Tabitha Sanders

Communications Associate

Atomic Pulse

The

first thing you notice is the silence. Then, the lined faces of the men sitting

before the camera begin to speak in low, hesitant voices. Some avoid eye

contact with the lens.

“I

guess I’m a little perplexed right now,” the first one says softly.

If

the subjects of Morgan Knibbe’s documentary, “The Atomic Soldiers,” seem like wary

participants, it’s because almost all of them are sharing their stories for the

first time.

They

are America’s atomic veterans—the soldiers who were ordered to participate in more

than 200 above-ground nuclear tests conducted between 1945 and 1962, mostly in

the deserts of Nevada and the Marshall Islands. Unlike the scientists who

monitored the explosions from several miles out of range and were equipped with

safety equipment, these men—and they were all men—were placed within range of the

blast.

They

are hardly well-known. Knibbe only discovered the veterans while scrolling

through unclassified nuclear test videos on YouTube when he began to notice

human-like figures wandering across the screen. Curious, he looked further into

the records and learned that at the dawn of the “Atomic age,” the U.S. had

placed thousands of soldiers within the blast zone of its nuclear weapons

tests.

Theories

vary as to why the men were used. Were they guinea pigs for scientists to

measure the effects of a nuclear blast? Was the military preparing its men in

the case of a nuclear explosion on U.S. soil?

It’s

still not clear. For those who sat before Knibbe’s camera, coming to terms with

what they had witnessed was arduous enough.

Atomic testing

The

era of above-ground testing ended late in 1962, and the following year, the

Limited Test Ban Treaty (LTBT) was signed and took effect. By then, hundreds of

thousands of soldiers had been exposed to the above-ground tests. At the time,

they were told never to share or discuss their experiences with anyone, not

even each other. They were warned that doing so might be considered treason.

One of Knibbe’s subjects admits that he did confide in his wife.

It

wasn’t until the late 1990s that the U.S. government officially recognized the

soldiers’ role in the tests with the

Repeal of Nuclear Radiation and Secrecy Agreements Laws in 1996, giving

veterans the freedom to speak about their involvement. Although the men were suddenly

allowed to talk about what they had witnessed, the message was not efficiently

conveyed. By the time Knibbe started reaching out in the mid-2010s, many were

still worried about government reprisal.

Several weeks ago, Knibbe attended a conference for the National Association

of Atomic Veterans (NAAV), where he encountered more than

one veteran still wary of speaking out.

The veterans

On

Sept. 17, Knibbe screened a 15-minute version of his documentary for an

audience at the Nuclear Threat Initiative and took questions about the film and

the veterans. Audience members were stunned to hear the men describe the moment

of the blasts. Without proper protection, they were told to hold their arms

over their eyes, but the flash of light was so powerful that they were able to

see their bones as if looking through an x-ray.

For

many survivors, speaking out about it may be the only way to begin to understand

and process what they had been through. Some detailed the physical toll of the

radiation exposure – from cancerous tumors to memories of the blast that

continue to disrupt their sleep.

“I

think that a lot of us knew that this was not a good thing for us.” one veteran

tells Knibbe in the film.

The

government has taken some steps to atone. Through the Department of Veterans

Affairs, the U.S. will treat those atomic vets who

participated in “radiation-risk activity” and developed “certain cancers” as a

result. Just this year, the Department

of Defense announced that survivors could

apply for the Atomic Veterans Service Certificate. Although estimates vary by source,

the DoD claims that a whopping 550,000 veterans might have been eligible; just

80,000 may still be alive.

A

wider audience?

So,

what’s next for Morgan Knibbe? A screenplay based on The Atomic Soldiers is in its early stages. He teased the project at

NTI, where he conveyed his hope that a more traditionally cinematic approach

might give the veterans a wider audience.

Until

then, the full version of The Atomic

Soldiers can be found on The Atlantic while a 15-minute

cut of the documentary is available on The New York Times.

Morgan

Knibbe is a documentary filmmaker based in Amsterdam.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest on nuclear and biological threats.

"Visiting Hiroshima imparted to me a deep sense of responsibility as well as a renewed energy to work towards a world without nuclear weapons," writes Program Officer Ananya Agustin Malhotra.

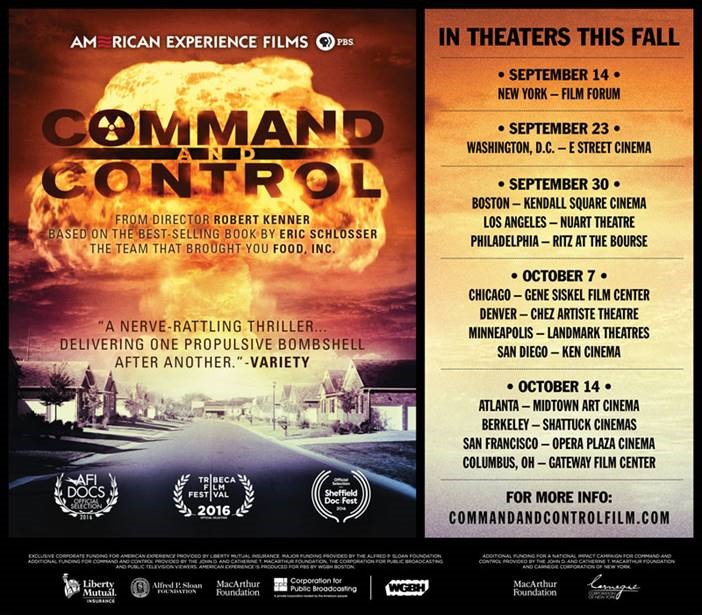

Command and Control to air on PBS in early 2017

There is no noise at first, only a flash so bright that the soldiers see their own bones and blood vessels through their skin, as if they have x-ray vision.