Mimi Hall

Vice President, Communications

Atomic Pulse

Frank Aum is currently a Visiting Scholar at the U.S.-Korea Institute,

Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies. He previously worked as a political appointee

in the Obama administration, serving as the Senior Advisor for North Korea in

the Office of the Secretary of Defense and Special Counsel to the General

Counsel at the Department of the Army.

In 2017, he received the Secretary of Defense Medal for Outstanding

Public Service.

Aum shared his views with Atomic Pulse on the threat posed by North Korea, the status of its nuclear program, and options for the United States. Find NTI’s latest resources on North Korea here.

Before he left office, President Obama

told President-elect Trump that North Korea was the “most urgent problem” he

would face. Why?

North

Korea poses a serious direct threat to the United States, our South Korean and

Japanese allies, and our forces in the region due to its large conventional

forces, its growing weapons of mass destruction program, its history of

proliferation, and its willingness to flout international law to achieve its

aims.

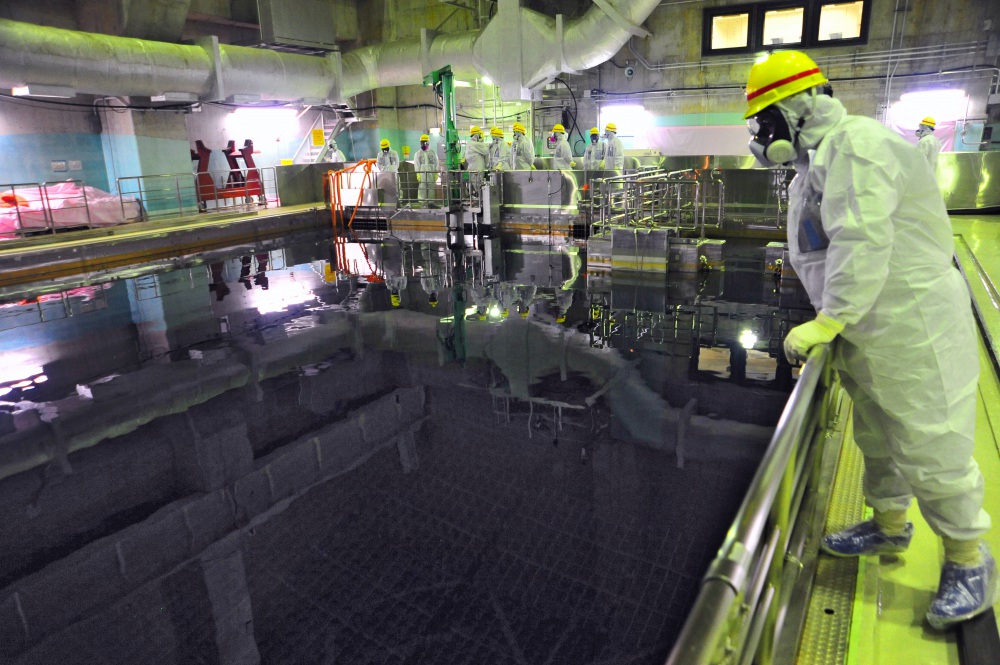

North

Korea is considered to have an advanced and comprehensive nuclear program, with

over 100 nuclear-related facilities. Since 2006, North Korea has conducted five

nuclear tests, and the last one, in September 2016, had an estimated yield of

20 to 30 kilotons. Experts assess that North

Korea currently has enough fissile material and weapons inventory for

approximately 25 nuclear weapons, and in a worst case scenario, could have

up to 100 weapons by 2020.

With

regard to delivery systems, experts estimate that North Korea has at least several

hundred short- and medium-range ballistic missiles that can reach all of South

Korea. North Korea also possesses intermediate-range missiles that can reach

Japan and Guam, and has revealed different variants of mobile ICBM missiles

that can potentially target the continental United States.

Most analysts believe

that North Korea has developed the capability to miniaturize a nuclear warhead

to place on top of most of its missiles, but it’s unclear whether it has also

developed a reentry vehicle that can protect the warhead from the stress of returning

to the atmosphere.

Ultimately, without flight tests of its ICBM, we don’t know for sure about its capabilities. However,

during his New Year’s address this year, Kim Jong-un claimed that the country

was making final preparations for its first long-range missile test.

What options does the United States have

to confront this threat?

We

have bad and worse options. Let me go through some of the options that the

Trump administration has reportedly considered:

On

one end of the spectrum is conducting military strikes, either on North Korea’s

nuclear and missile facilities to degrade its programs or as part of an attempt

at regime change. There are many problems with a military strike, whether done

preventatively or preemptively in self-defense. First, as I mentioned, North

Korea has over 100 related nuclear facilities and perhaps many more in its

network of underground facilities. It also has mobile missile launchers that

can be dispersed from garrisons and hidden quickly. So it would be nearly impossible

to take out its nuclear and missile programs in a clean and comprehensive way,

which allows for the possibility of nuclear retaliation. There is also a strong

likelihood that North Korea would retaliate using conventional means, including

the hundreds of artillery shells that could reach Seoul easily, or even using chemical

and biological weapons. Another complicating factor is that if we are

considering a risky strike, we would need to evacuate thousands of U.S.

citizens from Seoul beforehand, which also tips off North Korea and China about

impending danger. This is why most experts believe that a military strike is

not realistic. Another option might be covert action to degrade North Korea’s

facilities, but all the attendant risks I mentioned before still apply.

On

the other end of the spectrum is to tacitly accept North Korea as a nuclear

weapon state and shift the focus to counter-proliferation, sanctions,

deterrence, and missile defense. The problem here is that North Korea’s nuclear

weapons still remain, as does Pyongyang’s propensity to proliferate material

and technology. Also, there is the concern that Kim Jong-un may escalate conventional

provocations against South Korea, believing that his nuclear program will deter

U.S. intervention. Furthermore, accepting North Korea’s nuclear status may erode

South Korea and Japan’s forbearance, causing them to develop their own indigenous

nuclear weapons to provide strategic balance in the region. This also has

negative implications for the global non-proliferation regime. With regard to

missile defense, our ground-based interceptors in Alaska and California don’t

have a perfect track record in tests for interception of ICBMs, so this isn’t

something we can rely on with high certainty.

In

terms of deterrence, some have suggested that the United States should deploy

nuclear weapons to South Korea. But we already provide extended deterrence

through our conventional forces on the Peninsula as well as extended nuclear

deterrence from off-Peninsula. There may be some messaging or bartering value

by deploying nuclear weapons in South Korea, particularly with regard to China,

but this would be at the cost of undermining the U.S. and South Korean goal of

denuclearizing the Korean Peninsula.

What are the less bad options?

The

current debate among North Korean watchers has centered around two conventional

camps: pressure vs. engagement.

On

one side are those who believe that the United States hasn’t come close to

implementing a full pressure campaign against North Korea using diplomatic

isolation and financial measures. This is true, we didn’t really have a robust sanctions

regime on the level of Iran, Cuba, South Sudan, or Myanmar until just last

year, when Congress passed the North Korea Sanctions and Policy Enhancement Act

and the UN Security Council passed Resolutions 2270 and 2321. It appears that

the Trump administration’s North Korea policy will largely follow this course,

ramping up pressure against North Korea and, indirectly, China. This course could

include more unilateral U.S. sanctions against Chinese banks and other entities

in China that help North Korean front companies conduct prohibited activities. Stronger

enforcement of sanctions, both by the U.S. government and other governments,

would also be helpful.

However,

there are several problems with the pressure approach. First, as the latest United

Nations Panel of Experts report indicated, North Korea has been very good about

adapting to international sanctions, using evasive methods and front companies

to maintain access to the international financial system. These circumvention

methods, as well as inadequate compliance and enforcement by UN Member States, have

undermined the UN resolutions’ impact.

Second,

since a large percentage of North Korean activities and exports go through

China, any successful pressure campaign will require Chinese cooperation and

enforcement. But China has been resistant to clamping down on North Korea too

hard because it doesn’t want to risk regime instability and crisis on its

borders. Also, if you directly sanction Chinese entities, you risk angering

China and jeopardizing cooperation with Beijing on a range of other important

issues.

The

third problem is that it’s not clear what the goal of a pressure campaign is. Targeted

financial measures are a tool or tactic but they are not an end in itself. Some pressure advocates would argue that the

goal of using pressure would be to either have North Korea collapse or to

coerce North Korea to return to the negotiating table to talk sincerely about

denuclearization. But given North Korea’s sanctions evasion and China’s

unwillingness to tighten the vise too hard, I just don’t see either of these

outcomes happening any time soon. In fact, North Korea recently said that the U.S.

cruise missile strikes on Syria on April 6 vindicated its decision to develop

its nuclear program. The bottom line is that pressure can and should be

intensified, but it likely won’t lead to our desired outcome, at least not by

itself.

On

the other side are the advocates of engagement. This side recognizes that

sanctions are an important tool but believe that at some point, there needs to

be a political solution to this crisis that requires talking. The problem here

is that we have been talking to North

Korea, and this is over 25 years, both in terms of official negotiations that

the public is aware of but also as part of confidential talks that the public

is not aware of. When we do talk, North Korea refuses to discuss

denuclearization and instead wants to come to the table as an equal nuclear

power to talk about a peace treaty that would end the Armistice Agreement,

which may entail the removal of U.S. forces from the Korean Peninsula. These

are considered non-starters for the United States.

One

group of engagement proponents have argued for negotiating with North Korea to

achieve a freeze on nuclear and missile tests in exchange for humanitarian aid

and sanctions relief, and then this would be a starting point for discussions

later on related to denuclearization. However, skeptics claim this approach is

disingenuous because even if North Korea were to agree to a freeze, which it

has shown no interest in doing, it has not demonstrated a good track record about

letting international monitors verify the freeze.

In summary,

all of these options are not good. It appears that the Trump administration

will continue to rely on diplomatic isolation, military deterrence, and

financial pressure as its North Korea policy. And the April 6-7 Trump-Xi summit

did nothing to change this expectation. But I hope that, in addition to bigger

sticks, the Trump administration is also considering sweeter carrots – pressure

and engagement don’t have to be mutually exclusive and can sometimes be

mutually reinforcing.

Given the poor choices, what is your

outlook for the future?

Barring

an extreme shift in policy, I think in the future, we will likely be in the

same unresolved situation as today but with greater risk. At some point in the

next several years, North Korea will have demonstrated a potential long-range

ICBM capability, which may cause the United States to consider even riskier options.

Similarly, South Korea and Japan will need to demonstrate to their publics that

they are taking measures to better defend themselves, including offensive

strike capabilities in the case of Japan, and more calls for the deployment of

U.S. nuclear weapons in South Korea.

Perhaps

the most alarming aspect is that even if our policies “succeed” in creating instability

or regime collapse in North Korea, which seems inevitable, then we will face an

incredibly daunting situation in terms of securing the weapons of mass

destruction in North Korea. You not only have all of North Korea’s nuclear material

and facilities – which the Nuclear Threat Initiative’s last Nuclear Security Index rated at the

bottom in terms of theft and sabotage – but you also have the missile

facilities, the chemical and biological weapons program, the potential for

factionalization of the North Korean military, and three countries – China,

U.S., and South Korea – that are all wary about the intervention of the other.

So beyond the current efforts to achieve North Korean denuclearization, there

really needs to be a concerted, sustained, and resourced effort to address this

type of counter-WMD situation in a post-collapse scenario.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest on nuclear and biological threats.

For nuclear power to be a problem solver rather than a problem maker, the international community must push for a smart brand of nuclear power that prioritizes safety and security.

Does a Thorium-based Nuclear Fuel Cycle Offer a Proliferation-Resistant Future? Not Necessarily.

Understanding the Iran Nuclear Agreement: Managing risks in an era of dangerous rhetoric and provocations