Kaegan McGrath

The James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies

On 6 May 2009, the Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States (Commission) released its final report to the President, Congress, and the public at large. Chaired by former Secretary of Defense William J. Perry, and vice-chaired by former Secretary of Defense and Energy James R. Schlesinger, the Commission was tasked with providing a "bipartisan, independent, forward-looking assessment of America's strategic posture." [1]Despite finding consensus on many issues germane to U.S. nuclear strategy, in its final assessment the Commission remained divided upon a topic that has gained substantial traction in the nonproliferation community in recent years—the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT). While about half of the Commission members support the CTBT, including Perry, who testified in favor of the treaty in 1999 when it was rejected by the Senate, Schlesinger and the other half of the Commission members oppose the treaty's ratification; they argue, "passage of the treaty would confer no substantive benefits for the country's nuclear posture and would pose security risks." [2] The Obama administration, as well as many nonproliferation experts, view U.S. ratification as a means to create an international landscape conducive to furthering U.S. international arms control and nonproliferation interests. [3] For example, Chairman Perry argues that demonstrable progress on securing CTBT ratification in the United States would create an environment favorable to achieving a successful outcome at the 2010 Non-Proliferation Treaty Review Conference (2010 RevCon), while failure on moving the test ban closer to ratification could derail attempts to direct attention to proliferation issues of critical U.S. interest. North Korea's most recent proclaimed nuclear test and the nuclear ambitions of an increasingly capable and assertive Iran provide just a glimpse of the host of nonproliferation challenges presently facing the international community.

Renewed interest in the test ban during recent years, particularly following an endorsement by Kissinger and Shultz et al. in the Wall Street Journal, has given this nearly moribund treaty a respite from irrelevancy within U.S. national security circles. [4] Senate consent on CTBT ratification is clearly not a foregone conclusion; two thirds of the Senate must vote in favor of the treaty. Even with 60 Senate Democrats providing their consent to the treaty, at least seven Republicans must also be convinced of the treaty's merits in order to achieve successful ratification. [5] According to Senate sources, the number of Senators now in favor of the CTBT is no more than 63, four short of the 67 needed for Senate consent to the treaty. [6] Arguments raised by the Commission members reflect many of the concerns expressed by skeptics of the test ban treaty during the brief Senate debate in October 1999. For example, the supposed disagreement on the scope of the treaty, doubts about its verifiability, the inability to maintain confidence in the U.S. stockpile under the CTBT, and the treaty's limited contribution to U.S. nonproliferation interests constituted core criticisms of the treaty in 1999, and Commission members relied on these and other objections in their final report. This issue brief provides a concise analysis of the arguments laid out by Commission members opposed to U.S. CTBT ratification, and concludes that none of the assertions contained within the report alter the overall net benefit to U.S. national interests of ratifying the treaty. Many of the claims misrepresent the objectives of the treaty, the negotiating history of the CTBT, and the scientific data available on verification capabilities. Moreover, the Commission was able to agree upon measures that the United States should take in the event that CTBT ratification occurs, such as provisional application of the treaty if entry into force is stalled. The Commission's final report suggests there is an emerging consensus that U.S. ratification is within reach, and opponents of the CTBT are defining terms under which they could accept the test ban.

With its work facilitated by the United States Institute of Peace, the Commission considered the nexus between nonproliferation strategies and U.S. military capabilities, including any role for strategic weapons and other tools (such as missile defense) in countering military threats to the United States and its allies. [7] In its final report, the Commission noted the urgency of reviewing and renewing U.S. nuclear strategy, mainly due to the perils of an international nuclear proliferation "tipping point," as well as "an accumulation of delayed decisions" about the future of the U.S. nuclear weapons complex. [8] The Commission asserted that as long as "nuclear dangers remain," the United States must maintain "a strong deterrent that is effective" in meeting U.S. security needs and those of its allies, though the U.S. deterrent "need not play anything like the central role that it did for decades in U.S. military policy and national security strategy." [9]

Members of the Commission were chosen by House and Senate Arms Services Committees, with selections divided equally between legislators from both sides of the aisle. On the Democratic end of the Commission, members of note in the CTBT context include Perry, Tarter, and Hamilton; Glenn and Halperin have also asserted their support for the treaty in varying degrees. During a press conference, Perry articulated that his support for the CTBT was based on two principles: the treaty's role in reasserting U.S. leadership in preventing nuclear proliferation, and the constraint the test ban put on other countries. [10] Bruce Tarter, then Director of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL), testified before the Senate on October 7, 1999 that LLNL remained positive about prospects for successfully maintaining the U.S. arsenal under the CTBT with the Stockpile Stewardship Program (SSP). Tarter and Hamilton both populated the list of "Prominent Individuals and National Groups in Support of the CTBT" entered into the record during Senate hearings in 1999. [11] Foster, Woolsey, and Schlesinger, selected by Republican Congress members, have all weighed in significantly on the CTBT in the past as well. John Foster, Director Emeritus of LLNL, testified to Congress in 1999 that without the ability to perform nuclear weapon tests, the reliability and safety of the U.S. stockpile will degrade. James Woolsey, Director of the Central Intelligence Agency under President Clinton, came out against the CTBT in 1999, and Vice-Chairman Schlesinger has opposed the CTBT maintaining that there are only modest benefits to be gained through U.S. ratification. According to Perry, many of the Commission members who oppose CTBT ratification will likely be testifying against the treaty during any Senate re-review. [12]

First, there is no demonstrated linkage between the absence of U.S. testing and non-proliferation. Indeed, South Africa and several other countries gave up nuclear weapons when the United States was testing, while India, Pakistan and North Korea proceeded with nuclear weapons programs after we ceased. Ratification would not dampen North Korea's or Iran's nuclear programs, and the CTBT would not prevent other countries from developing basic nuclear weapons because testing is unnecessary."

The authors' assertion that there is no demonstrated linkage between the absence of U.S. testing and nonproliferation is problematic, and clarity on a few issues is essential. The linkage between U.S. testing and nonproliferation must be assessed not only from the standpoint of horizontal proliferation of nuclear weapons and related technologies to more states, but vertical proliferation — the increase in size, quality or destructive capacity of a given state's nuclear arsenal. [13] The CTBT was never expected to prevent the development of basic nuclear weapons; the gun-type nuclear weapon dropped on Hiroshima was never tested. The test ban's contribution to non-proliferation is the constraint it imposes on the development of advanced nuclear weapons. Though history has demonstrated the difficulties of limiting horizontal proliferation, the CTBT would place a severe constraint on the vertical proliferation of advanced nuclear weapons in states with either extensive or limited testing experience. Only a handful of nations possess MIRVed thermonuclear devices, and the highly sought after sea-based version of these weapons. [14] Were there a critical breakdown in the non-testing norm, these highly destructive weapons would certainly proliferate. A legally codified test ban would decrease the risk that this breakdown could occur.

With regard to the impact of U.S. testing on decision makers in states of proliferation concern, every country cited by the authors, whether giving up their arsenals or proceeding with nuclear weapons programs, made the decision to pursue nuclear weapon capabilities while the United States was testing. South Africa, as well as some of the Newly Independent States (NIS) left with a Cold-War legacy arsenal after the Soviet breakup, gave up their nuclear weapons not only as a result of complicated domestic and international diplomatic pressures, but also due to the increased internalization of nonproliferation obligations as the mainstream norm. Pretoria was concerned with establishing friendly relations with the international community, as were the NIS, and participation in the international nonproliferation regime was a key factor in attaining this objective. The strength of the non-testing norm is evident through the ease at which the United Nations Security Council has issued resolutions condemning the tests conducted on the Korean peninsula in the past three years, as well as in South Asia in 1998. The current United Nations sanctions against the DPRK for its most recent nuclear test include a ban on exports of all military equipment and imports of all weapons excluding small arms, and contain a provision calling on states carry out inspections on DPRK ships in order to ensure compliance with the resolution. [15]

Finding P-5 consensus on a tough sanctions resolution against the DPRK at the UNSC is an arduous task, as China and Russia consistently prefer to embrace diplomatic measures rather than approve harsh sanctions. The CTBT serves to vitally reinforce the non-testing norm, and thus enhances the maneuverability of the international community in responding to rogue challenges to that well established norm. Moreover, North Korea declared its intention to develop and test nuclear weapons, while the objective of the test ban is to prevent the clandestine development and improvement of nuclear weapons. To be sure, the CTBT alone could not solve the nuclear issue on the Korean peninsula, and similarly, the treaty cannot prevent Iran from breaking out of the NPT and overtly pursuing a weapons program. [16] However, the CTBT and its verification mechanism would dampen attempts by North Korea or Iran to obtain nuclear weapon capabilities through clandestine testing programs.

"Second, the United States would follow the letter of CTBT restrictions, although the treaty is unlikely ever to take effect. Entry into force would require many other countries to sign and ratify, including North Korea, Iran, Pakistan, India, China, Israel, and Egypt—the probability of which is near zero. Consequently, the U.S. would be bound by restrictions that other key countries could ignore."

The United States would follow the letter of CTBT restrictions whether the test ban were in effect or not; the U.S. has maintained a moratorium on all nuclear explosive testing since October 1992, and there is no indication that this moratorium will be lifted in the future, barring any systemic failure of confidence in the stockpile. [17] The United States is a state signatory to the CTBT, and therefore remains committed not to act against the purpose of the treaty according to customary international law. Accordingly, plans to transform the U.S. nuclear weapons complex incorporate designs suitable for a smaller, more efficient overall complex with fewer weapons, consolidated sites and materials, and more responsive capabilities, which would ensure the long-term safety, security, and reliability of the stockpile while reducing the likelihood that the United States would have to return to nuclear testing. [18] To be sure, the United States has no intention to resume nuclear testing in the foreseeable future. However, if an inordinate amount of time passes without the CTBT entering into force, or being applied provisionally, and nuclear experts conclude that testing would be required in order to ensure the safety, security and reliability of the U.S. stockpile, the United States would have more legitimate rationale for abrogating the treaty and resuming nuclear testing.

Although maintaining that the treaty is held up in the domestic legislative process, China has consistently supported the CTBT, hosts auxiliary stations, and has actively participated in the development of the IMS. [19] Although a Chinese ratification is not guaranteed if the United States ratifies, it appears that China will not proceed with the ratification process unless Washington moves first. The Israeli position on the CTBT remains highly supportive, and U.S. pressure could feasibly convince opponents of the CTBT in Israel that the country has more to gain than lose from accepting the test ban. Disputes remain between Israel and several Middle Eastern countries, most prominently Iran, over Israel's designation in the Middle East and South Asia regional grouping in the treaty's text. [20] However, the Israeli government has no interest in testing a nuclear device, as doing so would produce a shockwave in the region with disastrous implications for regional stability and the international nonproliferation regime. Following the possible ratification by the remaining nuclear weapon states (NWS) under the NPT — the United States and China — Israeli ratification of the CTBT could ameliorate Egypt's concerns with the treaty. Though Egypt's situation poses some very significant challenges, Indonesia has stated that it would ratify the CTBT after the United States, and an outcome at the 2010 Review Conference deemed successful by the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) could put Egypt under increased international pressure to move forward on the test ban. [21] The political complexities in South Asia dictate that seeking approval of a legal ban on nuclear testing from both India and Pakistan requires patience as well as diligence. Nonetheless, with China and the United States having ratified, New Delhi would again be under more intense pressure, and recent elections in India signal a shift away from highly nationalistic and divisive political ideologies evinced by the election of more moderate and reform minded candidates. [22] India has previously stated that it would not block the entry into force of the CTBT, and Pakistan, for its part, has stated in the past that it is ready to sign and ratify the CTBT if India takes the lead. [23] Along with New Delhi, Tehran remained opposed to the treaty as it stood in the CD in 1996, but has since signed the CTBT and has voiced its support for the treaty's objectives at various international venues. The CTBTO already has certified a primary seismic station in Tehran, and two auxiliary stations are currently in the testing phase in Kerman and Shsuhtar. [24] Accepting the test ban treaty would present an opportunity for Iran to further assert that its nuclear program is entirely peaceful in nature. Although it is the mandate of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) to resolve issues related to the up-stream elements of any nuclear weapons program, the CTBTO would provide invaluable assistance in monitoring any down-stream activity in Iran, i.e., a clandestine nuclear test. Furthermore, whether Iran decides to ratify the CTBT or not, continuing improvements in monitoring capability, possible through the development of the IMS, could allow for the provision of additional information on a possible clandestine Iranian nuclear test to the IAEA, with which the Agency could ask for a special inspection, even under its current mandate and the absence of the Additional Protocol in Iran. Therefore, there would be no significant security benefit or otherwise of withholding CTBT ratification in Tehran, as doing so would not reduce the likelihood that a clandestine test would be detected by the IMS and national means of verification.

The successful denuclearization of the Korean peninsula poses immense challenges to the international community, as well as to the credibility of the nonproliferation regime. However, similar to resolving the issue of DPRKs formal status vis-à-vis the NPT, North Korea's signature and ratification of the CTBT need not be precluded from any reasonable agreement involving a roll back of DPRK nuclear capabilities and an easing of tensions in the region. [25] As the norm of non-testing strengthens and the treaty gains more ratifications, Pyongyang will find itself more and more isolated from the international community if it continues to reject participation in the nonproliferation regime, including the CTBT. In this case, Beijing may feel more compelled to pressure the reclusive regime into reintegrating itself back into the international community, and reestablishing itself in the architecture of the nonproliferation regime. Although the likelihood of such a desirable outcome is debatable, it is also difficult to assume a near zero probability. Moreover, in the event that the DPRK, or any other Annex II State for that matter, withholds ratification and effectively casts a single veto on the treaty, there are numerous arguments in favor of a provisional application of the treaty pending entry into force or an amendment by the ratifying states of the entry into force requirements. [26]

Third, the treaty remarkably does not define a nuclear test. In practice this allows different interpretations of its prohibitions and asymmetrical restrictions. The strict U.S. interpretation precludes tests that produce nuclear yield. However, other countries with different interpretations could conduct tests with hundreds of tons of nuclear yield—allowing them to develop or advance nuclear capabilities with low-yield, enhanced radiation, and electro-magnetic-pulse. Apparently Russia and possibly China are conducting low yield tests. This is quite serious because Russian and Chinese doctrine highlights tactical nuclear warfighting. With no agreed definition, U.S. relative understanding of these capabilities would fall further behind over time and undermine our capability to deter tactical threats against allies."

The negotiations of the CTBT in the Conference on Disarmament between 1994 and 1996 reflected not only an assembly of skilled diplomats jockeying for influence on the final text, but the culmination of decades of preparations by a dedicated scientific and policy community. The events that lead delegates to accept a zero yield test ban without an accompanying definition are complex, and the record clearly shows that all delegates involved with this aspect of the treaty, most importantly China and Russia, understood not only the nature of the treaty's basic obligations, but the implications of ratifying such a treaty. The treaty prohibits nuclear test explosions, and although some states wished to ban all nuclear testing, the United States would not compromise on its demand that the treaty not prohibit nuclear testing that creates no nuclear yield, such as hydrodynamic testing. There were also proposals that would have closed national testing sites (Lop Nor, the Nevada Test Site, Novaya Zemlya, etc.) and disposed of any equipment associated with nuclear testing. In the end, the zero yield test prohibition prevailed, and after imposing a number of safeguards on CTBT approval, including continued nuclear testing at sub critical levels and a "supreme national interests" clause to withdraw from the treaty if nuclear testing is deemed necessary to maintain confidence in the stockpile, the United States signed the treaty. [27]There has been no evidence yet produced that would signal that other countries — Russia and China — hold different interpretations of what exactly is prohibited under the CTBT. Notably, Ambassador Stephen Ledogar testified in 1999 that Russia and China clearly committed themselves to a zero-yield ban. According to Ledogar, this reality is "substantiated by the record of the negotiations at almost any level of technicality (and national security classification) that is desired and permitted." [28] This understanding has also been substantiated by public statements from senior Russian officials as their "position on the question of thresholds evolved and fell into line with the consensus that emerged." [29] Moreover, the testimony of YU.S. Kapralov in the Russian State Duma concerning the issue of the CTBT ratification from January 2000 incontrovertibly supports Ledogar's statement. Kapralov testified that, "qualitative modernization of nuclear weapons" can only be achieved by conducting "actual and hydronuclear tests with any fission energy yield that contradicts the CTBT directly." [30] Furthermore, Kapralov stated that, "there is a danger of concealment of hydronuclear experiments from the verification mechanism of the CTBT," but these issues could be resolved within the framework of the CTBTO verification regime. [31]

These documents, as well as the negotiating record, confirm that the nuclear weapon states fully understood the scope of the treaty being negotiated in Geneva. However, the Commission's assertion that China and Russia are currently conducting nuclear explosive testing in contradiction of the terms of the treaty is a serious claim. Although Schlesinger has referenced "clear intelligence information that others are engaged in activities that we ourselves would not engage in, under the existing rules," Arms Control Association Executive Director Daryl Kimball stated that reports about low-yield testing are "old, not definitive, and technically flawed." [32] Therefore, while it seems clear that the authors' objective is to put forth the perception that as the United States would observe the zero-yield ban other countries could improve their warfighting capabilities with hyodronuclear testing, not only is it unclear whether these assertions are based on hard evidence, but it is even questionable how far low-yield nuclear devices would confer any substantial military advantage to an adversary. [33]

If Russia and China are determined to conduct low yield nuclear testing at the risk of detection and attribution, without a legally codified test ban, the United States has few options to respond to these types of activities. However, the CTBT and it global verification system augment the nuclear detection capabilities of the United States and its allies, as well as provide for the potential for on-site-inspections upon entry into force — an activity unthinkable without the provisions of the CTBT. If these states are "apparently" conducting tests that could contribute to the development of new or improved nuclear warfighting capabilities, the United States must assess whether these improvements mark a significant shift in the strategic balance that necessitates further action. The CTBT and its global verification system would provide the United States with more tools with which to ensure these types of activities were not occurring unnoticed.

"Fourth, the CTBT's problems cannot be fixed by an agreement that all parties follow a zero-yield prohibition because it would be wholly unverifiable. Countries could still undertake significant undetected testing. The National Academy of Sciences concluded that underground nuclear explosions with yields up to 1 or 2 kilotons may be hidden. Consequently, even a "zero-yield" CTBT could not prevent countries from testing to develop new nuclear warfighting capabilities or improve existing capabilities."

It is well understood that with present capabilities absolute verification of a global zero-yield prohibition is an impossible venture; certain hydronuclear test explosions release yields of several tons. However, it is important to recognize that the technical rationale for the zero yield ban, as opposed to a given threshold, is that monitoring for a certain yield would invite arguments over how precisely the yield could be determined. Thus, the qualitative prohibition of nuclear explosions provides an easier verification determinant than a quantitative ban on nuclear explosions above a certain yield. Although the IMS is demonstrably more sensitive today, the negotiators of the treaty envisioned in 1996 a detection system that could detect with high confidence anywhere in the world explosions down to a non-evasive 1-kiloton yield test. [34] The reference to the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is based on a report released in 2002 on technical issues related to the test ban and is considered the preeminent scholarly literature on the matter. The assertion that NAS concluded yields of 1 or 2 kilotons could be hidden underground is accurate, but ignores several factors, including the difficulty of successfully decoupling an explosion and concealing test preparations. [35] Furthermore, the NAS committee concluded that with regard to clandestine testing, additional tests by sophisticated weapon states would do little to add to the threats they already pose to the United States, and countries of lesser experience would not have the ability to master nuclear weapons while concealing the required tests and yields. According to the NAS study, the worst-case scenario threats posed to the United States without a CTBT — sophisticated nuclear weapons in the hands of many more adversaries — are far more dangerous than those posed under a CTBT regime. [36] Therefore, although low-yield testing could be performed in theory while avoiding detection, the military benefits to be gained from testing would be minor, and the substantial risk of detection would likely provide a deterrent effect. [37] The CTBT monitoring system, as well as national technical means of verification, provides the means to effectively verify the treaty, where any significant violation, or combination of lesser violations, of the treaty's provisions will be detected within sufficient time to deny the violator the benefit of cheating. [38]

"Fifth, the CTBT's on-site verification provisions cannot fix these problems. Instead, they seem designed to preclude the possibility of inspections by requiring the approval of 30 members of the Executive Council when only 10 of its 51 members would be from North America and Western Europe. Worse yet, the CTBT allows each country to declare numerous sites with a total of 50 square kilometers out of bounds to on-site inspection."

The composition of the CTBTO Executive Council was also another heavily contested issue during the negotiations in Geneva, as this body was granted the authority to approve an on-site-inspection in the case of possible treaty non-compliance. [39] Though the United States favored the "red light" approach which would have required a number of member states issue an objection to a proposed inspection, should the treaty's "green light" approval mechanism and a geographically diverse council be expected to stymie efforts to verify compliance with a global nuclear test ban? Would member states from North America and Western Europe be the only states interested in verifying whether Russia or China are violating the terms of the treaty?

In the unlikely scenario that Iran or North Korea clandestinely test nuclear weapons while party to the CTBT and evidence gathered from IMS and NTM would provide ample reason to support an on-site inspection, which neighboring states would stand in the way of an activity designed to gain more information on a possible nuclear weapon test? The non-aligned states, representing nearly seventy percent of the world's population, support Iran's right to peaceful energy in varying degrees, but would not ignore evidence that Iran pursued a clandestine nuclear program and tested a weapon. Moreover, by the authors' own standards, North American and Western European representation at the IAEA Board of Governors is even more limited than would be that of the Executive Council. Because two-thirds majority is required for most decisions at the Board of Governors, the consent of a larger percentage of states in other geographical regions is required for a decision at the Board than would be required to approve an on-site inspection at the CTBTO. Does this imply that the United States should abandon the IAEA or cease funding for particular activities? The authors correctly state that countries are permitted to designate sites as restricted-access areas in order to protect sensitive military or industrial information. It is also true that these sites may total up to 50 square kilometers, although it is important to clarify what the treaty actually stipulates. The restricted-access sites may only total 4 square kilometers each, and multiple sites must be separated by 20 meters completely accessible to inspectors. Therefore, though 50 square kilometers throughout the inspected state may be inaccessible, inspectors will always have the ability to conduct inspection activities less than 2 kilometers from any given location within the country. Moreover, inspectors may request access to these sites if they determine that they are unable to fulfill the inspection mandate without access to the sites. To be sure, the inspected state has no obligation to grant such a request, but inspectors will provide details on the request and any other information and report to the Executive Council for further action if no resolution presents itself. [40]

"Sixth, maintaining a safe, reliable nuclear stockpile in the absence of testing entails real technical risks that cannot be eliminated by even the most sophisticated science-based program because full validation of these programs is likely to require testing over time. With nuclear arms reductions our confidence in each weapon becomes paramount, but CTBT ratification would foreclose means to that confidence."

The real technical risks of maintaining a safe, reliable nuclear stockpile were understood at the time of the drafting of the CTBT, which led the Clinton Administration to develop specific safeguards to ensure that the United States could maintain confidence in its stockpile under a test ban. However, the implementation and continued development of the Stockpile Stewardship Program (SSP) has provided scientists with a better understanding of physics of nuclear weapons, particularly the effects of self-irradiation damage on of plutonium alloys used in U.S. nuclear weapon pits. [41] For example, a JASON review of a 5-year LANL and LLNL program to evaluate pit lifetimes concluded that, "most primary types have credible minimum lifetimes in excess of 100 years as regards aging of plutonium." [42] The laboratory community is confident in the capabilities of the SSP, although there are still capacity issues that must be resolved. [43] The Reliable Replacement Warhead (RRW) and subsequent extension and refurbishment programs are all based on the potential development and deployment of these systems while under the U.S. test moratorium. That the United States has the means to consider such options as the RRW is a direct result of the successes of the SSP, which contribute to maintaining confidence in the U.S. stockpile in the absence of explosive testing. [44] Though CTBT ratification denies U.S. nuclear scientists the option to test, SSP gives the scientists the ability to accurately assess the safety, security, and reliability of the stockpile and proceed appropriately with any recommendations. Article IX of the CTBT provides for the withdrawal from the treaty if a state feels that its supreme national interest has been jeopardized. Therefore, the CTBT does not impose restrictions on the United States that would prevent it from responding to challenges arising in maintaining confidence in the stockpile as numbers continue to decline and the nuclear weapons complex is downsized. One could argue that ratifying the treaty and withdrawing would be too provocative a measure that would have negative consequences overall. Deciding to withdraw from the CTBT would surely send profound signals across the globe, but would not a U.S. return to testing without the CTBT have similar consequences? Russia and China, as well as other states with minimal testing experience, appear to be ready to test if their security situation necessitates the action. [45] The potential weakening of the non-testing norm with resumed U.S. testing is a serious concern and requires thoughtful consideration in advance of any decision to test. However, the authors' assertion that "CTBT ratification would foreclose means to [stockpile] confidence" is misleading as the United States is currently better equipped to monitor the stockpile for problems than it was when the CTBT was negotiated. Furthermore, ratifying the CTBT would not foreclose the means with which to deal with a possible breakdown in the confidence of the stockpile. Treaties can be abrogated if national security interests are deemed to be in jeopardy, as evinced by the U.S. withdrawal from the Anti-Ballistic Missile treaty.

Although the Commission remained divided on the test ban, the panel nonetheless made specific recommendations for 1) preparing for the Senate re-review by compiling a net cost/benefit risk assessment, securing P-5 agreement on defining the provisions of the treaty, establishing a diplomatic strategy for securing entry into force, and providing the necessary safeguards budget; and 2) securing P-5 agreement on provisional application of the treaty and accompanying on-site-inspections in the event that the U.S. ratifies the CTBT and its entry into force remains delayed.[46] The fact that the Commission could not agree to support CTBT ratification, yet made specific recommendations on the course of action that the United States should adopt in seeking Senate consent, as well as measures to implement the CTBT verification mechanism in the case that the Senate does provide its consent, illustrates the high salience of the test ban in recent months. The Senate fight over CTBT ratification will be fraught with political posturing, ideological platitudes, and intense lobbying from across the political spectrum. However, current trends indicate that opponents of the CTBT are gradually accepting that U.S. ratification may become a reality, and are therefore outlining terms for which they would consent to the treaty. For example, with regard to the claimed disagreement over the provisions of the treaty, Schlesinger stated that, "Many of the members of the commission would strongly support the CTBT if there were clarification of those rules." The supporters of the CTBT need to identify those members of the Senate who may share similar views on the treaty, and work towards outlining an overall strategy that would ameliorate concerns over U.S. ratification.

Sources:

[1] William J. Perry, Chairman, & James R. Schlesinger, Vice-chairman, "America's Strategic Posture: The Final Report of the Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States (Final Report)," The United States Institute for Peace

[2] Perry, Final Report.

[3] See Daryl Kimball, "The Enduring Value of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty and New Prospects for Entry Into Force," CTBTO Spectrum, Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization, September 2008; and "Nuclear Weapons in 21st Century U.S. National Security" (AAAS), Report by a Joint Working Group of AAAS, the American Physical Society, and the Center for Strategic and International Studies, December 2008.

[4] George Shultz, William Perry, Henry Kissinger, and Sam Nunn, "A World Free of Nuclear Weapons," Wall Street Journal, January 4, 2007, p. 15, https://online.wsj.com.

[5] Sean Dunlop and Jean du Preez, "The United States and the CTBT: Renewed Hope or Politics as Usual?" Issue Brief, Nuclear Threat Initiative, February 2009, www.nti.org.

[6] "The Test Ban Treaty" [Editorial], New York Times, New York, N.Y., May 25, 2009. p. A.18.

[7] "The Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United STATES: About the Commission," The United States Institute for Peace, www.usip.org.

[8] Perry, Final Report.

[9] Perry, Final Report.

[10] Elaine M. Grossman, "Strategic Posture Panel Reveals Split Over Nuclear Test Pact Ratification," Global Security Newswire, Thursday, May 7, 2009, www.globalsecuritynewswire.org.

[11] "Prominent Republicans and Democrats call for CTBT ratification," Test Ban New, White House Working Group on the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty, available at Federation of American Scientists, www.fas.org.

[12] William J. Perry, United States Institute of Peace Press Conference for the Congressional Commission on the Final Report of the Strategic Posture of the United States, May 6, 2009.

[13] CTBTO, Glossary, www.ctbt.org.

[14] See James Clay Moltz, "Global Submarine Proliferation: Emerging Trends and Problems," Issue Brief, Nuclear Threat Initiative, March 2006, www.nti.org; and The Submarine Proliferation Database, Nuclear Threat Initiative, December 2008, www.nti.org.

[15] Ewen MacAskill, "UN approves 'unprecedented' sanctions against North Korea over nuclear test," The Guardian, 12 June 2009, www.guardian.co.uk.

[16] See Michael O'Hanlon, "Resurrecting the Test-Ban Treaty," Survival, vol. 50 no. 1, February-March 2008, pp. 119-132; and Robert Nelson, "3 reasons why the U.S. Senate should ratify the test ban treaty," Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, March/April 2009.

[17] Daryl G. Kimball, "The Logic of the Test Ban Treaty," Arms Control Today, Arms Control Association, March 2009, www.armscontrol.org.

[18] Final Complex Transformation Supplemental Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement Summary, National Nuclear Security Administration U.S. Department of Energy October 2008, www.complextransformationspeis.com.

[19] See "China's position on CTBT," Permanent Mission of the People's Republic of China to the United Nations and other International Organizations in Vienna, June 2, 2004.

[20] Kaegan McGrath, "Entry into Force of the CTBT: All Roads Lead to Washington," Nuclear Threat Initiative, April 2008, www.nti.org.

[21] "Indonesia Vows to Ratify CTBT After U.S.," Global Security Newswire, National Journal Group, Tuesday, June 9, 2009, https://gsn.nti.org.

[22] James Lamont, "India poll triumph is mandate for change," Financial Times, May 16, 2009, www.ft.com.

[23] Bruno Stagno Ugarte, Minister for Foreign Affairs, Costa Rica, statement to the Conference on Facilitating the Entry into Force of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty, 17 September 2007, www.ctbto.org.

[24] Preparatory Commission for the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO), www.ctbto.org.

[25] Jaap Ramaker, Special Representative to the CTBTO, Conference on Facilitating the Entry into Force of the Comprehensive Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty, Vienna, 17-18 September 2007, www.ctbto.org.

[26] See "Chapter 9: Securing the CTBT," in Rebecca Johnson, Unfinished Business: the Negotiation of the CTBT and the End of Nuclear Testing, United Nations, United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research, April 2009.

[27] See Statement by Ambassador Stephen J. Ledogar (Ret.), Chief U.S. Negotiator of the CTBT, Prepared for the Senate Foreign Relations Committee Hearing on the CTBT, October 7, 1999; Keith A. Hansen, The Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty: An Insider's Perspective, Stanford University Press, 2006; and 1993-1996: Treaty negotiations, CTBTO, www.ctbto.org.

[28] Statement by Ambassador Stephen J. Ledogar (Ret.).

[29] Ibid.

[30] Thesis for the testimony of YU.S. Kapralov in the Russian State Duma on the issue of the CTBT ratification (Translated by Nikita Perfilyev), January 2000.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Elaine M. Grossman, "Strategic Posture Panel Reveals Split Over Nuclear Test Pact Ratification," Global Security Newswire, Thursday, May 7, 2009, www.globalsecuritynewswire.org, and "Kimball and Rademaker Debate the CTBT at CSIS", video at www.armscontrol.org.

[33] See Sidney D. Drell and James E. Goodby, "What Are Nuclear Weapons For? Recommendations for Restructuring U.S. Strategic Nuclear Forces," Arms Control Association, October 2007. For more information on low-yield nuclear testing, see Raymond Jeanloz, "Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty and U.S. Security," Reykjavik Revisited, Hoover Institution, 2008; and "Technical Issues Related to the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty," Committee on Technical Issues Related to Ratification of the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, National Academy of Sciences, National Academy Press, Washington D.C., 2002. For more information on Russian and Chinese doctrine, see Anthony H. Cordesman and Martin Kleiber, Chinese Military Modernization: force Development and Strategic Capabilities, The CSIS Press, Center for Strategic and International Studies, Washington, D.C., 2007; and Cristina Hansell and William C. Potter, eds., "Engaging China and Russia on Nuclear Disarmament," Occasional Paper No. 15, The James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, April 2009.

[34] David Hafemeister, "Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty: Effectively Verifiable," Arms Control Today, Volume 38, Number 8, October 2008.

[35] Ibid.

[36] NAS

[37] Hans M. Kristensen and Ivan Oelrich, "Lots of Hedging, Little Leading: An Analysis of the Congressional Strategic Posture Commission Report," Arms Control Today, Arms Control Association, June 2009, www.armscontrol.org.

[38] David Hafemeister, "Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty: Effectively Verifiable."

[39] See Keith A. Hansen, The Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty: An Insider's Perspective; 1993-1996: Treaty negotiations, CTBTO, www.ctbto.org; and Rebecca Johnson, Unfinished Business: the Negotiation of the CTBT and the End of Nuclear Testing, United Nations, United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research, April 2009.

[40] Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty, www.ctbto.org.

[41] "The United States Nuclear Weapons Program: The Role of the Reliable Replacement Warhead," American Association for the Advancement of Science, Center for Science, Technology and Security Policy, Washington, DC, April 2007.

[42] R.J. Hemley et al., "Pit Lifetime," The MITRE Corporation, JASON Program Office, January 11, 2007.

[43] See Bruce T. Goodwin, Glenn L. Mara, "Stewarding a Reduced Stockpile," AAAS Technical Issues Workshop, Washington, DC, United States, April 24, 2008.

[44] Raymond Jeanloz, "Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty and U.S. Security," Reykjavik Revisited, Hoover Institution, 2008.

[45] Richard L. Garwin, "Draft Testimony to the Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States, 9 January 2009, www.fas.org.

[46] Perry, "Final Report."

Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest on nuclear and biological threats.

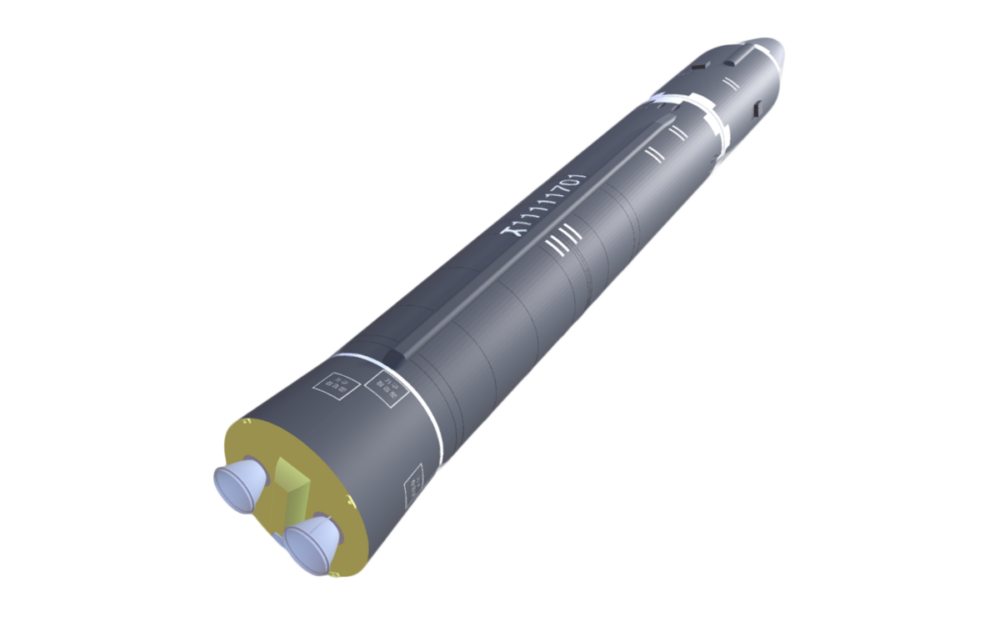

A collection of missile tests including the date, time, missile name, launch agency, facility name, and test outcome.

Christopher Nolan's Oppenheimer is the most high-profile film about nuclear weapons ever made.