Charles B. Curtis

NTI President Emeritus and Emeritus Board Member

It’s an honor to be here again in Moscow at the Russian Academy of Sciences – which has been home for nearly three centuries to distinguished scientists.

Six and a half years ago, we were here in this very hall, called together by the same purpose that brings us here today – to reaffirm the common security interests of Russia and the United States; and to emphasize the special role that scientists play in highlighting nuclear dangers and promoting cooperation.

As everyone in this hall will acknowledge – over the last six years, we did not accomplish all of what we had hoped. We made significant advances in some areas. But in others, we did not do all we set out to do. In the tone of our relations, our two nations ended in a worse place than we began – with a rise in suspicion and a drop in trust.

Today, once again we have two new Presidents.

President Obama is coming off a campaign in which he declared a striking new vision on nuclear weapons – and a different, more collaborative approach to engaging the world. President Medvedev has answered with equally challenging words.

The new nuclear agenda

Here is what President Obama has said.

1. This is the moment to begin the work of seeking the peace of a world without nuclear weapons.

2. We'll work with Russia to take U.S. and Russian ballistic missiles off Cold War prompt launch alert postures, and we will work to dramatically reduce the stockpiles of our nuclear weapons and materials and increase warning and decision time to reduce pressure on the nuclear triggers.

3. We will work to negotiate a verifiable global ban on the production of new nuclear weapons material.

4. We'll set a goal to expand the U.S.-Russian ban on intermediate-range missiles so that the agreement is global.

5. We will lead a global effort to secure all nuclear weapons and material at vulnerable sites within four years.

To match these words with deeds, progress on each of these matters will require the active cooperation of the Russian Federation.

Importantly, this call for a new nuclear agenda is not coming just from the American side.

Russia’s Comments

A few weeks ago, President Medvedev declared, “Today we face an urgent necessity to move on the way to nuclear disarmament. In accordance with its obligations under the Treaty on the Nonproliferation of Nuclear Weapons, Russia is fully committed to the goal of a world free of these most deadly weapons.”

President Medvedev went on to say:

“…I fully share the commitment of the U.S. President Barack H. Obama to the noble goal of saving the world from the nuclear threat and see here a fertile ground for…joint work. I believe that constructive interaction in this field will contribute to general improvement of…Russian-U.S. relations.”

We should all take President Obama and President Medvedev’s words to heart, and we should all recognize the urgency and importance of the task that lies before us.

The stage is set for a “reset” of the U.S.-Russian relationship. A change in direction on nuclear security policy lies at the center of that change. We have a good foundation from which to begin.

Global Initiative and WINS

In 2002, NTI Co-Chairman and former Senator Sam Nunn and Senator Richard Lugar met with Russian officials in the aftermath of the Putin-Bush Summit here in Moscow and proposed a Global Coalition Against Catastrophic Terrorism. Later that year, the G8 created the Global Partnership Against Weapons and Materials of Mass Destruction followed later by the Proliferation Security Initiative and the creation of the Global Initiative to Combat Nuclear Terrorism co-chaired by Russia and the U.S. with over 70 participant states. When the Global Initiative was established in 2006, it called for the sharing of best practices in securing nuclear materials.

The institution that can do that work is called the World Institute for Nuclear Security, or WINS, and it was founded this past fall in Vienna.

As The Economist wrote last October: “WINS is a place where for the first time those with the practical responsibility for looking after nuclear materials – governments, power plant operators, laboratories, universities – can meet to swap ideas and develop best practices.”

We hope that every organization and institution with responsibilities for nuclear materials protection will become a member. If so, WINS can help bring us to the day where the best security practices anywhere are put in practice everywhere. I hope very much that WINS will have the support of the people in this room, and the benefit of enthusiastic Russian involvement. Other initiatives have been taken. But much of our work to reduce nuclear dangers remains to be done.

The Big Opportunity – and the New Politics of Nuclear Security

As everyone in the audience knows, in the first few days of 2007, an opinion piece published in the Wall Street Journal written by former Secretaries of State George Shultz and Henry Kissinger, former defense secretary William Perry, and former Senate Armed Services chairman Sam Nunn noted that “the world is now on a precipice of a new and dangerous nuclear era” and that nuclear deterrence is becoming “increasingly hazardous and decreasingly effective.”

This message, and most importantly, these authors, changed the political debate in the United States, and made it politically possible to talk again of working toward the ultimate goal of a world free of nuclear weapons.

These four individuals – George Shultz, Henry Kissinger, Bill Perry and Sam Nunn – are in Moscow right now, delivering the same message that has dominated their public statements for the last two years: Each of the four has concluded that if we are going to get the cooperation from other states we need to reduce today’s urgent nuclear dangers, we have to re-assert the vision of the world free of nuclear weapons and take the steps that will build trust, reduce nuclear dangers and help develop the foundation for – in President Medvedev’s words – a world free of these most deadly weapons. Russia and the U.S. must lead this step-by-step journey. Undoubtedly, this subject will be prominently on the agenda when Kissinger, Shultz, Perry and Nunn meet with President Medvedev on Friday of this week. I want to emphasize step-by-step the characteristics of this journey.

As we meet here today, we could be on the verge of momentous change. I am fully expecting that our presidents will chart a new course for our two nations when they meet on April 1st on the borders of the G-20 group of states. I believe each president will give instructions on how they wish to “reset” the relationship and change direction. At the same time, the world will be watching and listening to us to see if both sides are prepared to forthrightly recognize and deal constructively with the challenges that “hold us by the sleeve” and impair our bilateral relationship.

Challenges

The major challenges to our bilateral relationship must be addressed if we are to rebuild trust between our two nations and make progress of a new nuclear security agenda. These three are:

• Will the commitment to negotiations bring into effect a START replacement – before December?

• Will our two nations find a path to resolve differences on European Missile Defense?

• Will we be able to develop a new European Security Architecture and find a path to resolve differences on NATO Expansion?

There can be no coherent, effective security strategy to reduce nuclear dangers that does not take into account Russia – its strengths, weaknesses, aims and ambitions. So, it is remarkable – and dangerous – that the United States, Russia and NATO have not developed an answer to one of the most fundamental security questions we face: What is the long-term role for Russia in the EuroAtlantic arc? Whether caused by the absence of vision, a lack of political will, or nostalgia for the Cold War, the failure of both sides to forge a mutually beneficial and durable security relationship marks a collective failure of leadership in Washington, European capitals and Moscow. From his first day in office, President Medvedev has spoken about the need for a new architecture. Now may be the time to begin to give shape to that vision.

To make progress on any of these challenges, we must restore a process of communication and engagement. There can be and will be no progress unless it can pass this test – is it in the collective security interest of both states?

Call to Action/Conclusion

In conclusion, let me say that I am very optimistic about what our two countries can accomplish together in the next few years to reduce nuclear dangers around the world.

I am optimistic, in great part, because of the confidence that I have in the ability of Russian and U.S. scientists to be agents and advocates for change.

This confidence dates back to my service as Undersecretary and Deputy Secretary of Energy in the 1990s. One of the highlights of my time there was seeing the success of the lab-to-lab cooperation between Russian and U.S. scientists, in particular their joint work in the success of the Material Protection, Control and Accounting program (MPC&A)

I have never known work of such significance to go forward more quickly or more harmoniously. In this room are many authors of that successful program. The contracts that launched this cooperation were concluded in six weeks time – and technology, developed jointly by U.S. and Russian scientists, is now protecting HEU and plutonium in facilities across Russia, including at the Kurchatov Institute. Both sides have learned from each other in this experience.

As we have all read, the terrorists that took over the Dubrovka Theater in 2002 when last we met had targeted the Kurchatov Institute before choosing instead to seize hostages at the Theater. Whatever their reasons might have been for avoiding Kurchatov, the fact is, the HEU in the Kurchatov Institute was more secure, and far harder for any terrorist to seize, because of the MPC&A and the cooperation of Russian and U.S. scientists.

The book Dismantling the Cold War explained the MPC&A success this way, and I quote: “Once conceptualized at the lower levels, lab-to-lab programs are then "sold" by each side's scientists to their respective governments. Instead of a U.S. official advocating a program to the Russian government, the recommendation comes from a Russian scientist or Minatom official.”

Clearly, when the trust that the scientists command because of their knowledge is combined with the trust they enjoy because of their patriotism, they have tremendous influence as advisors.

To me, there couldn’t be a better example of the crucial role that scientists can play in advancing our common security. It is more important than ever for our scientists to use the stature they have in the eyes of their country to promote cooperation in reducing nuclear threats.

There have been many periods over the past 60 years of U.S.-Russia relations where time was not ripe for change. This is not one of those times. Many issues are converging – greater danger, a greater sense of urgency, new leadership, the chance of greater trust – and every one of these trends tells us that the moment to push for change is NOW.

As President Obama and President Medvedev have said, Russia and the U.S. should lead the way. But Russia and the U.S. are more likely to lead if Russian and U.S. scientists are pushing from behind. Thank you.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest on nuclear and biological threats.

There is a critical need for a global diplomatic approach to address growing cyber risks, including, where possible, through cooperation between the United States and Russia.

“The bottom line is that the countries and areas with the greatest responsibility for protecting the world from a catastrophic act of nuclear terrorism are derelict in their duty,” the 2023 NTI Index reports.

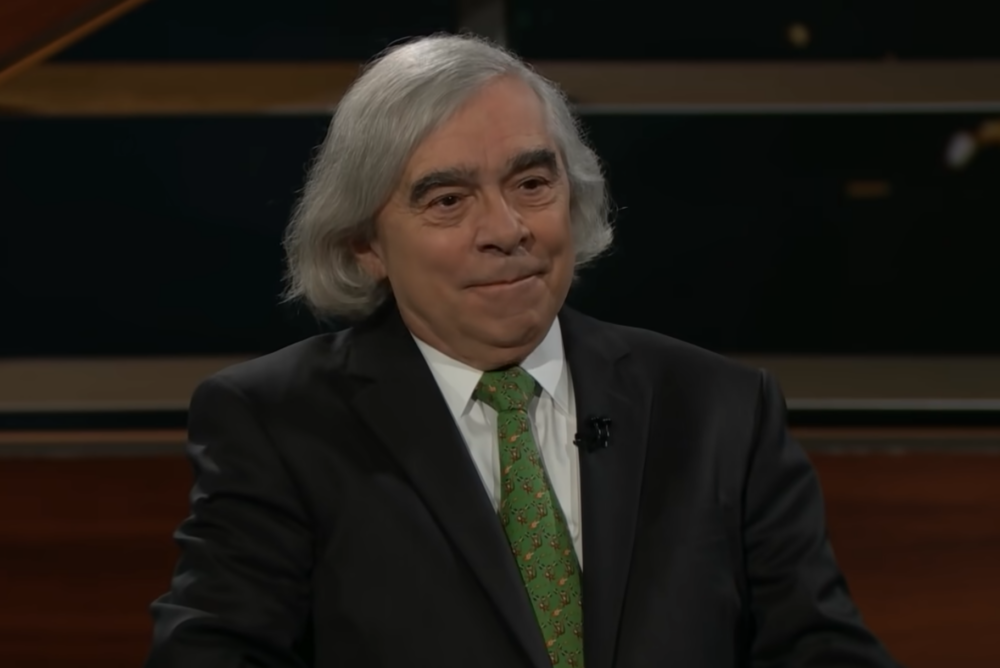

Ernest Moniz says the Russian leader needs to back away from the nuclear button.