Jeffrey Lewis

Director of the East Asia Nonproliferation Program, The James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies

How did metadata help us solve the Matiran mystery?

Once upon a time, the only thing that mattered about a picture was what one could see. The idea of a picture as solely a visual object was so pervasive that the first digital cameras went so far as to place a time stamp on the printed photograph. That’s strange, of course, since the data is embedded in the image. But at the time, we still thought of pictures as physical objects.

The date and time of the image, which is stored in the digital file that contains the visual image, is what is known as “meta data.” Metadata is information about the picture that can include the date and time the picture was taken, what sort of camera it was taken with, any settings used, what sort of camera was used, what sort of software processed the image, and where the camera was located when the picture was taken.

The other day, my friend Aaron was running late for a Skype call. He sent me an email saying, “Can’t mess with my happy hour.”

The metadata for Aaron’s photograph included his latitude and longitude. Although the location was a few meters off, using street view images, I could identify that he was sitting at the Le Studio Cafe just off Place du Bourg-de-Four in Geneva, Switzerland. (The picture contains other information – If you look closely, Aaron is sitting with his wife and infant, who is still nursing. Aaron is having a glass of wine, wearing a checked shirt.)

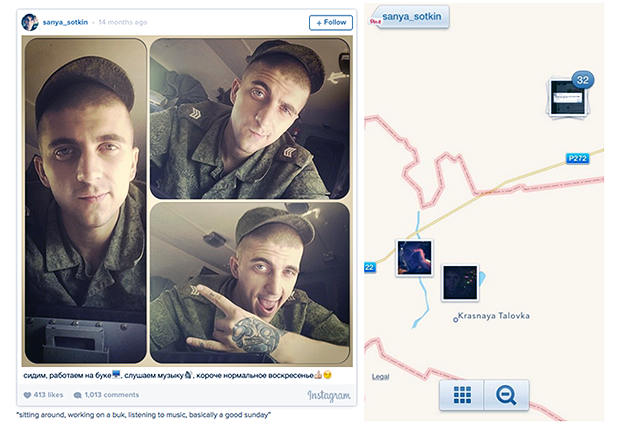

This is funny when your friend is running late. But if you are a Russian solider serving in Ukraine on a deployment that is supposed to be secret? Leaving the metadata in a picture of yourself on deployment can reveal that Moscow is lying about not having combat forces in Ukraine. In fact, the soldier claimed he was working on a Buk surface-to-air missile system – the same type of missile system that downed a Malaysian Air flight, killing all 298 persons aboard.

Time stamps can also be useful. In March 2015, the Iranian Minister of Defense visited a new facility for producing carbon fiber, an important material for centrifuge and missile programs. The Iranians deleted the locational data from the images, although it was easy enough to find the plant. But the Iranians did not delete the time stamps, which revealed two important facts. First, the visit had occurred some months earlier, in December 2014. Second, and more importantly, the time stamps showed the second the picture was taken, which means it was possible to place them in order. Using this information allows one to recreate the walkthrough in the building and model the internal layout of the facility.

Digital images can also be scrutinized for alterations. The Soviet Union and other authoritarian states pioneered the alteration of images. David King, a British graphic designer and avid collector of Soviet art, wrote a book, The Commissar Vanishes: The Falsification of Photographs and Art in Stalin’s Russia, showing images that had been altered by Soviet authorities. It is easier to alter digital images, but perhaps harder to do so without getting caught. New software allows us to examine photographs for possible manipulation by analyzing the information contained in each pixel. Agence-France Presse publishes images from North Korea’s Korean Central News Agency, but has a serious problem – how does it verify that the images aren’t doctored? As a respectable news agency, AFP wants to provide images from North Korea, but it does not want to be a conduit for North Korean propaganda. An image showing North Korean landing craft turned out to have been altered; the North Koreans cut-and-pasted the same landing craft over to make it appear as though they had more than one. AFP detected the forgery using software, called Tungstene, and withdrew the image.

How did metadata help us solve the Matiran mystery?

Metadata turned out to be helpful in determining that the door supposedly at an enrichment facility was really sitting at a warehouse outside of Tehran.

In this case, we were not lucky enough to have the latitude and longitude; the image was apparently taken by a camera without a GPS device, not a cellphone. (Although this, in itself, is telling. Would Iran really let a photographer with a regular camera into its super secret uranium enrichment site?)

In fact there was very little metadata. But what little data there was helped. The metadata on the image of the safe was consistent with that in a series of images on the website and blog of the GMP company. The files were encoded in the same way and the same software had been used to process them. While this was far from definitive, the metadata was consistent with the assumption that the images were part of the same set of images. This linked the images on the company’s website to the image of the safe and other images posted on a blog maintained by the firm.

The fact that the images appeared to be part of the same set helped encourage us to match the external and internal images of the site – a process that can generate high confidence in the match. But it also helped demonstrate the provenance of the image of the door. It was taken as part of a series of promotional images for a company, not surreptitiously by a source seeing an underground nuclear facility.

Next read about Civil Data, and Social Media.

Your are currently on

Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest on nuclear and biological threats.

With the Center for Advanced Defense Studies, NTI demonstrates the viability of using publicly available information and machine learning to detect nuclear proliferation.

Progress on nuclear arms limitation and reduction is at risk, learn more and dismantle a nuclear weapon in augmented reality. (CNS)

The first detailed, exclusively open-source assessment of the five new nuclear weapon systems announced by Russian President Vladimir Putin in 2018