Sam Nunn

Co-Founder and Co-Chair, NTI

Thank you, Jim Rogers, for your introduction and for your outstanding leadership. I particularly want to thank Jim and all gathered here today for the work of this Society – helping the world benefit from the peaceful uses of nuclear science.

On this Veterans Day, I would also like to recognize one of our nation’s most outstanding public servants and veterans, former Senator Pete Domenici.

I am delighted to join George Shultz, who addresses every challenge with energy, optimism, keen intellect and wisdom. He is always looking to the future – with one exception. When George attended Henry Kissinger’s 90th birthday party, he reflected, “Ah, Henry — to be 90 again!” I also thank Sid Drell for proving many times that a brilliant theoretical physicist can make a profound empirical difference in the security of his country and the world.

All Americans should be grateful for the remarkable work that the people in this room have done to improve and ensure safety and efficiency in the nuclear field. Preventing accidents is absolutely essential. The future of nuclear energy depends equally on security: preventing the theft of weapons-usable materials—either highly enriched uranium or separated plutonium—that could lead to a terrorist nuclear attack. Nuclear energy also depends on avoiding a dangerous future where a state acquires technology for peaceful purposes, then uses it for nuclear weapons. Safety, security and nonproliferation are the three key links in the chain to assure the benefits of the atom for humanity.

Two Steps for Greater Security

In January of 2007, George Shultz, Henry Kissinger, Bill Perry and I published an opinion piece in the Wall Street Journal. We called for reversing reliance on nuclear weapons globally as a vital contribution to preventing their proliferation into potentially dangerous hands, and ultimately ending them as a threat to the world. We are not the first to express the goal of ultimately eliminating nuclear weapons from the face of the earth. We follow several American presidents, including Reagan and Kennedy on this path. Jim Rogers would call this “cathedral thinking”.

In fact, for more than 40 years, the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, signed by 189 nations and supported by every U.S. president since 1968, has enshrined the obligation of moving toward a world without nuclear weapons. However, the NPT, for all of its virtues and benefits to mankind, offers this goal without a path and without benchmarks. It declares the vision without the steps for getting there. That’s why, in our Wall Street Journal piece, we went beyond the goal by outlining the practical steps required to reach the goal. We recognized that without the vision of a world without nuclear weapons, the steps will not be perceived as fair or urgent, particularly by nations without nuclear weapons. But just as important, without the steps, the vision will not be perceived as realistic or possible.

The Non-Proliferation Treaty also leaves several other dangerous gaps. It declares what many interpret as an unrestricted, sovereign right to nuclear technology for peaceful purposes. But this happens to be the same technology that can lead to weapons that can destroy God’s universe.

When the Treaty was negotiated in 1968, the acquisition of fuel cycle technology and know-how was presumed to be beyond the reach of all but a few countries, and it was believed that sensitive information related to the nuclear fuel cycle could be protected and contained. This presumption is long gone.

The NPT also fails to address nuclear security, because a terrorist group building a nuclear weapon was considered to be somewhere between unlikely and impossible.

Two of the ten steps we proposed in our original op-ed were particularly designed to begin to fill these large gaps. These steps are essential if the world is to prevent nuclear catastrophe and over time achieve the ultimate objectives of the NPT:

First, we must secure all nuclear weapons and materials globally to the highest possible standards.

Second, we must develop a new and improved approach to managing the risks associated with producing fuel for nuclear power.

First—nuclear materials security.

Today, the elements of a perfect storm are in place around the world: an ample supply of weapons-usable nuclear materials, an expansion of the technical know-how to build a crude nuclear bomb, and the determination of terrorists to do it.

This should be a grave concern for all of us. Terrorists don’t need to go where there is the most material; they are likely to go where the material is most vulnerable. That means the future of the nuclear enterprise, including the future of the nuclear power industry, requires that every link of the nuclear chain be secure—because the catastrophic use of atoms for terrorism will jeopardize the future of atoms for peace.

Perspective is crucial. The enemy of nuclear security is not only complacency; it’s also paralyzing pessimism. The message must go out that on nuclear material security, we are moving forward. Because of the cooperation between the United States, Russia and other nations, the world has made progress in securing weapons-usable nuclear materials. Since 2012, seven states have removed all or most of these materials from their territories. Today, 25 countries possess these materials— that’s half the number of states that had them in 1992. Also, more than a dozen states have recently taken important steps to better secure their nuclear materials and reduce their quantities.

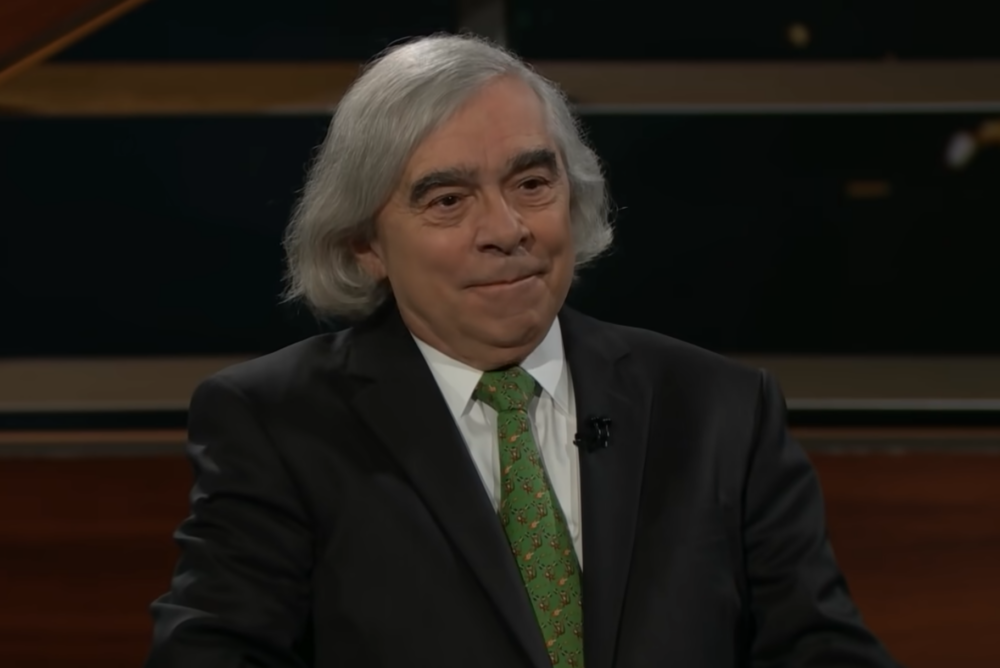

The Department of Energy and Ernie Moniz deserve a lot of credit for this important work. We are fortunate to have an Energy Secretary like Ernie who understands both our energy sector and our security challenges – perhaps better than any other secretary we’ve had.

This security mission, however, is far from complete and, indeed, is a mission that, like safety, never really ends. There are still nearly 2,000 metric tons of weapons-usable nuclear materials spread across the world in hundreds of sites, some of them poorly secured and vulnerable to theft or sale on the black market. A small amount is sufficient to build a terrorist nuclear weapon.

We need to secure all of it to a high standard. Yet, stunningly, even though the destructive power of these materials in dangerous hands has the capacity to shatter world confidence and change society as we know it, there is no effective global system for how it should be secured. Let me repeat that. There is no effective global system for how weapons-usable nuclear materials should be secured.

In spite of the global threat posed by these materials, security practices of countries vary widely. Some states require strong nuclear security practices; others don’t. Some states require strong measures to counter the risk of insider threat; others don’t. Some facilities have armed guards on site; others have to call the police or military to respond and hope that they get there in time.

This is not a complete vacuum. Several important elements for guiding states with their nuclear security practices do currently exist, but they fall far short of what is needed. In particular, the international legal agreement for securing nuclear materials and its 2005 amendment don’t define standards or best practices. Nor do guidelines for nuclear materials security issued by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). Standards imply obligations, but the IAEA guidelines are taken by most states as suggestions and not requirements. In addition, both the legal agreement and the IAEA guidelines cover only 15 percent of weapons-usable nuclear materials — those used in civilian programs. The remaining 85 percent of materials are categorized as military or non-civilian and are not subject even to these limited guidelines.

This lack of an effective global system for nuclear materials security stands in stark contrast to other high-risk global enterprises. For example, in aviation, countries set standards for airline safety and security through the International Civil Aviation Organization, which then audits state implementation of the standards and shares security concerns with member states. If your practices don’t meet these standards, your plane isn’t going to land in the United States, the E.U., China, Russia, Japan, India, Brazil, or most other places around the world.

Obviously, in an age of terrorism, the airline industry depends on this safety and security system for its economic viability, and countries depend on it to protect their citizens. Shouldn’t the security of potentially the most dangerous material on the planet have an equally effective approach?

My bottom line — the world needs a nuclear materials security system in which:

These steps and many others will be demanded by an outraged world after we’ve had a nuclear security catastrophe. I suggest we take these steps now.

Let me turn to the second major challenge—the proliferation of technology to produce weapons-usable nuclear material.

The peaceful applications of nuclear science can play an indispensable role in our efforts to meet human needs in the 21st century. I favor civil nuclear power and believe that it must play a crucial role in our energy future and our environmental future. The promise of our nuclear future depends on how we manage our nuclear present.

As many as three dozen countries are reported to be interested in building their first nuclear power plant. Those who choose to make the nuclear fuel themselves rather than rely on the international market will be technically capable of producing materials for nuclear weapons. As you well know, the same basic technologies used to generate fissile materials for civilian purposes can be used for military purposes. This increases global risks, because the inherently dual-use nature of these facilities provides states with a latent nuclear weapons capability – which, of course, is what’s going on right now in Iran.

While important steps have been taken to strengthen IAEA safeguards and to change the way states conduct nuclear trade, these steps are not enough.

The world has been reluctant to confront this question: Do we really believe that we can live securely in a system that poses so few constraints on any state’s ability to produce weapons-usable nuclear materials?

Iran and North Korea are on the front burner. Both flagrantly violated the NPT by breaching their obligations to put their fuel cycle facilities under safeguards. This question, however, is much broader because enrichment and reprocessing are not illegal per se under the Treaty. Iran, in particular, has been the center of attention these last several days. An agreement with Iran that allows us to test and verify Iran's claim that it has no intention of producing nuclear weapons is absolutely essential. Over the long term, however, we must work globally on new approaches to the fuel cycle, or we will continue to have future Irans and North Koreas, and the world will get increasingly dangerous.

The NPT resulted from an implicit bargain between its member states: Those states with nuclear weapons agreed to give up those weapons over time, in exchange for the states without nuclear weapons agreeing not to acquire them. In addition, the NPT protects the right of all parties to the Treaty to develop, produce and use nuclear technology for peaceful purposes. In fact, currently under the Treaty, any country is free to acquire sensitive fuel cycle technologies and can produce unlimited amounts of these materials for civil purposes. In today’s world, this is a big challenge.

The NPT has been, and will remain, the most important and essential framework for nonproliferation efforts, but unless we work to close its dangerous gaps, neither part of the NPT bargain will likely be fulfilled.

A few questions to consider:

The biggest obstacles are political, not technical. We have to find a path away from the current paralyzing mentality of “haves versus have-not” states and recognize that all states have to make changes for our individual and collective security. Those states that do not have nuclear weapons will no doubt demand that the weapons states move more rapidly to fulfill their end of the bargain—moving step-by-step toward a world without nuclear weapons. They have a point, and this means that both the vision and the steps are essential. Without both moving in parallel, progress on either will be very slow, very difficult, and very uncertain as global nuclear risks increase.

The Issue of Sovereignty

Closing these gaps will not be easy. The roadblock to more effective nuclear materials security and to a more secure nuclear fuel cycle is a concept of national sovereignty that is not consistent with today’s dangers. States opposed to global rules on nuclear security contend that the responsibility for nuclear security within a state resides entirely with that state. Countries resisting changes to managing the nuclear fuel cycle cite their right to enrich and reprocess under the Non-Proliferation Treaty. Most countries with nuclear weapons will not give them up step-by-step unless they’re confident that their build-down will not be met by others building up.

These arguments imply that we must increase nuclear risk to protect a broad definition of nuclear sovereignty. Is that really the case? As I see it, this definition of sovereignty will not survive after the first act of nuclear terrorism. Do we have to wait for such a disaster? The stakes for both global commerce and global stability are very high.

Let me give a vivid example. A couple of years ago, Scientific American magazine reported on a study that investigated the likely impact of a hypothetical regional nuclear war between India and Pakistan using 100 weapons. According to the computer models, more than 20 million people in the two countries could die from the blasts, fires and radioactivity. Smoke from the fires would cover all the continents, diminish sunlight, and shorten growing seasons. Agricultural yields would decline around the world, and one billion people with marginal food supplies could die of starvation within 10 years.

Even if you give this scenario a substantial discount—or even if you change it by assuming a limited terrorist nuclear attack rather than a regional nuclear war—one truth should be clear. The right to do whatever you wish with nuclear technology in your own country is no more compatible with global nuclear safety and security than “do-whatever-you-want” aviation rules would be compatible with safe and secure international air travel.

Fortunately, many countries support the idea of shared and effective responsibility. They understand that this call is not an abdication of sovereignty; it’s an assertion of the prime obligation of a sovereign state – to protect its citizens from disaster. A concern for the fate of citizens in our own countries entitles — even obliges – leaders to insist on global standards for nuclear materials security and a more secure nuclear fuel cycle.

The Tasks and Call to Action

While much of the work in nuclear security is in the hands of governments, it is clear that they need more effective partners outside government. At the Nuclear Threat Initiative:

We acknowledge, however, that NTI is a small, non-profit organization with a limited budget dealing with global threats and global opportunities. The world needs members of the American Nuclear Society to be leaders in the field of security as you have been in safety. Your wisdom and experience are vital to the future of the nuclear enterprise and our security. Yes, government does have the primary responsibility, but you can help. We are in a new era; we must think anew.

In a recent Washington Post op-ed titled “Strategic Terrorism”, former Chief Technology Officer of Microsoft Nathan Myhrvold observed: “Throughout history, each new generation of weapons technology was deadlier and more lethal than its predecessor. More lethal weapons required larger investments and industrial bases. A single nuclear device could destroy an entire city, but it also cost as much as a city and was far more difficult to build.”

Nathan makes it clear that the economics of weapons of mass destruction have radically changed and that today we face a different cost equation and a different world. With today’s technology, a small number of people can obtain incredible destructive power with crude nuclear, biological, chemical or cyber weapons. We must deal with this reality.

I close with this thought: We are in a race between cooperation and catastrophe. We must run faster. With your help and leadership, I am confident that we will.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest on nuclear and biological threats.

The NTI Index is recognized as the premier resource and tool for evaluating global nuclear and radiological security.

“The bottom line is that the countries and areas with the greatest responsibility for protecting the world from a catastrophic act of nuclear terrorism are derelict in their duty,” the 2023 NTI Index reports.

Ernest Moniz says the Russian leader needs to back away from the nuclear button.