Atomic Pulse

Biosecurity Imperative: An Urgent Case for Extending the Global Health Security Agenda

In

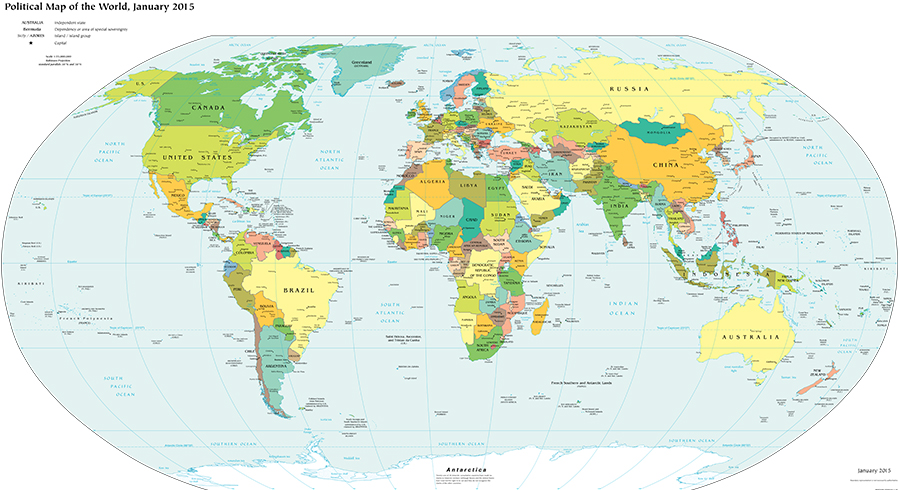

2014, dozens of governments, international organizations and non-governmental groups

from around the world came together to accelerate global capacity to prevent,

detect, and respond to urgent infectious disease threats and to elevate health

security as a global priority. The Global Health

Security Agenda (GHSA) was conceived as a five-year initial effort that

would run through 2019 – but it’s already clear that this vital partnership

with a proven track record must be extended well into the future.

Next

week in Seoul, the Republic of Korea will convene the Steering Group of the GHSA

to discuss next steps to advance the agenda, including extending the group’s

mandate. Recognizing that the GHSA’s

work has never been more vital and would be impossible to replace, more than 100

health and health security organizations and companies operating in over 150

countries, including the Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI), this week banded together to urge GHSA’s extension for at least another five years. Here’s

why we signed on.

As

part of our mission to address the threats from weapons of mass destruction and

disruption, NTI works to reduce biological risks posed by bioterrorism,

pandemics, and advances in technology. Over the last three years, the GHSA has

been a major driver to elevate preparedness for biological threats as a top national

security priority and health imperative for all countries. For that reason, NTI

strongly supports the continuation of the GHSA with a focus on accountability,

commitments, financing, and a continued and strengthened inclusion for biosecurity as a core

priority for both the health and security communities.

For

the past decade, global biological threats have increased in likelihood and

import – magnified by air travel, conflict, urbanization, and terrorist

interest in weapons of mass destruction. When the GHSA was launched in 2014, its

mission was to address future epidemic threats and, ultimately, to achieve a

world safe and secure from biological threats, whether caused by a naturally

occurring infectious disease outbreak, a deliberate bioterrorism attack, or an

accidental laboratory release. The GHSA has now succeeded in designing the global

architecture necessary to assess, measure, and sustain advances in global

preparedness for epidemic threats, a global architecture that would be nearly impossible

to recreate. Although not all countries choose to participate, the 59-country

GHSA serves as an incubator for innovative and new approaches to tough tasks –

a way to convene multiple sectors and communities for debate and, most

importantly, for action.

In

recent years, Ebola, the SARS, MERS, H1N1 pandemic influenza, and the anthrax

attacks have all been major international events, and although these events

exercised global response capacity, there’s no question that the world is still not prepared for a

pandemic involving a highly lethal biological threat that transmits readily

between people. Consider:

· On prevention, an

increasingly vital GHSA element: During the Ebola epidemic, the three affected

West African countries banded together, averting country collapse and the

potential creation of new safe havens for conflict and terrorism. But, secure

and consolidated sample storage and transport during and following the crisis

has continued to be a major issue considering terrorist interest in weapons of

mass destruction. Furthermore, this area will only continue to grow in need as new advances in

technology now portend the possibility of terrorist creation of new and

modified pathogens

– underscored by the recent

creation of the horsepox virus in Canada.

· On disease detection,

another integral GHSA focus area:The global leaders that launched the GHSA on

February 13, 2014 did not yet know that the first cases of Ebola had already

surfaced in Guinea. Those initial cases occurred in December 2013 but were not

reported until March, 2014 – nearly three months later. National disease

detection and reporting systems and a global biosurveillance network remain

major gaps in the global architecture for reducing biological threats.

· Finally, on

response: The initial ineffective global response to Ebola in West

Africa contributed mightily to the deaths of over 11,000 people and an epidemic

that went on to devastate West Africa, cause global fear and panic, wreak havoc

on international transportation – subsiding only after multiple deployments of

the international public health experts, investments of billions of dollars,

and the deployment of the United States military through Operation United

Assistance.

It’s clear that although

much has been done to improve capability to create global medical countermeasures

– and the launch of the Coalition for

Epidemic Preparedness Innovations is an important step forward – the world

is still many years away from a global “on demand” capacity to produce, test,

and distribute vaccines and therapeutics for emerging threats. Every

country must make prevention, detection, and response for biological

threats a top-tier priority – and GHSA will continue to be instrumental for

keeping leaders sighted.

GHSA: Successes and Areas for Continuing

and Future Focus

The GHSA

was created to resolve major, longstanding global challenges to save lives,

avoid economic loss, and avert political instability as the result of

biological threats. Through the GHSA, measurable progress is – for the first

time – being made on each of these previously intractable issues. Now is the time to accelerate our

efforts, not stop them.

1. Measurement, Accountability, and

Transparency

Before

the GHSA was launched in 2014, there was no consensus on metrics for pandemic

preparedness, and there were no globally-agreed indicators for such

measurement. At least 80% of countries had missed the 2012 deadline for

compliance with the International Health Regulations (IHR), which are the

pandemic preparedness standards that all 194 World Health Organization (WHO)

Member States have signed on to achieve. A major reason for this historic

misstep was the lack of agreed metrics for showing improvements. GHSA was created in large part to create

these measurable steps, thereby paving the way for governments, donors,

development banks, and the private sector to invest in biological threat reduction

with confidence. Within one year of its creation, the GHSA developed

11 targets with indicators. These were then

adopted by GHSA participating countries in 2015 and built into

the WHO IHR monitoring and evaluation effort the following year.

Furthermore,

in 2014, no mechanism existed for independent, external assessment of country

capacity to prevent, detect, and respond to public health emergencies of

international concern. Countries were

conducting varying self-assessments, which were not published, largely

conducted by health ministries, and without the type of multi-sectoral,

independent evaluation required to assure a realistic evaluation and a stepwise

plan for measurable improvement. Within one

year of its creation, the GHSA and its leadership developed a framework for

such evaluations and then pilot tested and published external peer evaluations

in six countries and collaborated with the WHO in the development of a

voluntary global Joint External

Evaluation (JEE)

that has now been conducted in more than 40 countries.

This

is a phenomenal track record that most global initiatives could only aspire to

attain. And we shouldn’t stop there. All countries should undergo and publish

an evaluation, and much work remains to

fill identified gaps and establish accountability for commitments and

improvements.

NTI,

in partnership with the Economist Intelligence Unit and The

Center for Health Security at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public

Health, is developing a Global

Health Security Index

to provide a public benchmarking of global health security conditions—building

on the JEE, modelling many of the lessons learned from NTI’s successful

first-of-its-kind Nuclear Security Index, and informed by an international

expert advisory group. The GHSA should continue

promote independent monitoring and accountability, public-private partnerships

to assist countries, and commitment tracking.

2. Biosecurity as a Public Health

Imperative

Before

the GHSA was conceived, it was rare for countries to have in place a dedicated

coordination mechanism for countering biological threats that includes the

health, security, development, defense, and agriculture sectors. Even in these

countries that did have such mechanisms, the United States among them, these

communities were not using common metrics for measuring programmatic activities

with similar goals. Although global health experts in countries within East

Africa, the Middle East, and South and Southeast Asia have espoused concerns

about bioterrorism, many health experts – often from developed countries – have

remained wary about including biosecurity as a core component of public health.

The IHR itself didn’t even contain specific metrics related to biosecurity. Shortly

after its inception, the GHSA set to work and, in short order, developed

initial biosecurity

metrics

and activities that the health

and security communities from participating countries could each agree upon,

including metrics urging consolidation of especially dangerous pathogens and

maximizing the use of effective modern diagnostic technologies that don’t

require culturing and improve disease detection and surveillance. However, in

this area of the GHSA, much remains to be done to regularly bring security

experts to the GHSA table, to build additional bridges between the GHSA and

other initiatives with a core competency in biosecurity, such as the Global Partnership

Against the Spread of Weapons and Materials of Mass Destruction, and the United Nations Security Council Resolution 1540

Committee.

The GHSA could and should help inform and create

consensus on global biosecurity norms that reduce the risk posed by emerging

technologies that are increasingly accessible and portend terrorist capability

to create and modify dangerous pathogens. As the GHSA extends, this area

requires more attention, as do other vital areas like One Health, and the

creation of more accessible tools and technologies for real-time

biosurveillance.

Additional work is needed to catalyze more

attention to this vital area of the Agenda.

The GHSA should place additional emphasis on inclusion of security

experts with an enhanced focus on biosecurity. The GHSA must also consider the

urgent need to develop global norms and incentives for reducing risks posed by

advances in technology that now enable the creation and modification of pathogens

with pandemic potential.

3. Financing and Sustained Attention by

Leaders – No More Cycles of “Panic” and “Neglect”

Finally,

when GHSA was launched there were not – and still are not – global mechanisms

for leveraging financing from host countries, donors, development banks, and

private sector companies to fill specific health security gaps. Historically,

global leaders pay attention to (and finance) biological threats during an

ongoing outbreak. However, attention tends to wane when a major crisis is not

at hand. During the

2014-2016 Ebola epidemic, the U.S. Government allocated $1 billion to assist 17

countries to achieve the GHSA targets. The International

Working Group (IWG) on Pandemic Preparedness Financing recently called on

all countries to be assessed and to develop plans to finance identified

gaps.

The GHSA is a country-driven effort, and

the call to action within the IWG report should be heeded. The GHSA should

catalyze the development of a mechanism to kick start financing for low-income

countries, including sustainable host country financing strategies, plug-ins

for private sector support, and synergy with development bank assistance.

These

goals must remain at the forefront of the global agenda, and the GHSA has

proven itself as a crucial mechanism for incubating creative approaches to take

next steps. Quite simply, the world cannot afford to lose this vital and

effective global partnership.

Stay Informed

Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest on nuclear and biological threats.

More on Atomic Pulse

Get to Know NTI: Aparupa Sengupta

Aparupa Sengupta, senior program officer for NTI’s Global Biological Policy and Programs team (NTI | bio), sat down with NTI’s Mary Fulham for the latest in Atomic Pulse’s “Get to Know NTI” series.

2022 Next Gen for Biosecurity Competition Challenge: Developing New Verification Strategies for the Biological Weapons Convention

Today, leaders preparing for the BWC’s Ninth Review Conference in August are exploring whether the global community can leverage increased attention and political will to strengthen the BWC by building mechanisms that increase transparency and trust with the goal of reducing the risk of global catastrophic biological events. A particular aim is determining whether there are effective and politically viable ways to enforce the treaty.

NTI at 20: Hayley Severance on the Next Pandemic, Cross-Border Collaboration on Biosecurity, and Engaging Young Leaders

An epidemiologist focused on preventing catastrophic biological events and building health security capacity around the world, Hayley Anne Severance brought her expertise to NTI’s expanding biosecurity team in 2018.