Mimi Hall

Vice President, Communications

Atomic Pulse

In January 2001, just as NTI was opening its doors, Steve Andreasen was closing out on eight years as the director of defense policy and arms control on the National Security Council staff. Prior to his work at the White House during the eight years of the Clinton administration, he had served in the State Department in both the George H.W. Bush and Ronald Reagan administrations, dealing with a wide range of defense policy, arms control, nuclear weapons, and intelligence issues in the Bureaus of Intelligence and Research and Politico-Military Affairs and the office of Paul Nitze. He was also detailed to work on the staff of Senator Al Gore. When Andreasen’s tenure at the White House wrapped up, he returned to his home state of Minnesota and ran for Congress in Minnesota’s first Congressional District. He also began his association with NTI as a national security consultant, working to support NTI’s global nuclear security work across multiple programs and projects.

Over the course of this year, as NTI marks its 20th anniversary, our experts will share some reflections on two decades of working to build a safer world—accomplishments and challenges, lessons learned along the way, visions for the future. Today, we hear from Andreasen, who also teaches courses on national security policy and crisis management in foreign affairs at the University of Minnesota’s Hubert H. Humphrey School of Public Affairs.

You worked for Democratic and Republican administrations before you began working with NTI, and you’ve worked closely with senior leaders from both political parties in the United States. How important to you was it that NTI opened as a non-partisan organization?

NTI practiced non-partisanship from the start. NTI’s Board, leaders, and staff understand that to build durable solutions on national security issues, you need to build support from both sides of the aisle. That makes NTI a unique and attractive ship to be on. It helps explain why NTI is effective in its work and why NTI’s core staff have remained with the organization for so long, and why NTI continues to attract outstanding new talent.

In today’s political climate, do you think it’s possible to forge bipartisan support for reducing nuclear threats?

To extend the ship metaphor a bit further, the partisan waters in Washington today are rougher, deeper, and fouler than they were when NTI first set sail. Objectively, it’s harder today than at any time in NTI’s history to forge bipartisan support for anything, including reducing nuclear threats. But I don’t think the right question is, “is it possible,” but rather, “what can we do to make it possible?”

The “Shultz-Perry-Kissinger-Nunn” op-ed series in The Wall Street Journal fundamentally reframed the global debate around nuclear weapons and opened space for rethinking deterrence policy. You were one of the behind-the-scenes players who really drove that process. How did it all come about?

It began with Max Kampelman—a legendary lawyer, diplomat, and educator who worked on Hubert Humphrey’s first campaign for Mayor of Minneapolis and went on to work as a senior diplomat in both the Carter and Reagan administrations. Max wrote me a letter after reading an article I had written about President Reagan’s proposal to eliminate all ballistic missiles, and invited me to lunch in Washington to discuss it. Somewhat to my surprise, Max said, “Reagan also wanted to eliminate all nuclear weapons—let’s get back to work on that.” Max and I reached out to Reagan’s Secretary of State and our former boss, George Shultz—and physicist Sidney Drell who was working with Shultz at Stanford and who Max and I had both worked with. Shultz and Drell then took the initiative to hold a conference at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University in October 2006—twenty years after the historic Reykjavik summit—working closely with Sam Nunn at NTI, former Secretary of Defense and NTI Board Member Bill Perry, and Henry Kissinger. It took off from there.

The “Shultz-Perry-Kissinger-Nunn” op-eds call for reasserting the vision of a world free of nuclear weapons and practical measures toward achieving that goal. Many of the practical steps to get there have driven NTI’s work from the start. Where do you see the most progress towards the vision?

Since the first op-ed in January 2007, there has been progress—but it has been nothing close to a straight line. In June 2007, the UK government was the first to explicitly embrace the “vision and steps” framework put forward by the four U.S. statesmen. Many other former statesmen and governments followed. In the 2008 U.S. presidential campaign, both the Democratic and Republican nominees did the same. President Obama incorporated the vision and steps into his first foreign policy address as President in Prague in April 2009, and later that year chaired a UN Security Council meeting where at the head of state level, the full Security Council embraced the goal of a world without nuclear weapons and practical steps to move toward it. Shultz, Perry, Kissinger and Nunn all attended the session.

Perhaps not surprisingly, progress on practical steps has not come as easily as reaffirming the vision. But there has been progress, in particular on securing nuclear materials and limiting and reducing US and Russian strategic nuclear arms in the New START Treaty, which was recently extended by Presidents Biden and Putin. The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action negotiated with Iran in 2015 was also a big step forward.

What about the greatest barriers?

The first op-ed emphasized the importance of intensive work with leaders of the countries in possession of nuclear weapons to turn the goal of a world without nuclear weapons into a “joint enterprise.” It also emphasized the importance of resolving regional confrontations and conflicts that give rise to new nuclear powers. In both cases, success requires sustained leadership from the top of governments—and that has been uneven at best, or in some cases, overwhelmed by events. Sometimes, we’ve simply shot ourselves in the foot—for example, the unilateral U.S. withdrawal from the Iran agreement.

You’ve also worked to cultivate dialogue and engagement across the Euro-Atlantic region, including the United States and Russia, through the Euro-Atlantic Security Leadership Group (EASLG), which brings together former and current officials and experts from the region to test ideas and develop proposals for improving security and reducing nuclear risks. Have you made any progress here?

The Euro-Atlantic region has always been and remains today a vital piece of geography for nuclear threat reduction. The unresolved conflict in Ukraine has disrupted relations between the U.S., Europe, and Russia, created a potential flashpoint for catastrophic miscalculation, and undercut security and stability. All of this undercuts cooperation that is necessary for reducing nuclear risks.

Against that backdrop, the work of the EASLG—which has been up and running since 2016, and includes around sixty participants from more than 15 countries and the EU—is now recognized by governments across the Euro-Atlantic as a unique contributor, providing both ideas and support for concrete steps. Most recently, at the June 2021 Biden-Putin summit, the two presidents stated their support for the principle that “a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought”—a step that the EASLG has consistently and persistently called for since 2017.

NTI has played a central role in the EASLG, working with our partner organizations in this initiative (the European Leadership Network, Munich Security Conference, and Russian International Affairs Council) on the tough issues relating to Euro-Atlantic security, including Ukraine. The EASLG exemplifies what NTI does well in so many areas: patient and persistent support for progress. These investments can take time to pan out, and NTI gives them that time.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest on nuclear and biological threats.

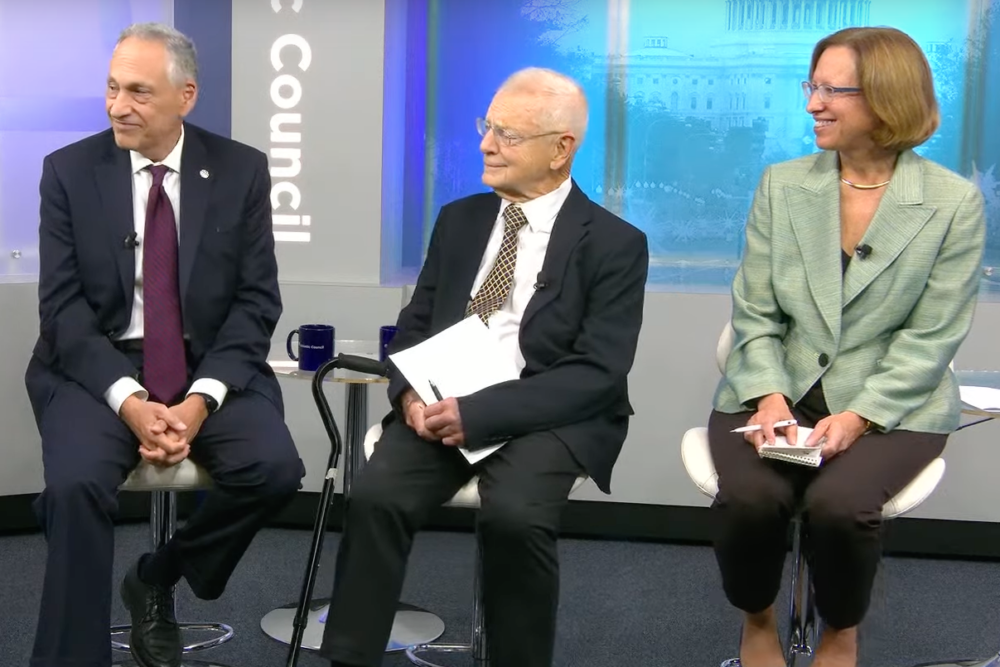

Lynn Rusten, vice president of NTI’s Global Nuclear Policy Program, shares her reaction to the 2023 Strategic Posture Report during a panel event at the Atlantic Council.

There is no noise at first, only a flash so bright that the soldiers see their own bones and blood vessels through their skin, as if they have x-ray vision.