fleet refers to all of the old weaponry airplanes and ships that are not

dependent on computers and that is what the US grabs and use. We bring those

out to defend against the Chinese.

So, given your perspective on where

the real threat lies, can you talk a little bit about what you think our

government and governments should be doing and what kind of role you think NGOs

can play? What kind of a role can NTI

play to address this threat?

Well, I think

a key thing to addressing the threat is to share what those threats are—and NTI

is right in the middle of this conversation. It’s about transparency and data sharing. During the Obama Administration, I was

involved in the writing of several bills originating in the Senate that tried

to come up with data-sharing plans and policies. None of it ever got off the ground because

the commercial sector doesn’t trust the government to keep the data safe, and lo

and behold, they were right. The government can’t keep it safe. So, there are

serious questions about who owns the data and who’s got the keys. It’s a real

standoff, but we’re going to have to have a policy of data sharing and threat

sharing and ultimately response sharing.

Transparency is key.

Before you go, can I ask you a little

bit about what you do in your spare time, if you have any, when you’re not

worrying about trying to address these kinds of threats?

Well, music

certainly is something I do. I became a

musician beginning in the 4th grade. I

learned to play the clarinet, and I played woodwinds all the way through

college and then got busy with life. And then along came my son in 1990. He went to Middlebury and got a music and theater

degree. And when he finished college, he moved back to California to go professional

theater. We formed a rock band, Up and to

the Right. He is the lead singer and I’m

the bass player.

He lives in

New York now, but when we have a gig, he flies out. He’ll show up the night

before, we’ll have a rehearsal, and he, I mean, he can walk on the stage and

just kill it.

The band is called Up and to the

Right. What does the name mean? Where

did that name come from?

Oh, I’m so

glad you asked! So, at Venrock, I spent 10 years in New York City. Wall Street has its own vocabulary, and I

learned a lot of that vocabulary. So, if

you think about financial graphs, time is on the X-axis and other things are on

the Y-axis, stock price, profits, revenue, market share, etc., and a good graph

is one that’s going up and to the right because that means things are getting

better.

And so, when

I moved to California, I sort of showed up in the venture capital role there

with a lot of New York-Wall Street slang, and people didn’t know what “up and

to the right” was, and I used it a lot. So

that’s the source. It was very catchy, and so when the band formed, we used Up and

to the Right.

I bet you have a lot of fun with the

band. That’s like a father’s dream, I think, to get to play in a band with your

son.

It is. You

know, one of my mentors told me, he said, you know, when you have children

someday, you’ll try to force them into things you like. Think about it, flip it around. Do what they like, and you’ll have a better

relationship. That mentor was right.

That’s fantastic.

The other

thing I do is emergency preparedness in my town. I’m the ham radio guy, I have

been for 45 years. And I’m an engineer, so I’m actually quite good with my

hands, and I can fix things and stuff. So,

I run the communications network that we have in town. I’ve been doing it for

20 years this month, and with all the power outages we had lately, all the

preparation has paid off in spades.

That’s very rewarding, right? At the

local level you can really see the results of your efforts. That’s cool.

Yeah. And we

also put up a broadcast, radio station.

It’s just putting out emergency information, and so we got a call from

the town manager yesterday before I flew out here (to the NTI Board meeting). He says, this is great – what else can we

do? So, you know, I get to spend the

taxpayers’ money to serve them.

And then – from small-town

preparedness, you fly to Washington and talk about nuclear threats.

Right! So that’s

what I do for fun. And then, of course, my wife Meredith and I, we play golf

and travel a bit. I have a great family.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest on nuclear and biological threats.

Artificial Intelligence has many potential applications and consequences for strategic risk. Here is NTI’s work on it so far.

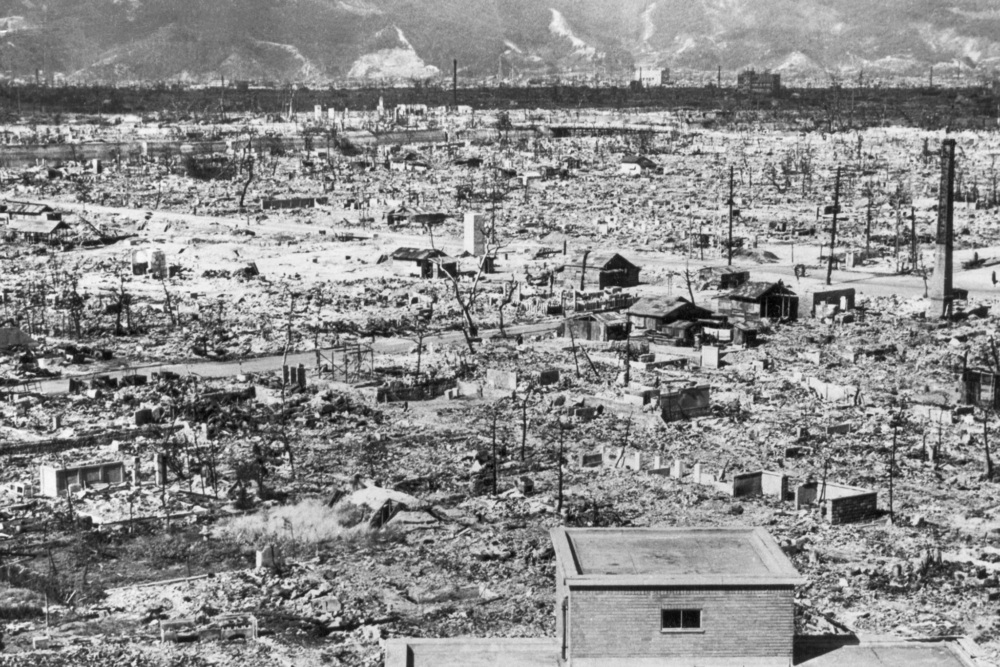

The bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 made clear the destructive force of the light, heat, blast, and radiation from a nuclear explosion. But what exactly would the effects of a nuclear explosion mean for the world today?

What happens “if we can’t rely on the information we have,” asks Christopher Painter, former top U.S. cyber diplomat. In an NTI seminar on January 25, Painter posed this critical question and discussed a range of issues at the intersection of cyber and nuclear security.