Mimi Hall

Vice President, Communications

Atomic Pulse

Lynn Rusten is NTI’s new Senior Advisor to the Global Nuclear Policy Program. She has held senior positions in the White House, Department of State and Congress, bringing deep expertise in nuclear arms control, nonproliferation, and national security policy. During the Obama administration she served in the State Department and as senior director for arms control and nonproliferation on the White House National Security Council staff.

Following a short consultancy, you joined NTI late last year as senior advisor for global nuclear policy. You’ve got a very extensive background in these issues. So what are you going to be doing at NTI?

I’m going to be advising on the full range of nuclear policy matters and contributing to NTI’s projects in this area. I have a lot of experience in nuclear policy, arms control and nonproliferation, so I expect to be helping with NTI’s work on U.S. nuclear policy, for instance with respect to the Trump Administration’s forthcoming Nuclear Posture Review; the future of the New START Treaty; strategic stability and relations with Russia; how to globalize the reductions process as well as advance verification to support reductions in the future; and more.

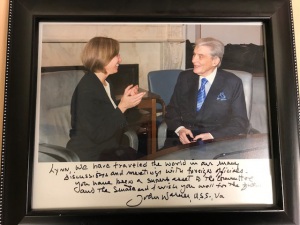

I’m also going to be leading our congressional outreach efforts on Capitol Hill. We already do quite a bit of that, but our leaders – Secretary Moniz and Senator Nunn – are interested in stepping up their engagement with members of Congress and staff to share their perspectives and NTI’s work on reducing nuclear and other WMD threats. NTI is also interested in stimulating greater awareness of these issues on the Hill and encouraging those who wish to take a leadership role in addressing them.

There’s a real lack of understanding around nuclear weapons issues and policy on the Hill, but given the size of the budgets, the consequences of use of these weapons, and the consequences for our military, we need to change that, right?

I think the lack of understanding is reflective of the fact that these issues have not been front and center for the American people or Congress in recent years the way they were during the Cold War when people were very focused on U.S.-Soviet tensions and worried about the potential for nuclear conflict. There were also a lot more treaties that came before the Senate for advise and consent. I think what’s happened over the last couple of decades is that the issues just haven’t been as salient, and as a result, there’s been a real loss of institutional knowledge and memory as members and staff have turned over and haven’t been forced by the legislative agenda or international events to focus as much on these issues.

I think we’re at an inflection point now, though, because of issues like the North Korean nuclear threat and the deterioration of relations with Russia. These issues are gaining more salience so I think we have an opportunity to try to educate members and staff about the policy challenges and also about the tools that are available to address them. And by tools I mean diplomacy, I mean arms control and nonproliferation agreements, I mean the kinds of threat-reduction work that’s been done in the past and how those tools can be applied to different aspects of the problem and in different regions.

When it comes to these kinds of issues, what is the role and responsibility of Congress?

Congress has a very defined role, of course, in matters like treaties where the Senate gives advice and consent. It has a very direct role in matters that require legislation or where legislation has played a role, for instance the sanctions that have been applied to Iran that were used to create the pressure, along with other countries, on Iran to come to the table to negotiate about its nuclear program. Now Congress has a role in upholding the continuation of waivers of those sanctions in exchange for Iran holding up its end of the bargain.

More broadly, although the executive branch has the lead in terms of foreign policy, Congress still has an advisory role. There are oversight hearings, advice to the executive branch, and of course there’s the appropriations and authorization process, and that includes everything from the Defense department and weapons systems to foreign assistance to State department budgets, foreign aid. So these are all aspects of foreign and national security policy where Congress has a role.

Let’s back up for a moment. Tell me a little bit about how you got interested in these issues.

So I’ll date myself by saying that in college I majored in government, but really I was concentrating in international affairs and became very interested in Soviet foreign policy because of a professor who mentored me and taught in that area, and then I ended up going to graduate school where I got a master’s degree in Russian and East European studies. I even studied Russian language at Leningrad State University for a summer, which does date me because of course now it’s called Saint Petersburg

State University.

When I got out of graduate school – this was in the early ’80s at the height of the Nuclear Freeze Movement – I came to Washington. The jobs available if you knew Russian and were in the national security field were either in the intelligence community or Defense department or related to arms control, and I kind of fell into arms control. My first job was at Congressional Research Service, working as a research assistant for a senior fellow who was focusing on U.S.-Soviet arms control.

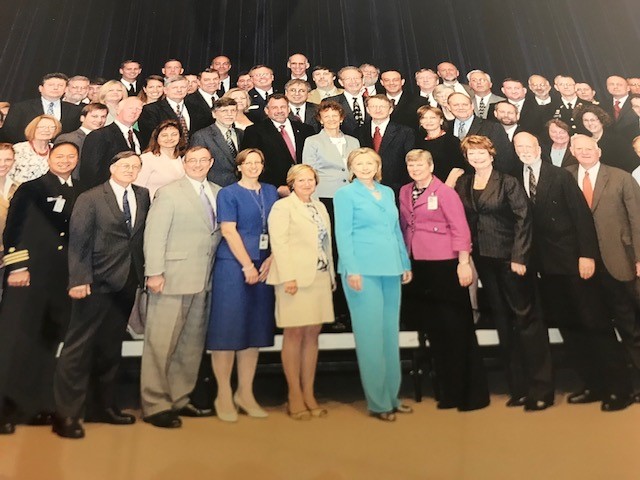

From there I went to the National Academy of Sciences Committee on International Security and Arms Control. This committee was started in a period during the Reagan administration when there were no official arms control talks going on between the United States and the Soviet Union, and this was a committee of very senior scientists who had been involved in the Manhattan Project, former senior-level policy makers, and senior former military. And in fact when I went to work for the committee, (former Defense secretary) Bill Perry was on the committee as was a very young (former Defense secretary) Ash Carter, and a wonderful man and physicist named Wolfgang Panofsky was the chair.

We had a series of meetings with a counterpart group from the Soviet Academy of Sciences to talk about arms control and risk reduction matters, always with a high degree of scientific and technical content because that was the academy’s unique

niche.

In those days there were no other Track 2’s going on, so it was really unique and people in the US government were very interested in hearing about our discussions because there were very few channels of communication. On the Soviet side were scientists including Evgeny Velikhov and Roald Sagdeev who became close advisors to President Gorbachev.

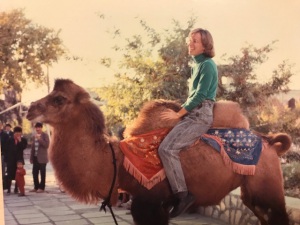

We also had a similar activity with the Chinese, although it wasn’t quite as mature as the discussion with the Soviets. That was very early in my career, and I like to say that I was a fly on a really interesting wall. It was a formative experience for me to be exposed to the caliber of people that were on our NAS committee and their thinking, and I’d say that experience was very influential in terms of my professional and personal development.

Where did that lead you?

After I’d been there for seven years or so – by then this was the first Bush administration (George H.W. Bush) and there were official arms control negotiations going on – I decided that I wanted to get some experience inside government. So I went into the U.S. Arms Control and Disarmament Agency and worked on the START negotiations. That was the first START Treaty.

It was a negotiation that went on for something like nine years, but I was lucky to be there when we got it over the finish line in 1991. And I have to say the round-the-clock negotiating sessions at the end went to like 3:00 in the morning on many nights with the Soviets in Geneva, and it was quite exciting to be there for the endgame. It was a huge accomplishment, and a really significant treaty.

And from there?

From there, I was at the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency and then the State Department until 2003, working mainly on strategic nuclear arms control. During that time, I was given the opportunity to go to the National War College for a year. And I have to say that was a really great experience and very broadening. The college is primarily for military officers, many of them headed for flag level, so it was a privilege to interact with that community and learn from each other. Little did I know then that I would end up working on the Senate Armed Services Committee and everything I was exposed to that year and the relationships I formed would come in pretty handy.

What did you do for the committee?

I worked on a broad range of foreign and defense policy issues, as well as arms control and nonproliferation issues. I had oversight for the Cooperative Threat Reduction budget at the Department of Defense and also the nuclear nonproliferation budget at the Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration.

And in that job I had the opportunity to do a lot of traveling throughout the former Soviet Union looking at sites where the Nunn-Lugar program (to secure and eliminate nuclear and other dangerous materials) was in effect.

And after President Obama was inaugurated, you joined the administration.

Yes, (former Undersecretary of State for Arms Control and International Security Affairs) Rose Gottemoeller brought me back into State to work on what became the New START Treaty. I chaired the interagency backstopping committee in Washington that provided guidance for the negotiators in Geneva and subsequently supported the ratification effort.

From there, I went to the National Security Council staff where I became the senior director for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation. I was there from the summer of 2011 to the end of 2014. I advised the President and National Security Advisor, and coordinated the work of the interagency in my area of responsibility. This included overseeing implementation of the New START Treaty, the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty including addressing concerns about Russia’s compliance, the Open Skies Treaty, the Biological Weapons Convention and the Chemical Weapons Convention. We also supported the negotiation of the Arms Trade Treaty and development of U.S. Conventional Arms Transfer Policy.

One of the core issues I focused on was strategic stability with Russia and the future of strategic arms control, and we developed and tried to advance some proposals on further nuclear reductions and on missile defense cooperation. I supported and participated in the trip of National Security Advisor Tom Donilon to Russia to meet with President Putin and discuss these proposals. It’s unfortunate that we were unable to make progress then, and the relationship deteriorated further after Russia invaded Ukraine. I hope that our countries can get back on a path of improving strategic stability.

What’s been the most rewarding job you’ve held – you know, besides NTI?

Well, I have to say there’s nothing like working for the President of the United States and the national security adviser in the White House. It’s an incredible honor, and it’s a huge responsibility. And it’s a huge opportunity to advance policies that you think are in the interest of our country, and to make sure that a policy process is in place that serves the president well.

Having said that – because the NSC really is an experience like none other – I have to say I loved my six years working for the Senate Armed Services Committee. That was a really valuable experience, and I learned a lot.

Similarly, the National Academy of Sciences was unique, and so ultimately I think the cumulative experience is valuable and everything I’ve done I think has allowed me to be more effective in the next job I’ve gone to.

So having worked across branches and agencies over many years in Washington, do you feel optimistic about our government’s ability to make progress and head in the right direction on the issues we care about at NTI? Of course, it is kind of an unusual time politically here right now.

Well, this is hardly an original observation, but it’s discouraging to see how Congress has become increasingly more partisan and less functional over time. There really did used to be more of a bipartisan consensus on foreign policy. Of course there were outliers, but there also was more commonality of view, a lot of effort to work together to forge sensible ways forward, bipartisan support for treaties that are in our nation’s interest. And I think we’re in a different place now, so it’s discouraging.

I am deeply concerned about the deterioration in US-Russian relations, about the North Korean nuclear threat, the risk of miscalculation, the dangers introduced by cyber threats. I don’t understand the logic of those who would walk away from the nuclear deal with Iran when Iran is complying with it. I have concerns about how our country is addressing these matters. Diplomacy is undervalued these days.

But I will end on a more optimistic note. We talked earlier about the fact that current events are reminding the American people and Congress of the realities and risks of living in a world with nuclear weapons. No one wants nuclear weapons to be used again. And the renewed attention to the possibility that this could actually happen in our lifetime should galvanize the public, the Congress, our leaders, and the international community to reinvigorate their efforts to reduce that risk. That is my hope, and that’s the goal we at NTI work toward every day.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest on nuclear and biological threats.

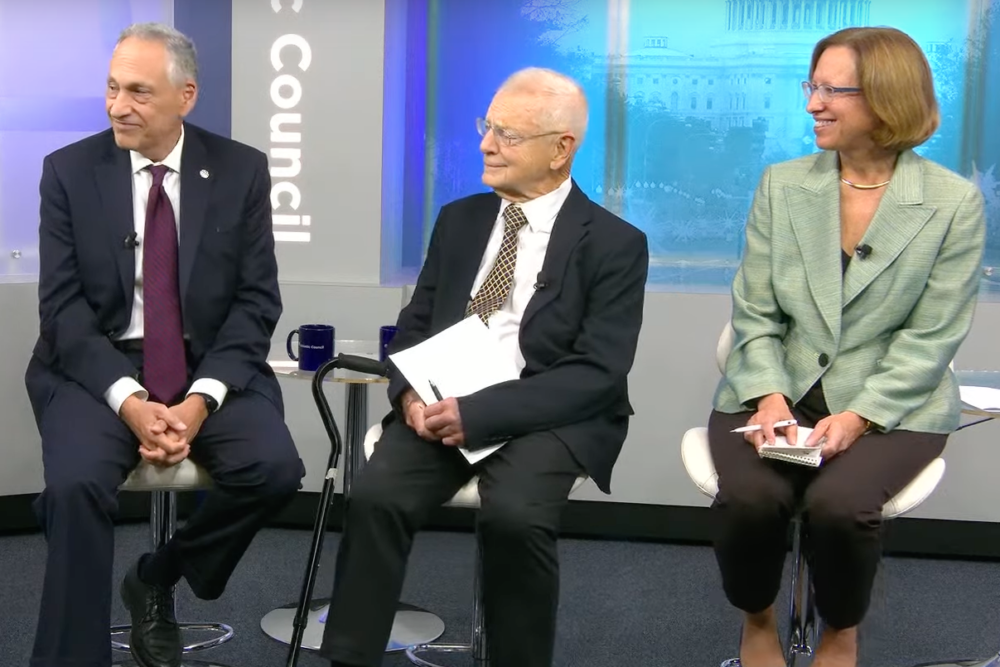

Lynn Rusten, vice president of NTI’s Global Nuclear Policy Program, shares her reaction to the 2023 Strategic Posture Report during a panel event at the Atlantic Council.

There is no noise at first, only a flash so bright that the soldiers see their own bones and blood vessels through their skin, as if they have x-ray vision.