Cristina Chuen

Senior Research Associate, The James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies

Although "dirty bombs," or radioactive dispersal devices (RDDs), are not weapons of mass destruction, in the past few years terrorists have indicated their interest in acquiring such weapons. RDDs disperse highly radioactive material by using conventional explosives or other means. There are only a few radioactive sources that can be used effectively in an RDD. The greatest security risk is posed by Cobalt-60, Cesium-137, Iridium-192, Strontium-90, Americium-241, Californium-252, and Plutonium-238.

In Russia, the radioisotope thermoelectric generators using Strontium-90 that power lighthouses are a particularly acute problem, and have even been stolen by children. The number of orphaned sources (lost, abandoned or stolen radiological sources) in Russia has diminished in the past several years, but remains an issue. The physical protection of radiological sources, at medical facilities, food irradiation enterprises, and disposal sites, continues to raise concerns as well. In addition, Russia is facing difficulties disposing of these sources: the disposal site in Northwest Russia reached capacity and has already been closed; most of the nations' other disposal sites will reach full capacity in the next half decade. Without increased disposal capacity, the likelihood that sources will not be properly guarded increases.

The final problem Russia faces is in accounting for and monitoring its radioactive sources. Less than half of Russia's regions have functioning regional informational and analytical centers, the government bodies that are supposed to account for radiological sources. Russia's nuclear monitoring body, formerly known as Gosatomnadzor, is undergoing structural changes—the distribution of functions between Federal Atomic Energy Agency and the monitoring body remain unclear. Even before restructuring, Gosatomnadzor had difficulty monitoring and protecting radioactive sources that were used by military units that have been disbanded, as well as monitoring military radioactive waste disposal sites in disbanded units, and did not have the computing and administrative capacity to fully utilize the data it collected from other users of radiological sources.

Russia has a wide range of radiological materials, used in particular by the nuclear industry, the oil industry, and in medicine. Most radioactive material, such as natural uranium, low-enriched uranium, many short-life isotopes, and low-level radioactive waste, are not useful for a radiological dispersal device (RDD). However, Russia has a range of more powerful radiological sources that could be used in an RDD. This is of particular concern as several Chechen terrorist groups affiliated with al-Qa'eda have indicated their interest in the acquisition of such a device. Although an RDD would not inflict the mass casualties of a weapon of mass destruction, it could create mass panic, which in turn is likely to result in casualties as well as significant economic harm.

Russia has several organizations tasked with protecting and monitoring radioactive materials. The regulations guiding these organizations, both civilian and military, continue to be in flux. The following section begins by giving a brief overview of laws and regulations, identifying in particular those areas where regulatory change may have an effect on nuclear and radiological safety. The brief then looks at organizations tasked with overseeing these materials. Finally, we examine the vulnerability of various categories of radioactive materials to theft.

The main laws and rules regulating nuclear and radioactive materials in Russia at present are:

Under the law On Atomic Energy, a certificate (svidetelstvo) is required to transfer ownership of radioactive installations, radioactive sources, storage facilities, nuclear materials, radioactive materials, and radioactive waste that are not used for military purposes to non-state users. However, the procedure for obtaining such a certificate has yet to be defined.[3] The law also requires that organizations that possess radioactive isotopes hold a license, issued by the Federal Inspectorate for Nuclear and Radiation Safety (Gosatomnadzor, now called the Federal Nuclear Supervisory Service, soon to become part of the Federal Service for Environmental, Technological, and Nuclear Inspection—see below). The licensing process was initiated in 1998. By the end of 2001, 2121 of 2473 organizations possessing such isotopes had licenses. The remaining 4% were chiefly new and reorganized organizations (260 had already applied but not yet received licenses by the end of that year).

While the licensing system is thus largely in place, regulation of radioactive isotopes in Russia is still in flux. The law On Technical Regulation, signed into law by President Putin on December 27, 2002, requires the drafting and adoption of new requirements for the production, exploitation, storage, transport, and final disposition of radiological materials.[4] These new regulations must be adopted within seven years. Officials from the FAAE and former Gosatomnadzor have been particularly worried by the fact that the law requires the new regulations to set minimum requirements for nuclear safety. They argue that this contradicts existing Russian and international requirements that set maximum safety standards, and that the new law contradicts the principal of putting safety above all other considerations when dealing with nuclear energy.[5] In addition, Article 7 of the law On Technical Regulation states that only those requirements that are included in the technical regulations can be compulsory. This would seem to preclude the FAAE and the nuclear inspectorate from issuing compulsory requirements to individual facilities on a case-by-case basis, or making international agreements that require a particular facility to meet a requirement that has not been included in the existing regulations.[6] Even more problematic, the law On Technical Regulation requires the wholesale change of the existing system for certifying equipment and technologies in the nuclear sphere. According to Gosatomnadzor experts, the law would exclude FAAE participation in accrediting or certifying such equipment, and would largely exclude the former Gosatomnadzor as well as the State Standards Bureau (Gosstandart), as these governmental bodies are all involved in state policy or monitoring in the nuclear sphere. Russian nuclear experts are calling for excluding the nuclear sphere from the law On Technical Regulation.[7]

As far as the Center for Nonproliferation Studies (CNS) has been able to ascertain, there are no current plans to implement a certificate system to document the transfer of radioactive isotopes. Instead, the Russian Ministry of Atomic Energy has been trying to amend the provisions of the law On Atomic Energy requiring certificates. While a bill altering these provisions was approved by the government in 1999, and passed by the State Duma in 2000, the Federation Council rejected the bill, and a Duma-Federation Council joint commission to address the issue was set up on March 15, 2001.[8] On January 20, 2003 Deputy Minister of Atomic Energy Mikhail Solonin was put in charge of pushing the bill.[9] There have been no statements to the press regarding the terms of the amended bill yet.

The Federal Atomic Energy Agency, formerly known as the Ministry of Atomic Energy, is responsible for the production of all nuclear materials in Russia. The Federal Nuclear Supervisory Service inherited the role of monitoring nuclear activity, including the development of regulatory guidelines for nuclear and radiation safety, material control and accounting, physical protection, radioactive waste management, and industrial safety; inspection activities, involving the verification of compliance at facilities with set regulations; licensing; and assessment, including the making of recommendations to other agencies and the government, from the Federal Inspectorate for Nuclear and Radiation Safety.

The exact role of these two government bodies is currently in flux. On May 20, 2004, Russian presidential edict No. 649, Questions of the Structure of Federal Organs of Executive Power, created a new Federal Service for Environmental, Technological, and Nuclear Oversight, pulling the Federal Nuclear Supervisory Service out of the Ministry of Industry and Energy but combining it with the services that supervise environmental and technical matters. As of mid-July, no statute had been issued governing the new service. Meanwhile, government Statute No. 316 of June 28, on the Federal Atomic Energy Agency, gave the agency the power independently to issue regulations that delimit the functions of federal bodies involved in environmental impact assessments and the adoption of preliminary design and project documentation. As of July 13, 2004, however, it had yet to issue any regulations in this regard. The future independence of the regulatory service will be determined by these documents.

The majority of radiological materials is not suitable for the construction of a an RDD, and will not be discussed here. Of those materials of concern, radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) used in lighthouses on Russia's northern and eastern coasts are a particularly acute problem, and have even been stolen by children. The number of orphaned sources in Russia has diminished in the past several years, but remains an issue. The physical protection of sources, at medical facilities, food irradiation enterprises, and disposal sites, continues to raise concerns as well. In addition, Russia is facing difficulties disposing of radioactive sources: the disposal site in Northwest Russia reached capacity and has already been closed; most of the nations' other disposal sites will reach full capacity in the next half decade. Without increased disposal capacity, the likelihood that sources will not be properly guarded increases. The final problem Russia faces in protecting its radioactive sources from would-be terrorists is the difficulty Gosatomnadzor has had monitoring and protecting radioactive sources that were used by military units that have been disbanded, as well as monitoring military radioactive waste disposal sites in disbanded units.

During the Soviet era, radioisotope thermoelectrical generators (RTGs) were built to power naval navigational aids, some military facilities, and meteorological stations. Powered by Strontium-90, RTGs contain 30,000-300,000 curies, and could thus provide material for an RDD.[10] As of 2003, the total number of RTGs in Russia was 998, of which 829 were operational and 169 were in storage.[11] The RTG-powered lighthouses are located on the Kola Peninsula, northern Siberia, and the Russian Far East. In addition, there are two RTGs that were declared lost in the Okhotsk Sea in transport accidents.[12]

RTGs have been targeted by thieves on several occasions. One was recovered from the floor of the Gulf of Finland on March 28, 2003. The total radiation of the 5 kilogram, 10-cm strontium cylinder was 40,000 curies, while radioactivity 20 cm from the object was about 1000 roentgen/hr, enough to deliver a fatal dose within minutes. Thieves had stolen the generator, removed about 500 kg of metal shielding the radioactive core, and dumped the remainder onto the ice only 200 meters away. The core, with a surface temperature of 300-400 degrees Celsius, melted through the ice and fell into the sand on the bottom of the gulf. Radon specialists, together with the navy and police, raised the generator core to the surface using pitchforks and spades. The core, which was intact, was transported for temporary storage to Radon.[13] In June 2001, ten lighthouses near Vladivostok were reported as out of commission due to tampering by thieves.[14] While most thefts involve stealing metal from the lighthouses, there have also been attempts to take the RTG itself. In December 2000, thieves tried to take the generator from one of the forty-some lighthouses in Kamchatka, allegedly in order to provide heat and electricity in their apartment. However, they damaged the shielding and abandoned the generator.[15] Another RTG was abandoned by naval personnel when they were unable to transport it to a lighthouse they were attempting to service. The RTG was left near a residence in Plastun, Primorskiy kray, and remained there for about a year and a half. Radioactivity near the object was about 4-500 mR/hr. The existence of the RTG was widely reported in the press, increasing the risk that it could have been stolen.[16] The majority of the lighthouses, both civilian and military, are vulnerable to theft. A commission examining the Chukotka lighthouses in September 1997 reported that only three lighthouses had physical protection. One of the lighthouses was found abandoned near a farm some 100 meters from residential housing.[17] The location of many of the RTGs is well known, while a 2002 Russian Nuclear Regulatory inspection commission could not even locate some of the lighthouses.[18]

Norway was the first foreign nation that took on the RTG problem, committing in February 2001 to replacing 20 RTGs with solar batteries.[19] In June 2002, Norway signed another agreement to replace RTGs, pledging an additional NKr 1.5 million (approximately $191,000).[20] Subsequently, the United States initiated an RTG removal program. In November 2003, the Nuclear Radiological Threat Reduction Task Force was created at the Department of Energy to address the threat posed by high-risk radiological materials.[21] The RTG program has come under the purview of this task force, which has developed a program that is slated for implementation in 2004. The program will involve several pilot projects, including conversion of beacons and lighthouses to solar power, wind power, and the use of commercial power grids in certain locations. Department of Energy officials have been meeting with Norwegian officials to learn from their experience; the United States intends to undertake the removal of these RTGs on a larger scale than the Norwegian program has to date. There are currently several Russian entities that have made proposals regarding the methods and location for the ultimate disposal of the RTGs. The Russian government will decide on the disposal method, and then request assistance to implement it. However, removal of RTGs does not require that a decision on their ultimate disposal first be made.[22] Other nations are also considering providing help in this area. As of May 2004, Canada was discussing a Norwegian proposal to join the ongoing Norwegian program, as well as alternative arrangements, including participation in U.S. RTG removal project.[23] Other nations expressing interest in providing additional assistance for the removal of Russia's RTGs include France, Germany, and Japan. France has proposed extending its assistance in remediation at the ex-naval base in Gremikha, Murmansk Oblast, to cover generators in the vicinity of Gremikha. No decision has been made on how many RTGs this might cover, but the project could cover their transportation, dismantlement, and replacement with more environmentally friendly generators. French discussions appear to be leaning towards a bilateral effort that would be complementary to Norwegian efforts.[24] Germany and Japan have mentioned an interest in assisting in this area, but it would appear that this intention has yet to be followed by discussions with the Russians. To date, the United States is the only country that is likely to work on RTGs on Russia's Pacific coast, though presumably any Japanese program would also focus on the Pacific.

The number of orphaned sources in Russia has been diminishing since the end of 2001, when the licensing of enterprises using radioactive sources was largely completed. However, according to Gosatomnadzor, some orphaned sources remain, while sources continue to become orphaned. In 2002, for instance, 51 sealed sources were reported lost, and some 100 orphaned sources were discovered.[25] Finding these sources continues to be urgent. Radon, the enterprise that runs Russia's 16 regional disposal sites for radioactive waste from medical, scientific and technical facilities, has been a key player in this regard.[26] One of Radon's tasks includes monitoring the local environment. In addition, sources are discovered by people who find containers marked with radiation hazard symbols, who have then called Radon to pick them up. Local divisions of Gosatomnadzor are also involved in this effort.[27] In the first half of 2002, for instance, the Far Eastern division of Gosatomnadzor reported three discoveries of radioactive materials: an aviation ice detector containing strontium-90 found during building renovations in Khabarovsk, Khabarovsk Kray on May 15, a radiation source containing cesium-137 (emitting 107 Bq) discovered at a tourist resort in Primorskiy Kray on March 19, and a container holding 22 smoke detectors (that use very small amounts of plutonium) in the basement of an administrative building in Magadan on February 28. Material on these cases was turned over to the police so that they might be investigated.[28] Gosatomnadzor inspectors also have been gradually examining facilities to determine if they are contaminated or hold any abandoned radioactive materials.

Regional administrations are also involved in creating inventories of radioactive materials in their regions. They are supposed to have created Regional Informational and Analysis Centers to carry out yearly inventories. However, only 58 regions (of 85) have formally created such centers,[29] and they are only fully functioning in 39 (of 85) regions.[30] In addition, Gosatomnadzor has questioned the integrity of some of the inventories produced. In particular, the Urals branch of Gosatomnadzor has noted that inventories from the northern Urals have reported unaccounted-for radioactive sources and containers of depleted uranium.

While Gosatomnadzor reports that the majority of sources are held by facilities that hold licenses to own these sources, the physical protection of sources at facilities, such as medical facilities, food irradiation enterprises, and disposal sites, continues to raise concerns. Gosatomnadzor and, under Gosatomnadzor supervision, Radon, monitor the use of radiation sources at civilian enterprises. Gosatomnadzor has asked for increased education for monitors and the personnel using radiation sources alike. They point to the lack of a culture to promote the poor physical security of radiation sources.[31]

To date, there have been only a few cases of thefts. In 2001, Gosatomnadzor reported six thefts of radioactive sources, and one loss of a source not used in geophysical prospecting (there were 24 sources that were lost in boreholes during prospecting).[32] In the first half of 2004, there were several sources lost during prospecting.

Russia's 16 disposal sites are rapidly filling up. The Northwest region, in particular, is facing a crisis because the Arkhangelsk Radon facility was closed several years ago. Federal funds for reconstruction of the site have not been appropriated, while a new facility site has yet to be finalized. Regional facilities, therefore, have been unable to dispose of their radiation sources upon their expiration dates. In 2001, Gosatomnadzor arranged for the transfer of 92 sources in the region to the Izotop enterprise, which is licensed to transport and store radioactive materials. However, sources are again piling up. While some Radon facilities (such as Khabarovsk) have constructed new storage areas, many others will reach full capacity in the next 5-7 years. When sources are not promptly transferred to storage facilities at the end of their life cycles, the likelihood of theft or loss increases.

One Radon site location that has been particularly difficult to secure is the facility in Groznyy, the capital of Chechnya. In July 2000, a group of specialists from Lider, the center for high-risk rescue operations of the Ministry of Civil Defense Affairs, Emergencies, and Liquidation of Consequences of Natural Disasters, conducted a week-long highly secretive operation to detect and safeguard radiation sources at the facility.[33] However, many isotope sources had apparently gone missing before the operation,[34] while there are additional locations in Chechnya that have highly radioactive materials. In April 2003, powerful radioactive sources were found on the grounds of a destroyed chemical plant in Groznyy.[35] There are reportedly twelve missing radioactive sources in Chechnya today. Since the beginning of 2000, Radon has recovered 80 containers with radioactive materials in Chechnya, and removed them from the region. In addition, a Radon burial site in Chechnya's Tersk mountain range has been walled in and has posted guards.[36]

Foreign assistance programs at Radon burial sites, however, have begun to address the security problems at some of these facilities. In April 2002, the US Department of Energy's Radiological Threat Reduction program initiated its first security upgrade project at the Moscow Radon facility, the largest Radon site (some 80% of Russian radioactive wastes are sent to Radon Moscow).[37]

Besides storage facility problems, Russia faces difficulties bringing all sources to those facilities. Sources often remain at enterprises after their expiration date, in many cases due to a lack of funding. In Primorskiy Kray, a regional deputy governor was asked to assist the local Radon facility in its efforts to transport expired sources to the storage facility, and the kray donated 61,000 rubles (about $2,000) for this purpose.[38] In Irkutsk Oblast, some 60 expired sources remain at local enterprises, for financial reasons as well as a "lack of interest" in turning the materials over to Radon.[39]

Finally, there are those sources that have not been transferred due to technical difficulties. For instance, Minatom has yet to transfer Cobalt-60 sources at the Prikaspiyskiy Biological Resource Institute in Vladikavkaz, Dagestan (emitting 13.2 · 1014 Bq or 36,000 curies) to Radon Saratov. The transfer of other powerful radiation sources in the Don district to Radon has also been delayed.

Gosatomnadzor has identified particular difficulties in monitoring radiation sources when enterprises change owners or go bankrupt, as well as monitoring and protecting those radiation sources that were formerly used by military units that have been disbanded. In the latter case, the military does not always inform Gosatomnadzor of the existence of these radiation sources, or of radioactive waste disposal sites abandoned when units disband. Since Gosatomnadzor does not monitor the military's use of radiation sources, it relies on the military to inform it of radioactive substances that should be brought under its purview.

While there are many radioactive source materials in Russia, the number that would make effective nuclear or radiological weapons is limited. Many of these sources have yet to be sufficiently protected, and some would be simple for extremists to obtain. These sources, RTGs and sources used in the oil industry and hospitals are the strongest, most vulnerable sources. The storage of radiological materials that are no longer in use also remains problematic. Finally, the creation of inventories of radiological materials and a transparent oversight system that can truly monitor the use of these materials, remains critically important.

[1] "Pravila rassledovaniya i ucheta narusheniy pri obrashchenii s radiatsionnymi istochnikami i radioaktivnymi veshchestvami, primenyayemymi v narodnom khozyaystve," www.doc.softkompas.ru.

[2] Pravila fizicheskoy zashchity radiatsionnykh istochnikov, punktov khraneniya, radioaktivnykh veshchestv. Utverzhdeny Postanovleniyem Gosatomnadzora Rossii ot 16 yanvarya 2002g. No. 3.

[3] Law On Atomic Energy, in NIS Nuclear and Missile Database, www.nti.org.

[4] Zakon O tekhnicheskom regulirovanii, Ispytatelnaya pozharnaya laboratoriya Website, www.firelab.ru.

[5] Minatom Press Center, in "Nado li snizhat porog bezopasnosti" Parlamentskaya gazeta, October 30, 2002, in Tsentr strategicheskikh razrabotok "Severo-zapad" Website, www.csr-nw.ru.

[6] ZakonO tekhnicheskom regulirovanii.

[7] See V.S. Svintsov, "O vliyanii federalnogo zakona 'O tekhnicheskom regulirovanii' na obespecheniye yadernoy i radiatsionnoy bezopasnosti" and A.M. Bukrinskiy, "O neobkhodimosti vyvoda iz-pod deystviya federalnogo zakona 'O tekhnicheskom regulirovanii' obyektov ispolzovaniya atomnoy energii," in Vestnik Gosatomnadzora Rossii, No. 1, 2004, www.gan.ru.

[8]"Rossiyskaya federatsiya, Federalnyy zakon, O vnesenii izmeneniy i dopolneniya v statyu 5 federalnogo zakona 'Ob ispolzavanii atomnoy energii,' in AKDI Ekonomika i zhizn Website, www.akdi.ru.

[9] "Za prokhozhdeniyem zakonoproyekta po vneseniyu izmeneniy v zakon ob ispolzavanii atomnoy energii so storony Pravitelstva budet nablyudat zamministra RF po atomnoy energii M. Solonin," AK&M, in Intertek Information Agency, January 20, 2003.

[10] For information on various isotopes, radioactivity levels, and RDDs, see Charles Ferguson, Tahseen Kazi and Judith Perera, Commercial Radioactive Sources: Surveying the Security Risks (Monterey: Center for Nonproliferation Studies Occasional Paper, January 2003).

[11] United States General Accounting Office, "Nuclear Nonproliferation: U.S. and International Assistance Efforts to Control Sealed Radioactive Sources Need Strengthening," https://www.gao.gov/cgi-bin/getrpt?GAO-03-638, May 2003.

[12] The RTGs were lost in 1987 and 1997. "Radiatsionno opasnyye obyekty organizatsiy narodnogo khozyaystva."

[13] Oleg Bodrov, "Radioaktivnaya bomba dlya Baltiki," Pravda.ru, April 17, 2003; "Ugroza radioaktivnogo zarazheniya Finskogo zaliva," Radio Svoboda, April 17, 2003.

[14] Aleksandr Maltsev, "Kogda oslepnet posledniy mayak…" Vladivostok, https://www.vladnews.ru, June 28, 2001.

[15] Leonid Skudar, "Opasny ne izotopy," Vesti, December 22, 2000.

[16] Yevgeniy Suvorov, "Oblucheniye po-flotski," Vladivostok, www.vladnews.ru, April 17, 2001; Yevgeniy Izyurov, "Khronika luchevoy bolezni," Vladivostok, https://www.vladnews.ru, March 26, 2003.

[17] "Gosdoklad o sostoyanii okruzhauishchey sredy RF v 1998 godu," State Environmental Protection Service of the Ministry of Natural Resources Website, www.eco-net.ru.

[18] Thomas Nilsen, "Nuclear Lighthouses to Be Replaced," Bellona Foundation Web Site, February 2, 2003.

[19] Norway undertook to finance the project in its entirety. The contract was originally for NKr 2,2053,600 (about $227,000). Prilozheniye k protokolu No. 19 zasedaniya Komissii po voprosam mezhdunarodnoy tekhnicheskoy pomoshchi pri Pravitelstve Rossiyskoy Federatsii, "Perechen proyektov dlya priznaniya tekhnicheskoy pomoshchyu (rassmotreny rabochey guppoy Komissii po voprosam mezhdunarodnoy tekhnicheskoy pomoshchi pri Pravitelstve Rossiyskoy Federatsii 23 aprelya 2001 g.)" Informatsionnaya sistema Komissii po voprosam mezhdunarodnoy tekhnicheskoy pomoshchi pri Pravitelstve Rossiyskoy Federatsii Web Site, www.isr.ru

[20]"Norwegian government to allocate money to Murmansk region for nuclear safety projects," The Nuclear Chronicle from Russia, Bellona Foundation, www.bellona.no, June 11, 2002.

[21] "NNSA Refocuses Threat Reduction Efforts to Return Nuclear Research Reactor Fuel; Will Consolidate DOEs Threat Reduction Efforts," U.S. Newswire, April 14, 2004; in Lexis-Nexis Academic Universe, www.lexis-nexis.com.

[22] CNS interview with U.S. Department of Energy official, May 12, 2004.

[23] CNS interview with Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade official, May 18, 2004; CNS interview with U.S. Department of Energy official, May 12, 2004.

[24] CNS e-mail communication with French official, May 18, 2004.

[25] In 2000, 245 sealed sources were reported lost. United States General Accounting Office, "Nuclear Nonproliferation: U.S. and International Assistance Efforts to Control Sealed Radioactive Sources Need Strengthening," p. 12. Gosatomnadzor reports discovering over 100 orphaned sources in more than 30 incidents. "Radiatsionno opasnyye obyekty organizatsiy narodnogo khozyaystva," Gosatomnadzor report on 2002, www.gan.ru.

[26] Fourteen Radon facilities are subordinate to the Russian Federation Construction Committee, via regional divisions of that committee, while Radon Moscow and Radon Bashkortostan are subordinate to the City of Moscow and Baskortostan Republic, respectively. "Informatsiya po voprosam razmeshcheniya radioaktivnykh otkhodov i stroitelstva novykh khranilishch," Gosatomnadzor Web Site, www.gan.ru; see also Russian Federation Construction Committee orders # 87-90, March 21, 2003 and #18, January 18, 2003, regarding territorial directorates of the Construction Committee, in Integrum Techno, www.integrum.ru.

[27] "Radiatsionno opasnyye obyekty organizatsiy narodnogo khozyaystva."

[28] See "Narusheniya v rabote podnazornykh obyektov," February, March, and May 2002, www.gan.ru.

[29] "Radiatsionno opasnyye obyekty organizatsiy narodnogo khozyaystva," Gosatomnadzor report on 2002, www.gan.ru.

[30] Rashid Alimov, "Nuclear Officials Talk About What Isn't There," Bellona, July 9, 2004, www.bellona.no.

[31] "Radiatsionno opasnyye obyekty organizatsiy narodnogo khozyaystva."

[32] Ibid.

[33] Russian Public TV, July 10, 2000, in "Special Team Returns to Moscow after Radioactive Cleanup in Groznyy," BBC, July 12, 2000.

[34] Yuriy Gladkevich, "Poshel v gory," Profil, March 20, 2000, p. 16; Yevgeniy Antonov, "Ugroza terroristicheskogo akta s ispolzovaniyem oruzhniya massovogo unichtozheniya iz Chechni," Yadernyy kontrol, April 1, 2001.

[35] According to Radon Groznyy Director Ziva Kadyrov, there were originally 17 sources at the plant, one of which had been stolen by teenagers from the neighboring village of Kirov. Two of the teenagers died from radiation sickness. Kadyrov said that a plan to decontaminate the chemical plant has been submitted to the government of Chechnya for approval. Meanwhile security has been stepped up around the facility. "Groznyy: V zavodskom rayone obnaruzhen istochnik moshchnogo radioaktivnogo izlucheniya," Regions.ru, April 16, 2003.

[36] Ibid.

[37] United States General Accounting Office, "Nuclear Nonproliferation: U.S. and International Assistance Efforts to Control Sealed Radioactive Sources Need Strengthening," p. 24.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Ibid.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest on nuclear and biological threats.

“The bottom line is that the countries and areas with the greatest responsibility for protecting the world from a catastrophic act of nuclear terrorism are derelict in their duty,” the 2023 NTI Index reports.

The only public database of its kind, includes global nuclear & radiological security trends, findings, policy recommendations, and interactive visualizations.

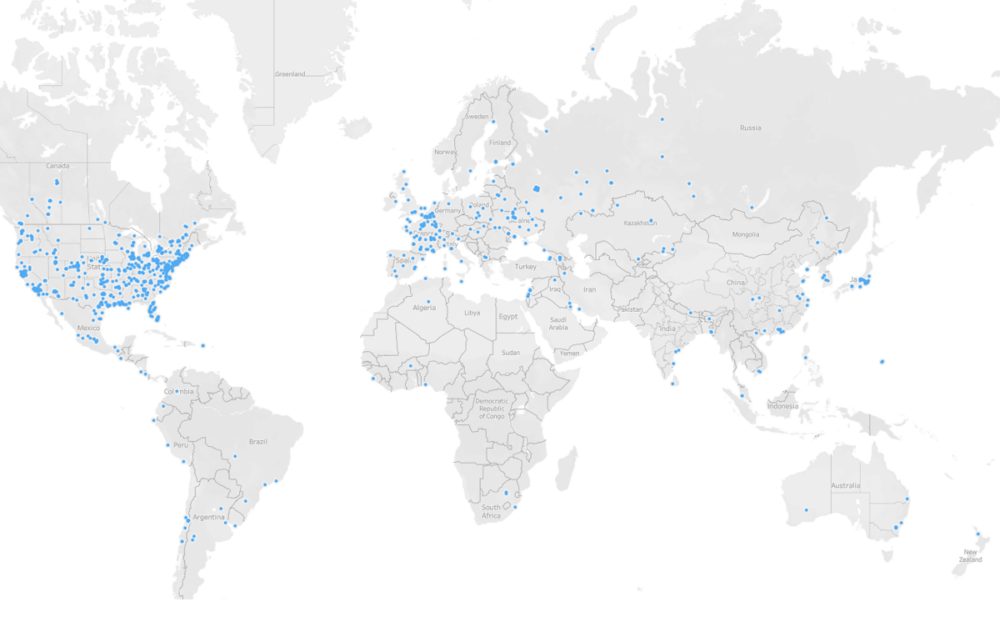

Archives of Global Incidents and Trafficking Database, 2013-2018. (CNS)