Elena Sokova

Executive Director, Vienna Center for Disarmament and Non-Proliferation, The James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies

With the Cold War behind them, the United States and Russia pledged to eliminate excess weapons-grade plutonium in order to prevent theft or diversion for illegal nuclear programs. Both states also wanted to ensure neither was able to reincorporate this material into its weapons arsenal. In 1998 the United States and Russia each declared 50 metric tons (mt) of plutonium to be surplus to their security needs and this was followed by the September 2000 Plutonium Management and Disposition Agreement (PMDA) in which both countries agreed to transform 34mt of excess military plutonium into a proliferation-resistant form. In order to achieve this target, Russia intends to irradiate all 34mt of its plutonium in fast-neutron reactors, thereby utilizing the mixed-oxide (MOX) fuel option. The United States originally planned a dual-track approach in which it would irradiate the majority of its surplus plutonium as MOX fuel, as well as immobilizing a smaller quantity with highly radioactive waste. However, in early 2002, due to steep increases in the cost of the U.S. disposition program, the administration announced its decision to concentrate solely on the MOX option and cancel the immobilization track.

The PMDA was stalled for almost 10 years as both countries faced practical difficulties in implementing the agreement. Start-up costs for plutonium disposition are extremely high and neither party had industrial-scale MOX fuel production facilities. However, a fabrication plant is now being constructed at Savannah River in the United States and one is planned for Zheleznogorsk in Russia.[1] Modifications are also being made to the Russian BN-600 fast reactor to increase its efficiency and meet plutonium disposition goals. Washington has pledged $400 million to help Moscow establish its disposition program and both countries hope to secure additional international funding. It is estimated that plutonium disposition will begin in 2018 after the completion of the MOX fuel fabrication facility at Savannah River, which is likely to begin operating around 2016.[2] Russia, however, may begin plutonium disposition at an earlier date, should it be in a position to do so.[3] Once MOX irradiation begins, it is estimated that it will take around 20-25 years to dispose of the 34mt stipulated in the agreement.[4]

During the Cold War, the United States produced approximately 90mt of weapons-grade plutonium and the Soviet Union between 120 and 165mt.[5] Nuclear arms reduction efforts in the late 1980s and 1990s slated thousands of nuclear weapons in the United States and Russia for dismantling and elimination. These nuclear weapon reductions, with their indisputable benefits for global security, meant the two countries no longer required large stocks of weapons-usable materials for their arsenals and that existing stocks would increase further as nuclear materials were removed from warheads.

In 1995, the United States announced that it possessed more than 50mt of plutonium in excess of national security needs; in 1997, Russia followed suit and declared 50mt of weapons-grade plutonium surplus to its defense program. Both countries pledged to take steps to ensure this material would never again be used for weapons or fall into the wrong hands.

Producing or acquiring fissile material is the biggest obstacle for any state or non-state actor that seeks to build a nuclear weapon. Therefore, eliminating surplus military plutonium will reduce the risk of it being stolen or diverted to illegal nuclear programs. It also ensures that neither the United States nor Russia will reincorporate the material into its nuclear weapons program.

Unlike weapons-grade uranium, which can be rendered unusable for nuclear weapons by blending it with lower-grade uranium (a blend that can then be used as fuel in nuclear power plants), plutonium cannot be blended with other materials or diluted to make it unusable in weapons. However, steps can be taken to greatly complicate the use of plutonium for nuclear arms. Spent nuclear fuel for commercial power reactors, for example, contains roughly 1% plutonium, but is bound up with highly radioactive material, therefore creating a high-radiation barrier. In addition, the process of separating plutonium and uranium from spent fuel is technically difficult and expensive. Consequently, plutonium in spent fuel is considered to have relatively modest proliferation risk. For the disposition of weapons-grade plutonium, specialists have sought to devise methods based on these properties of spent fuel to make weapons-grade plutonium inaccessible for weapons use, a goal commonly known as the "spent fuel standard." (For details, see Management and Disposition of Excess Weapons Plutonium by the National Academy of Sciences.)

During the early 1990s, U.S. and Russian technical and government committees considered several plutonium disposition options. In the end, two options were identified as meeting the two states' nonproliferation objectives: (1) irradiating plutonium as nuclear power reactor fuel; and (2) immobilizing it with high-level radioactive waste in an inert matrix (such as glass or ceramic), and then disposing of the material in a geologic repository.

The irradiation option involves the production of mixed-oxide fuel, or MOX fuel, consisting of both plutonium and uranium oxides, which is then burned in U.S. and Russian nuclear power reactors. Moscow considers plutonium a valuable energy source and insists on using its surplus plutonium as fuel rather than immobilizing it. Moreover, because irradiation of MOX in nuclear power plants transforms weapons-grade plutonium into lesser quality "reactor grade" plutonium (while immobilized plutonium remains weapons-grade), Russia insisted that the United States adopt the MOX option for the bulk of its surplus plutonium. Russia argued that if the United States merely immobilized its surplus plutonium, it might some day re-separate the weapons-grade material and reuse it for nuclear arms.

On September 1, 2000, the United States and Russia signed the Plutonium Management and Disposition Agreement (PMDA). It stated that both countries must dispose of at least 34mt of weapons-grade plutonium at a rate of 2mt per year. Although the United States originally planned to dispose of 25.5mt as MOX, and to immobilize 8.5mt for storage in a geological depository, Washington has since revised this plan and will now irradiate all of its material as MOX fuel. Russia will also utilize the MOX method to dispose of its 34 metric tons. The 2000 agreement stated that both countries would irradiate the fuel in light-water reactors but Russia retained the option of using its BN-600 fast-reactor at Beloyarsk.

However, implementation of the agreement was delayed, partly because of Russia's reluctance to devote significant resources to a program that would be based on light-water reactor technology. In order to solve this problem, both parties agreed in 2007 that Russia would instead use fast-neutron reactors, including its existing BN-600 reactor at Beloyarsk and a more advanced BN-800 reactor that will be constructed at the same location. The protocol to the PMDA — signed in April 2010 at the Washington Nuclear Security Summit – will make the Russian disposition method compatible with the country's long-term nuclear energy strategy and therefore more financially viable.[6] Furthermore, the 2010 protocol also included a revised disposition rate of no less than 1.3mt per year, which more accurately reflects the combined disposition capacity of the two fast-neutron reactors at Beloyarsk.

Critics of the fast-reactor option have highlighted the potential for these reactors to produce more plutonium than they irradiate. To address these concerns, the 2010 protocol stated that "the BN-800 will be operated with a breeding ratio of less than one for the entire term" of the agreement.[7] In addition, the radial blanket of the BN-600 reactor would be "completely removed" to ensure the reactor was operating in "burner" and not "breeder" mode. The agreement also bans each party from separating plutonium from irradiated MOX fuel ("reprocessing") until that party has disposed of all 34 metric tons of plutonium subject to the agreement. Any additional plutonium designated in the future by either country as excess to defense needs can be disposed of under the terms and conditions of the September 2000 agreement and the 2010 protocol.

Although there were significant obstacles to the PMDA's implementation in the ten years that followed the 2000 agreement, the 2010 protocol appears to have addressed some of these challenges. Both country's respective programs are still at an early stage and disposition cannot begin until the necessary infrastructure is in place. For the MOX fuel option, this involves the construction of facilities for plutonium conversion, MOX fuel fabrication, and storage. Existing nuclear power reactors must also be modified to burn MOX.

Projected costs for the program have significantly increased since 2000, with estimates now as high as $3 billion for the Russian program and $4-5 billion for the U.S. program.[8] The United States will also provide $400 million in financial aid to facilitate the implementation of the Russian program, with a large proportion of this sum going towards the construction of a MOX fuel fabrication plant in Russia. However, the 2010 protocol states that while up to $300 million of this can be spent on development and construction activities, no less than $100 million should be spent after disposition actually begins, at which point expenditure will be allocated at a fixed rate per metric ton of disposition.[9]

Opponents of the MOX burning option assert that immobilization of plutonium is safer, faster, and cheaper. They also argue that channeling weapons-grade plutonium into the civilian nuclear fuel cycle would increase, rather than decrease, the risk of diversion of the material. In addition, burning MOX fuel in reactors would reduce – but not completely eliminate – military plutonium in the resulting spent fuel. Therefore, after years of "cooling" the irradiated fuel elements, the two countries would have to decide what to do with the spent fuel, which would still contain plutonium, although in smaller quantities than is found in fresh MOX fuel. The United States plans to dispose of its spent MOX fuel along with conventional spent fuel from nuclear power plants. Russia's plans are uncertain, but it has reserved the right to reprocess its spent MOX fuel once all 34mt of plutonium is irradiated – that is, to separate plutonium from the spent MOX fuel for reuse in "second generation" MOX fuel for nuclear power plants.

When the Bush administration came to office in January 2001, it ordered a review of all nonproliferation programs with Russia, including the plutonium disposition program. The administration questioned the feasibility and nonproliferation value of plutonium disposition due to its high costs and implementation uncertainties. In the end, the National Security Council review, which was completed in December 2001, recommended that the plutonium disposition program be continued but emphasized the need for lower costs and increased efficiency. It was partly because of this requirement that the United States announced in January 2002 that it would cancel the immobilization option and concentrate exclusively on the MOX fuel track. The Department of Energy (DOE) reported that cancelling the immobilization option would save the United States $2 billion in total program costs and accelerate closure of former nuclear weapons complex sites. As a result, the DOE is now proceeding with the construction of a MOX fuel complex at the Savannah River Site in South Carolina and began work on the Mixed Oxide Fuel Fabrication Facility (MFFF) in August 2007. Ground was also broken at the Savannah Waste Solidification Building in January 2009, which will process low-level and transuranic waste from the MFFF.[10] It is currently estimated that MOX fuel fabrication will begin at Savannah River in 2016. If, however, Russia is in a position to proceed at an earlier date, then it is entitled to do so as the 2010 protocol does not call for a strict linkage in the timing of the two programs.

The total cost of U.S. surplus plutonium disposition through the MOX option is anticipated to be around $4-5 billion over 20 years. The FY2010 appropriation for the U.S. plutonium disposition program was $665.1 million and the Obama Administration is seeking $891.7 million for FY2011.[11] Congress's appropriation for the disposition of Russian fissile material has also increased significantly as a result of the signing of the 2010 protocol to the PMDA. While the appropriation for FY2010 was $1 million, the budget request for FY2011 has increased to $113 million.[12] The 2010 protocol allows for the funds to be allocated to the development and construction of Russia's MOX fuel fabrication plant, as well as converting the BN-600 reactor so that it can run on MOX fuel. Although the funds cannot be used for the construction of the BN-800 reactor itself (this will be funded by Russia), they can contribute to the design of the reactor core.[13]

To ensure the plutonium subject to disposition is irreversibly removed from use in nuclear weapons, the September 2000 agreement specified the two sides would implement monitoring and inspection activities. The agreement also provides for International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) verification once appropriate agreements with the IAEA are concluded. These provisions were re-emphasized in the 2010 protocol, which states that each party will "begin consultations with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) at an early date and undertake all other necessary steps to conclude appropriate agreements with the IAEA to allow it to implement verification measures."[14] Nevertheless, much work on the establishment of a verification regime still needs to be done and this is unlikely to be completed before 2011, by which point the protocol should have entered into force.[15]

The 2010 protocol to the PMDA represents a significant step forward, but the agreement itself is limited in scope. Once the two countries have disposed of the required 34 metric tons, significant quantities will remain. The United States will continue to possess 16 tons of excess military plutonium in various waste and fuel forms, while Russia will retain at least 16 tons of weapons-grade plutonium declared excess to its defense program. These numbers are likely to increase once the two parties begin dismantling their nuclear arsenals under the 2010 START follow-on treaty. However, the United States and Russia can continue plutonium disposition beyond 34 metric tons should they wish to do so and the existence of an operational infrastructure for MOX fuel fabrication makes this possible.

[1] "Pod Krasnoyarskom v Zheleznogorske budut proizvodit novoe toplivo dlya AES," dela.ru, www.dela.ru, 31 August 2010.

[2] "Agreement between the United States of America and the Government of the Russian Federation concerning the management and disposition of plutonium designated as no longer required for defense purposes and related cooperation, as amended by the 2010 Protocol."

[3] Daniel Horner, "Russia, U.S. Sign Plutonium Disposition Pact," Arms Control Today, May 2010, www.armscontrol.org.

[4] Daniel Horner, "Russia, U.S. Sign Plutonium Disposition Pact," Arms Control Today, May 2010, www.armscontrol.org.

[5] David Albright, Frans Berkhout, William Walker, Plutonium and Highly Enriched Uranium 1996: World Inventories, Capabilities and Policies (New York: Oxford University Press Inc., 1997), pp. 40, 58.

[6] "2000 Plutonium Management and Disposition Agreement," Office of the Spokesman, U.S. Department of State, www.state.gov, 13 April 2010.

[7] "Agreement between the United States of America and the Government of the Russian Federation concerning the management and disposition of plutonium designated as no longer required for defense purposes and related cooperation, as amended by the 2010 Protocol."

[8] "Disposal of weapons-grade plutonium to cost Russia up to $3 bln," RIA Novosti, 15 April 2010, www.rian.ru.

[9] Daniel Horner, "Russia, U.S. Sign Plutonium Disposition Pact," Arms Control Today, May 2010, www.armscontrol.org.

[10] "Ground Broken for Second Facility in Plutonium Disposition Complex," Savannah River Site, www.srs.gov, 16 January 2009.

[11] "U.S. Plutonium Disposition Budget," Nuclear Threat Initiative Research Library (Securing the Bomb), www.nti.org.

[12] Matthew Bunn, "Securing the Bomb 2010," The Nuclear Threat Initiative, www.nti.org, April 2010.

[13] "Agreement between the United States of America and the Government of the Russian Federation concerning the management and disposition of plutonium designated as no longer required for defense purposes and related cooperation, as amended by the 2010 Protocol."

[14] "Agreement between the United States of America and the Government of the Russian Federation concerning the management and disposition of plutonium designated as no longer required for defense purposes and related cooperation, as amended by the 2010 Protocol."

[15] Daniel Horner, "Russia, U.S. Sign Plutonium Disposition Pact," Arms Control Today, May 2010, www.armscontrol.org.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest on nuclear and biological threats.

“The bottom line is that the countries and areas with the greatest responsibility for protecting the world from a catastrophic act of nuclear terrorism are derelict in their duty,” the 2023 NTI Index reports.

Understanding nuclear materials, including how plutonium and enriched uranium are produced, and the basics of nuclear energy and nuclear weapons, is the focus of this tutorial.

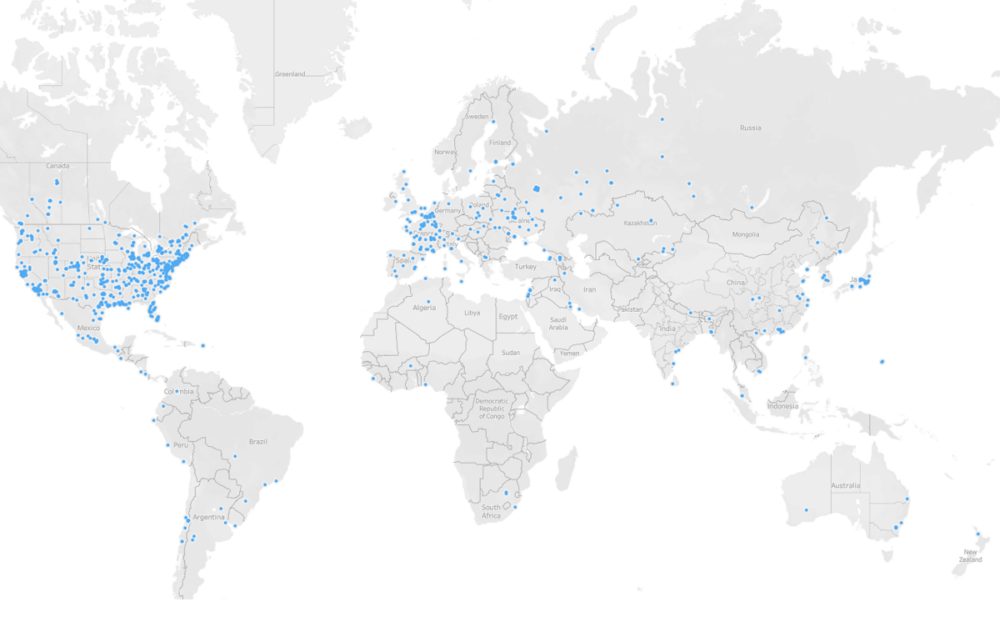

The only public database of its kind, includes global nuclear & radiological security trends, findings, policy recommendations, and interactive visualizations.