Jeffrey Lewis

Director of the East Asia Nonproliferation Program, The James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies

How Is Information Technology Changing Society?

How Is Information Technology Changing Public Policy?

Prologue: What Happened At Kumchang-ri, North Korea in 1994?

Did Iran Have A Secret Nuclear Facility in 2014?

How Is Information Technology Changing Society?

The information revolution is changing human society in ways big and small. Consider the seemingly small question of how we share vacation photographs. When you were young, how did your parents share vacation photos?

Here is how we did it in the 1980s. My Dad had a single-purpose analog device called a camera. He used the camera to make a picture by exposing film to natural light. Each roll of film could record only 24 exposures and needed to be stored carefully. When Dad was out of exposures, he removed the film and hand-carried it to a shop where he paid someone to use a chemical process to develop pictures from it.

A few days later, he returned to the shop to pick up the photos. If he was smart, he had remembered to order copies of the pictures. Then he could take one of the copies, place it in an envelope with a stamp, and a series of human beings employed by the US Postal Service would carry it to my grandparent’s home. Most of the time.

Having done all this, Dad had successfully shared a picture. But my grandparents couldn’t share that picture with anyone else, unless those people came over to look at the picture. And, unless Mom or Dad remembered to write “Chetek, Wisconsin 1983,” in ink on the back, a few years later Grandma and Grandpa had no recollection of who took the picture, let alone where or when it was taken.

There were, of course, a few variations on this process. Your Dad might be the kind who develops film at home in a dedicated darkroom. Or maybe Mom used a Polaroid instant camera. Or maybe your parents were the weirdos who took exotic vacations and paid to have the photographs turned into slides, which they lugged – along with a projector – down to the basement of their church to show the local Boy Scout troop.

But the bottom line is that, no matter how your parents did it, saving and sharing information was very labor intensive – and therefore expensive. It was much harder for something to go viral when the cost of every transaction was so much greater than it is today.

Now consider your smart phone. It contains a camera, which records an instant digital image. A 16GB iPhone can hold more than 2,000 images, but chances are you use space for other things your phone can do like take high-resolution videos or record audio. You use the same device to access the internet, from pretty much anywhere in the world, to share still images, video or audio with everyone in the world. You can email it, upload it to Dropbox, or post it on Facebook, Twitter or Instagram. And your friends can look at the pictures instantly using their smartphones and share them the same way with anyone else in the world. Unlike the pictures your Mom and Dad took, these can be encoded with metadata about the time, location and even type of camera that took the picture, as well as where and when the user uploaded it. The cost of recording, saving and sharing data is asymptotically approaching zero, save for the occasional data-roaming horror story. Which is why cat videos now go viral.

How Is Information Technology Changing Public Policy?

The information revolution has much bigger implications than just viral cat videos. Well, a little bigger anyway. It is also changing how journalists, academics and government officials approach public policy problems like the spread of nuclear weapons.

If you think about the field of nuclear weapons, it was until recently largely about telling. Someone might tell you about an event or a place. Even if you were lucky enough to have participated in an important event or visited someplace otherwise off limits, all you could do is tell someone else about it. Telling, as a method of communication, is essential – but it has it limits. Telling is an inefficient way to convey data, and is subject to all sorts of corruption and interference. How do you know when what you are being told is true? How do you know that the person telling you has it exactly right? We all know that stories tend to get better with every retelling.

On occasion, photographs of a foreign nuclear facility might be published in a newspaper or a magazine. These were usually pretty grainy, but they were still a really big deal. That’s because showing conveys a lot more data. The saying that “a picture is worth a thousand words” probably understates the ratio of data that can be conveyed in an image compared to text. The Central Intelligence Agency, for example, was able to estimate the size of the Soviet Union’s first enrichment plant by recreating a map of the electricity grid seen in a picture of the Soviet equivalent of Look magazine. The photograph had been censored – the plant had been cut off – but analysts were able to develop a model of the entire network and correctly surmise how much power was going to the censored site.

Today, this analysis would have been much easier – the Russian magazine, the image itself and all the information about power plants and substations would have been easy to find online.

As a result, we have started to take this sort of analysis for granted. When the United States, France and UK released dossiers showing that Syria was behind the chemical weapons attacks on Ghouta, many people were disappointed that they could read far more convincing evidence on websites like Bellingcat that used social media extensively. While the new tools are not purely visual, showing is an excellent metaphor for the data rich environment that the information revolution has created.

Prologue: What Happened at Kumchang-ri, North Korea in 1998?

Long before the 2014 allegations that Iran had a secret nuclear facility, policymakers grappled with similar questions in North Korea. Unlike the Iranian case, which happened during the information-rich age of showing, the North Korean case occurred during the age of telling. It illustrates the stark differences between nuclear detective capabilities then and now.

During the early 1990s, the United States and North Korea made a deal to end North Korea’s nuclear weapons program, called the Agreed Framework. Under the terms of the deal, North Korea froze its nuclear weapons program in exchange for international assistance and better relations with the United States. The Agreed Framework was controversial, just as the current agreement with Iran is, and many members of Congress expressed reservations. In some cases, these reservations were expressed in rather colorful terms. Senator John McCain, for example, referred to the agreement as “appeasement.” Many people, including those who negotiated and supported the Agreed Framework, were concerned that North Korea would not live up to its obligations.

In 1998, the United States intelligence community obtained classified satellite images showing construction of a large underground facility near Kumchang-ri. The U.S. intelligence community was unsure what the purpose of the facility was, but it was being constructed by the same unit that had built the tunnels at North Korea’s Yongbyon Nuclear Research Center. Some analysts from the Defense Intelligence Agency concluded the underground project might be a secret underground nuclear reactor and reprocessing plant being built in violation of the Agreed Framework. Before the intelligence community could reach a judgment, someone leaked the information to the New York Times, which published the information under the headline: “North Korea Site an A-Bomb Plant, U.S. Agencies Say.”

The impact on policy was immediate. The Clinton Administration ordered a review of its North Korea policy by William J. Perry and began negotiating with North Korea for access to the site.

When the North Koreans finally showed a U.S. inspection team the site, they discovered that what the New York Times had been told was wrong. The site was suitable for neither a reactor nor a reprocessing plant. But the damage had been done. When the Clinton Administration ran out of time to negotiate a missile agreement to buttress the Agreed Framework, the months wasted looking into Kumchang-ri loomed large.

Case Study: Did Iran Have A Secret Nuclear Facility in 2014?

In 2014, something happened that was very similar to what occurred in 1998 with North Korea – but with a much different outcome. The outcome was different because today open source information provides new opportunities to verify compliance with arms control, disarmament and nonproliferation agreements.

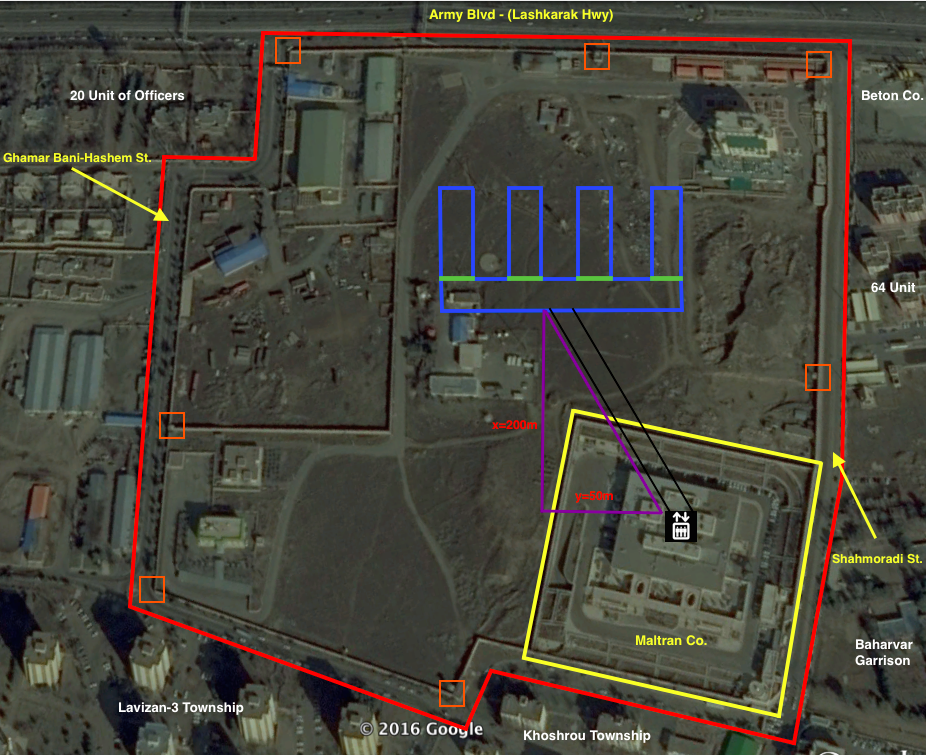

As Iran and the so-called E3/EU+3 were entering the final stages of negotiations on a deal to limit Iran’s nuclear programs, a dissident group alleged that Iran had constructed a secret underground nuclear enrichment center in the northwest suburbs of Tehran.

The briefing included a satellite image of the facility in question, as well as a mention of its name – Matiran. According to the dissidents, Matiran is a firm that manufactures security identification documents like passports and national identification cards. But they also claimed something odd – that there was a secret enrichment facility in the basement.

Matiran is a real company. You can find many of its employees on LinkedIn. Representatives from Matiran routinely attend conferences for the secure document industry, which is where they make contacts with the foreign firms that supply them with state-of-the-art technologies for making documents.

Thanks to all this, as well as the images released by the dissidents, it was easy to locate the Matiran site in satellite images. As discussed in greater detail in Module 2, there are many mapping applications that provide free imagery, including Google Earth and Maps, Bing Maps, and Nokia Here. One can also purchase imagery from commercial firms, although in this case it was not necessary. Google Earth had 30 pictures of the site, including 7 taken between 2004 and 2008 when it was allegedly under construction.

The dissident group alleged that Iran had constructed an underground facility between 2004 and 2008. Normally, such an underground facility would be constructed using what is called the “cut-and-cover” method. A construction firm excavates an area, constructs the building, and then covers it with earth. This is how Iran constructed the underground enrichment facility at Natanz.

Satellite images did not indicate any unusual construction at the site. Moreover, there were no obvious signatures of an underground centrifuge facility such as ventilation or a power substation – both of which are visible at the underground Fordow Fuel Enrichment Plant near Qom.

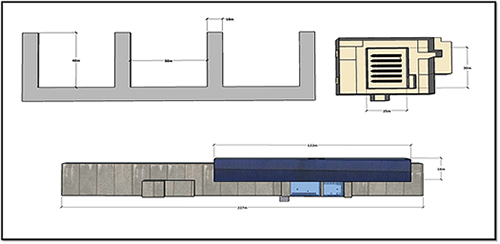

There were other problems with the story as well. The description of the alleged facility did not seem suitable for a centrifuge hall or even a research and development center. The dissidents described the facility as consisting of four narrow halls. Interestingly, the image provided by the dissidents was not to scale.

Using photographs of existing Iranian and North Korean centrifuge facilities, a graduate of the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey and researcher named Tamara Patton was able to construct three-dimensional computer models of these facilities to serve as a reference. The process is discussed in greater detail in Chapter 4.

What immediately became clear is that it would be very difficult to squeeze an enrichment facility into the configuration described by the dissidents. Most people only think about the centrifuges that perform the enrichment, but there is an enormous amount of space that must be dedicated to supporting infrastructure, such as the autoclaves that heat the UF6 gas contained in massive canisters. The models help show that what the dissidents were telling us isn’t likely to be true.

And then there was the issue of the door. According to the dissident group, Iran had installed a large lead-lined door in the facility to trap radiation. The dissidents even released an image labeled as “image of one of the shielding doors at Lavizan-3 installed at an underground hall.” This made little sense. Enrichment facilities don’t have a strong radiation signature, and they certainly don’t have lead lined doors. Images of the facilities at Natanz, for example, show the same sort of doors you might see anywhere else.

Outside analysts quickly determined the image was the same as one that could be found on a commercial website for an Iranian firm that manufactures heavy doors for bank vaults and so on. The dissidents quickly modified the story, releasing a copy of the picture to show that they had not simply downloaded it from the website.

Using the metadata embedded in the image it was possible to demonstrate that the photo of the door had been taken at a factory outside of Tehran – and not at the Matiran facility. Metadata techniques are discussed in greater detail in Chapter 5. Unfortunately, the metadata for the door did not include its location. But the picture did match a number of other photographs of the company’s factory, which suggests they were part of a set of photographs taken for its website.

Using these photographs, as well as the address of the company, it is possible to identify the exact location of the warehouse where the door is sited.

To recap: there are lots of problems with the story as told by the NCRI. The site doesn’t seem to show any construction or other evidence of an underground facility. The facility itself, as described, doesn’t look suitable for centrifuges, and the whole story about the door is just balderdash.

But what we really want is to find someone who had visited the Matiran site itself. There were several documents suggesting that Iran had brought VIP delegations to the site in 2011 and 2013, but it was unclear whether it was the same site.

As further discussed in Chapter 6, the information revolution has produced a massive amount of civil data for civil applications. You are far less likely to get lost while driving thanks to mapping applications. Those mapping applications even tell you about how heavy traffic is because your phone is recording your positional data.

Thanks to smart phones, there is a community of people who are dedicated to creating an open source alternative to commercial mapping programs called Open Street Map. What this means in practice is that there is a community of people who record their travel and upload its traces to the website. One of those persons, who I will call SK, uploaded four traces showing that he traveled to and from the Matiran facility on consecutive days in 2014.

SK’s traces demonstrated that he had been inside the facility. They also disproved something that the dissidents had claimed. Each point in the trace is time-stamped. You can see SK spent time sitting in traffic, but he flew past where the dissidents claimed there were roadblocks and other security measures.

I wrote to SK – which is easy enough in the age of email, and he was kind enough to email me back. He confirmed what should be obvious – that the facility made secure identification documents and that there was a steady stream of foreign contractors who visited the facility. The chance that there was a secret enrichment plant in the basement seemed far-fetched, if not ridiculous.

Of course, do we know that SK is a real person? It was also possible to confirm this person’s identity – although I will not reveal much of his personal information here. Such social media techniques are discussed further in chapter 7. He provided his name and general location in Europe, but withheld his employer and his address. However, he has an extensive social media presence that made it possible to confirm that he was who he claimed and that, in fact, he worked for the world’s leading producer of serialization machines. It was also possible to determine his address, hobbies and marital status. He is a real person – and seems like a pretty nice guy.

At the end of the day, the open source information overwhelmingly showed that what the dissidents had told us was not credible. There was no evidence of an underground facility, no evidence of a lead-lined door, no reason to think centrifuges would fit in such a strange facility, and there was a real live human being who had visited the site and seen nothing out of the ordinary.

The results of this investigation were published in a column in Foreign Policy entitled, “That Secret Iranian ‘Nuclear Facility’ You Just Found? Not So Much.” Almost immediately, the story died. The U.S. government stated it did not believe the claims made by the dissident group. Unlike in 1998, people believed the government. Thanks in part to open source sleuthing, the United States was not forced to interrupt delicate diplomatic negotiations to go on a wild goose chase.

Now explore each of the tools from the detective story: Commercial Satellite Images, Computer-aided Modeling, Metadata, Civil Data, and Social Media.

Your are currently on

Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest on nuclear and biological threats.

With the Center for Advanced Defense Studies, NTI demonstrates the viability of using publicly available information and machine learning to detect nuclear proliferation.

Progress on nuclear arms limitation and reduction is at risk, learn more and dismantle a nuclear weapon in augmented reality. (CNS)

The first detailed, exclusively open-source assessment of the five new nuclear weapon systems announced by Russian President Vladimir Putin in 2018