The CNS North Korea Missile Test Database

A collection of missile tests including the date, time, missile name, launch agency, facility name, and test outcome.

Belarus has no weapons of mass destruction (WMD). Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the country transferred all of its Soviet-era nuclear warheads to Russia in the 1990s. It does not possess biological or chemical warfare programs. Though Belarus inherited no major ballistic missile production or design facilities from the Soviet Union, a number of firms continue to cooperate with Russian missile and space enterprises.

When Belarus gained independence in December 1991, there were 81 road-mobile SS-25s on its territory stationed at three missile bases, and an unknown number of tactical nuclear weapons. [1] During the 1980s, a number of units equipped with intermediate-range ballistic missiles (IRBMs) were also stationed in the Belarusian SSR; however, all of these weapons were eliminated under the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty by 1991. [2] Following Minsk's ratification of the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START) in February 1993 and accession to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) as a non-nuclear weapon state in July 1993, Belarus transferred all of its nuclear weapons to Russia, a process completed by November 1996. [3] No nuclear forces have been stationed in Belarus since that time, although the possibility of stationing Russian nuclear weapons in Belarus was broached by a number of Belarusian officials in the late 1990s. [4] Belarus has concluded an IAEA safeguards agreement, and has signed but not yet ratified the Additional Protocol (INFCIRC 495). Belarus participates in other voluntary agreements, including the Nuclear Suppliers Group and the International Convention for the Suppression of Acts of Nuclear Terrorism. Belarus did not participate in the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) negotiations nor has it signed or ratified the Treaty. [5]

Belarus has a small civilian nuclear research program under the aegis of the Belarusian National Academy of Sciences. In cooperation with the U.S. Department of Energy, there are ongoing efforts as part of the Global Threat Reduction Initiative (GTRI) to convert a booster subcritical assembly, housed at the Sosny facility near Minsk, from highly enriched uranium (HEU) to low enriched uranium (LEU) fuel. [6] The United States estimated that, at the time of Belarus' December 2010 commitment to return its HEU to Russia, Belarus possessed an estimated 230 kg of HEU. [7] The material was provided by the Soviet government for use in Sosny's IRT nuclear research reactor, which was shut down in 1989. [8] The U.S. government pledged to provide both financial and technical assistance to expedite the process of returning the HEU to Russia. [9] Although 85 kg of HEU was removed under the GTRI in November 2010, Belarus suspended cooperation in August 2011 after the United States imposed economic sanctions in response to the government's violent suppression of political opponents under President Lukashenko's regime. [10]

Belarus has one nuclear power plant currently under construction in Astravyets District near the Lithuanian border. The plant is being built by the Russian nuclear power firm Atomstroyexport with Russian financing. [11] Fuel loading of the first of two Astravyets reactors is expected to be finished by the end of 2020. [12] Construction of the second reactor is scheduled for completion in 2022 and will double the plant's capacity to 2.4 gigawatts. [13] Lithuania has environmental concerns about the nuclear power plant, and has attempted unsuccessfully to block its construction under international law. [14]

Belarus does not have a biological warfare (BW) program, and there is no indication that it has plans to establish such a program in the future. Although Belarus was a Soviet republic in 1972, it is a signatory of the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BTWC), which it ratified in 1975. [15]

In January 1992, Russian President Boris Yeltsin declared that all former Soviet chemical weapons had been transferred to Russia. Belarus does not have a chemical warfare (CW) program, and is a party to the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), which it ratified in 1996. [16]

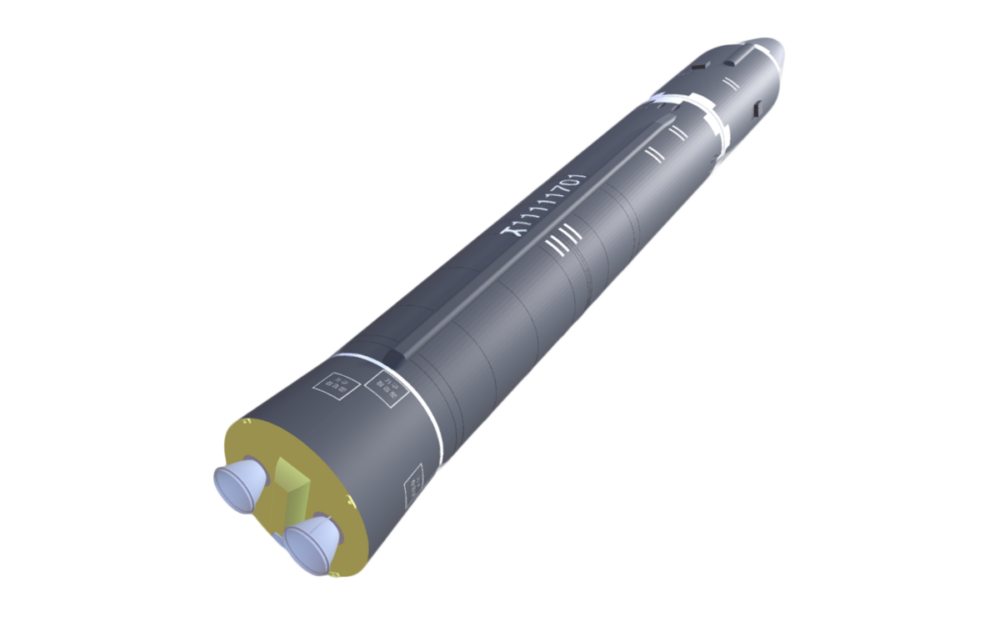

Belarus did not inherit any major missile production or design facilities from the Soviet Union. Dismantlement of the 81 SS-25 ICBM launch positions under the Cooperative Threat Reduction (CTR) program ceased in 1997 after a chill in U.S.-Belarusian relations, and over 1,000 tons of rocket fuel, as well as over 7,000 tonnes of oxidizer, have never been eliminated. [17] Moreover, a number of Belarusian firms cooperate with Russian missile/space enterprises, including the Minsk Wheeled Prime Mover Plant (MZKT), which produced transporter-erector launcher (TEL) vehicles for SS-25 and SS-27 road-mobile intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). [18] Some Belarusian enterprises also successfully market and export upgrades, repairs, and refurbishment of Soviet-designed short-range surface-to-air missile systems. [19]

Since 2016, Belarus and Russia have had in place a joint missile defense system. [20] Belarus employs Russian-built air defense systems, including the S-300 (NATO Designation: SA-10 'Grumble') and the Tor-M2 (SA-15 'Gauntlet') . [21] [22] In 2017, together with China, Belarus set up a production line for Polonez, a short-range multiple-launch missile system. The upgraded version – Polonez-M – was integrated into the Belarusian armed forces in 2019 and supplied to Azerbaijan. [23] Belarus is not a member of the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR), though it has been considered for membership in the past. [24]

Sources:

[1] Joseph Cirincione, Jon B. Wolfsthal, Miriam Rajkumar, Deadly Arsenals: Nuclear, Biological, and Chemical Threats, p. 365, Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment, 2005.

[2] Joseph Cirincione, Jon B. Wolfsthal, Miriam Rajkumar, Deadly Arsenals: Nuclear, Biological, and Chemical Threats, p. 367, Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment, 2005.

[3] Joseph Cirincione, Jon B. Wolfsthal, Miriam Rajkumar, Deadly Arsenals: Nuclear, Biological, and Chemical Threats, p. 367, Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment, 2005.

[4] Maria Katsva, “Russia Looks to Expand Nuclear Weapons Option,” Economists for Peace and Security, June 1999, epsusa.org.

[5] Belarus, Nuclear Weapons Ban Monitor, www.banmonitor.org.

[6] S. Sikorin, J. Thomas, et al., The Shipment of Russian-Origin Highly Enriched Uranium Spent and Fresh Nuclear Fuel from Belarus and Delivery of Fresh Low Enriched Uranium Nuclear Fuel to Belarus,” International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), Presented at the International Conference on Research Reactors: Safe Management and Effective Utilization, November 2011, iaea.org.

[7] William Potter, “Belarus Agrees to Remove All HEU,” CNS Feature Story, 1 December 2010, www.nonproliferation.org; Pavel Podvig, “Belarus will remove HEU by 2012,” International Panel on Fissile Materials, 1 December 2010, www.fissilematerials.org.

[8] “Joint Statement by Secretary of State Clinton and Foreign Minister Martynov,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Belarus, 1 December 2010, www.mfa.gov.by.

[9] Michael Schwirtz, “Belarus Suspends Pact to Give Up Enriched Uranium,” The New York Times, 20 August 2011, www.nytimes.com.

[10] Excerpt from report in English by Belarusian privately-owned news agency Belapan, “Russia plans to fund construction of Belarusian nuclear plant – official,” BBC Monitoring Kiev Unit, 9 October 2009, www.monitor.bbc.co.uk.

[11] “Nuclear Power in Belarus," World Nuclear Association, Updated February 2013, world-nuclear.org.

[12] “Belarus begins fueling its first nuclear power plant,” Al Jazeera, 7 August 2020, www.aljazeera.com.

[13] Ministry of Energy Republic of Belarus, www.minenergo.gov.by.

[14] Nuclear Power in Belarus, October 2020, www.world-nuclear.org.

[15] “States Parties to this Convention,” Organization for the Prohibition of Biological Weapons, June 2005, opbw.org.

[16] “Status of Participation in the CWC,” Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, 21 May 2009, opcw.org.

[17] Joseph Cirincione, Jon B. Wolfsthal, Miriam Rajkumar, Deadly Arsenals: Nuclear, Biological, and Chemical Threats, p. 367, Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment, 2005.

[18] “RT-2PM – SS-25 SICKLE,” Global Security.org.

[19] Melissa Hanham, “North Korea's Procurement Network Strikes Again: Examining How Chinese Missile Hardware Ended up in Pyongyang,” Nuclear Threat Initiative, 31 July 2012, nti.org; Proliferation: Threat and Response, “Russia, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, and Belarus,” United States Department of Defense, January 2001, hosted on fas.org.

[20] “Россия и Белоруссия завершили формирование объединенной системы ПВО,” Interfax, 6 April 2016, www.interfax.ru.

[21] “Belarus Receives Fourth Battalion Of S-300 PS Air Defense Systems,” 6 May 2016, www.defenseworld.net.

[22] “Belarus Received Early Battery Of Tor-M2 Missile Systems From Russia,” 28 November 2018, www.charter97.org.

[23] Katia Glod, “Slipping Out of the Russian Sphere?” 21 July 2020, www.cepa.org.

[24] “Missile Technology Control Regime Plenary Meeting,” U.S. Department of State, April 2011, state.gov.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest on nuclear and biological threats.

A collection of missile tests including the date, time, missile name, launch agency, facility name, and test outcome.

At this critical juncture for action on climate change and energy security, 20 NGOs from around the globe jointly call for the efficient and responsible expansion of nuclear energy and advance six key principles for doing so.

Information and analysis of nuclear weapons disarmament proposals and progress in Belarus