China Nuclear Overview

About the image

Background

This page is part of the China Country Profile.

On 16 October 1964 China exploded its first nuclear device. 1 China has since consistently asserted that its nuclear doctrine is based on the concept of no-first-use, and Chinese military leaders have characterized the country’s nuclear weapons as a minimum deterrent against nuclear attacks. 2 Although the exact size of China’s nuclear stockpile has not been publicly disclosed, reports indicate that as of 2011 China has produced a total of 200 to 300 nuclear warheads.3 In 2015, Robert S. Norris and Hans M. Kristensen estimated the size of China’s current nuclear stockpile to be approximately 260 warheads and slowly increasing. 4 Roughly 190 of these warheads are currently considered operational. 5

Since the inception of its nuclear weapons program, China has relied on a mixture of foreign and indigenous inputs to steadily develop and modernize its nuclear arsenal from its first implosion device to the development of tactical nuclear weapons in the 1980s. 6 As a result, The Federation of American Scientists assesses China to have at least six different types of nuclear payload assemblies: a 15-40 kiloton (kt) fission bomb; a 20 kt missile warhead; a 3 megaton (mt) thermonuclear missile warhead; a 3 mt thermonuclear gravity bomb; a 4-5 mt missile warhead; and a 200-300 kt missile warhead. China is thought to possess a total of some 150 tactical nuclear warheads on its short-range ballistic, and possibly cruise missiles. 7

In its most recent (2015) Annual Report to Congress on the Military and Security Developments of the People’s Republic of China, the U.S. Department of Defense stated that China’s nuclear-capable missile arsenal consists of a total of 50-60 intercontinental ballistic mssiles (ICBMs), including: silo-based, liquid-fueled DF-5 (CSS-4) ICBMs; solid-fueled, road-mobile DF-31 (CSS 10 Mod-1) and DF-31A (CSS-10 Mod 2) ICBMs; limited-range DF-4 (CSS-3) ICBMs; and liquid-fueled DF-3 (CSS-2) intermediate-range ballistic missiles; and DF- 21 (CSS-5) road-mobile, solid-fueled MRBMs. Four JIN-class SSBNs have been delivered to the People Liberation Army Navy (PLAN), which will eventually carry JL-2 submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs). 8 China also possesses the DF-16 (CSS-11), the DF-15 (CSS-6), and 700-750 DF-11 (CSS-7) short-range ballistic missiles (SRBMs). China, however; maintains significantly fewer launchers, and 200-500 DH-10s (a cruise missile thought to be able to support a nuclear payload). The Department of Defense assesses that all Chinese SRBMs are deployed near Taiwan. Most recently, China has deployed its first MIRV-equipped missile, the DF-5 (CSS-4 Mod 3), and the DF-21D (CSS-5 Mod 5) anti-ship ballistic missile. It is currently developing the road-mobile DF-41 (CSS-X-20) ICBM. 9

There is an ongoing effort to shift from liquid-fueled missiles to solid-fueled missiles. 10 China has also continued to develop new missile launch sites and underground storage facilities in remote inland regions, including the Gobi Desert and the Tibetan highlands. As there is no evidence of long-range missiles being deployed to these new locations, the launch sites appear to be intended primarily as forward bases for potential launches against Russia and India. 11

Even as it continues to develop its arsenal, however, China has also slowly moved towards increased openness in its willingness to share a limited amount of deployment information and strategy. For example, the 2010 China Defense White Paper details Beijing’s no-first-use policy and roughly outlines several stages of nuclear alert. The paper states that “nuclear-weapon states should negotiate and conclude a treaty on no-first-use of nuclear weapons against each other.” The White Paper also states China’s “unequivocal commitment that under no circumstances will it use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear-weapon states or nuclear-weapon-free zones.” 12 China’s 2013 Defense White Paper did not specifically use the words “no first use.” 13 However, the director of the Chinese Academy of Military Science subsequently reiterated that there is “no sign that China is going to change a policy it has wisely adopted and persistently upheld for half a century,” and China reaffirmed its no-first-use policy in its most recent Defense White Paper publication. 14

History

China’s efforts to develop a nuclear weapons program began in response to what it deemed as “nuclear blackmail” from the United States. 15 In July 1950, at the very beginning of the Korean War, U.S. President Harry Truman ordered ten nuclear-configured B-29s to the Pacific, with the intention of deterring China from entering the Korean War. 16 In 1952, U.S. President-elect Dwight Eisenhower publicly hinted that he would authorize the use of nuclear weapons against China if the Korean War armistice talks continued to stagnate. 17 In 1954, the commander of the U.S. Strategic Air Command, General Curtis LeMay, voiced his support for the use of nuclear weapons if China resumed fighting in Korea. LeMay stated, “There are no suitable strategic air targets in Korea. However, I would drop a few bombs in proper places like China, Manchuria and Southeastern Russia. In those ‘poker games,’ such as Korea and Indo-China, we… have never raised the ante-we have always just called the bet. We ought to try raising sometime.” 18 Not long after, in January 1955, U.S. Navy Admiral Arthur Radford also publicly advocated the use of nuclear weapons if China invaded South Korea. 19

China began developing nuclear weapons in the winter of 1954. The Third Ministry of Machinery Building (renamed the Second Ministry of Machinery Building in 1957, the Ministry of Nuclear Industry in 1982, and replaced by Department of Energy and China National Nuclear Corporation in 1988) was established in 1956. 20 With some Soviet assistance, nuclear research began at the Institute of Physics and Atomic Energy in Beijing, and a gaseous diffusion uranium enrichment plant in Lanzhou was constructed to produce weapons-grade uranium. 21 On 15 October 1957, the USSR and China signed an agreement on new defense technology, in which Moscow agreed to supply a “sample of an atomic bomb” and technical data from which Beijing could manufacture a nuclear weapon. 22 From 1955 to 1959, approximately 260 Chinese nuclear scientists and engineers went to the Soviet Union, while roughly the same number of Soviet nuclear experts traveled to China to work in its nuclear industry. However, by 1959 the rift between the Soviet Union and China had become so great that the Soviet Union discontinued all assistance to China. 23

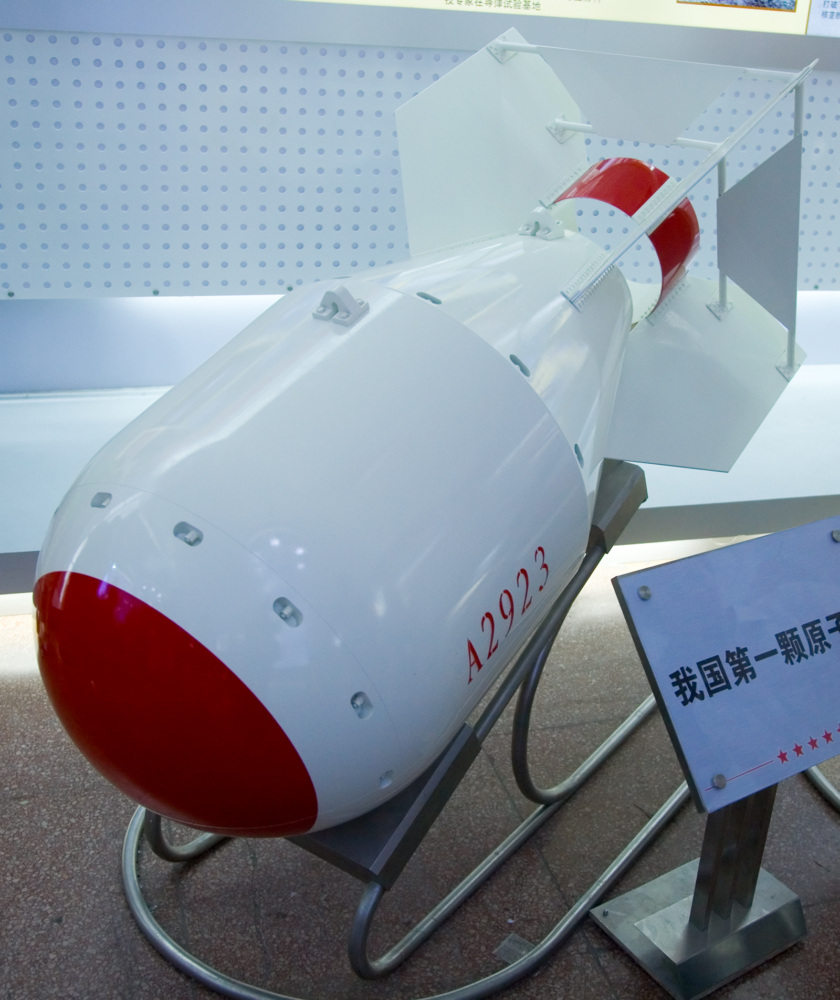

China successfully tested its first atomic bomb on 16 October 1964 — with highly enriched uranium produced at the Lanzhou facility — and just 32 months later on 17 June 1967, China tested its first thermonuclear device. 24 This achievement is remarkable in that the time span between the two events is substantially shorter than it was for the other nuclear weapon states. In comparison, 86 months passed between the United States’ first atomic test and its first hydrogen bomb test; for the USSR, it was 75 months; for the UK, 66 months; and for France, 105 months. 25

On 27 October 1966, China launched a Dong Feng-2 (DF-2) medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM) from the Shuangchengzi Missile Test Site in Gansu province, which struck its target in the Lop Nur Test Site. The missile carried a 12 kiloton nuclear warhead, marking the only time that a country has tested a nuclear warhead on a ballistic missile over populated areas. 26

Starting in the mid-1960s, China adopted a policy known as the “Third Line Construction” (三线建设), which was an effort to construct redundant facilities for strategic interests such as the steel, aerospace, and nuclear industries in the interior of China to make them less vulnerable to attack. 27 “Third Line Construction” nuclear facilities included a gaseous diffusion uranium enrichment facility at Heping, a plutonium production reactor and extraction facility at Guangyuan, the Nuclear Fuel Component Plant at Yibin, and a nuclear weapon design facility at Mianyang. The “Third Line” was conducted during China’s Third (1966-70) and Fourth (1971-1975) Five-Year Economic Plans. 28

Nuclear Modernization During the 1980s and Beyond

China’s nuclear tests in the late-1980s and 1990s were geared toward further modernizing its nuclear forces. Although China officially declared in 1994 that these tests were for improving safety features on existing warheads, they were also likely intended for the development of new, smaller warheads for China’s next-generation solid-fueled ICBMs (e.g., DF-31 and DF-31A), and possibly to develop a multiple warhead (MRV or MIRV) capability as well. 29 China’s last test was on 29 July 1996, and less than two months later on 24 September 1996 Beijing signed the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT). 30 In order to sign the treaty China overcame several of its initial concerns, including allowing an exemption for Peaceful Nuclear Explosions and the use of national technical means and on-site inspections for verification. The National People’s Congress, however, has yet to ratify the treaty.

China’s 1996 signing of the CTBT was the latest in a series of policy shifts on nuclear nonproliferation issues. In fact, it was during the 1980s that China’s position on nuclear proliferation first started to change. Since the 1960s, Beijing had criticized the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) as imbalanced and discriminatory, but by the 1980s the country had also indicated that it accepted in principle the norm of nuclear nonproliferation. 31 In 1984, China joined the IAEA and agreed to place all of its exports under international safeguards; that same year, during a trip to the United States, Chinese Premier Zhao Ziyang provided Washington with verbal assurances that China did not advocate or encourage nuclear proliferation. 32 In 1990, though still not a member of the NPT, China attended the fourth NPT review conference and, while it criticized the treaty for not banning the deployment of nuclear weapons outside national territories and for not including concrete provisions for general nuclear disarmament, it also stated that the treaty had a positive impact and contributed to the maintenance of world peace and stability. 33 In August 1991, shortly after France acceded to the NPT, China also declared its intention to join, though it again expressed its reservations about the treaty’s discriminatory nature. 34

China formally acceded to the NPT in March 1992, as a nuclear weapon state. In its statement of accession, the Chinese government called on all nuclear weapon states to issue unconditional no-first-use pledges, to provide negative and positive security assurances to non-nuclear weapon states, to support the development of nuclear weapon-free zones, to withdraw all nuclear weapons deployed outside of their national territories, and to halt the arms race in outer space. 35 Since its accession, China has praised the NPT’s role in preventing the proliferation of nuclear weapons, and also supported the decision to indefinitely extend the NPT at the 1995 Review and Extension Conference. 36

However, China has continued to state that it views nonproliferation not as an end in itself, but rather as a means to the ultimate objective of the complete prohibition and thorough destruction of nuclear weapons. 37 Despite this, China was embroiled in nuclear proliferation scandals throughout the late 1980’s and early 1990’s, particularly with respect to its sale of ring magnets to Pakistan in 1995. 38 China provided Pakistan with a nuclear bomb design (used in China’s October 1966 nuclear test). These designs were later passed to Libya by the A.Q. Khan network, and discovered by IAEA inspectors in 2004 after then President Muammar Qadhafi renounced his nuclear weapons program and allowed inspectors to examine related facilities. The plans contained portions of Chinese text with explicit instructions for the manufacture of an implosion device. 39

The Future of China's Nuclear Modernization

There is much speculation that China’s nuclear modernization program may be geared toward developing the capacity to move from a strategy of minimum deterrence to one of limited deterrence. Under a “limited deterrence” doctrine, China would need to target nuclear forces in addition to cities, which would require expanded deployments. However, such a limited deterrence capability may still be a long way off. According to Alastair Johnston, “It is fairly safe to say that Chinese capabilities come nowhere near the level required by the concept of limited deterrence.” 40

China is working to expand its nuclear deterrent by developing an SSBN force. 41 According to the Department of Defense’s 2013 Annual Report to Congress on the Military and Security Developments of the People’s Republic of China, these developments will give the PLA Navy its “first credible sea-based nuclear deterrent.” 42

Meanwhile, tensions between China and Taiwan have declined, and in the wake of Japan‘s 2011 nuclear crisis, China and Taiwan are taking concrete measures to cooperate on nuclear safety issues. Such cross-strait cooperation includes establishing a formal nuclear safety agreement and an official contact mechanism between the two sides, which will be used to facilitate information exchanges and emergency responses in case of an accident. 43 While China’s decreased threat perception may not slow its nuclear modernization efforts, which are seen simply as representing the replacement of obsolete equipment, it does have the potential to slow acquisitions in key areas — for example, the buildup of short-range missiles. If sustained, the shift may also make both sides more amenable to nonproliferation efforts such as ratification of the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty.

Stay Informed

Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest on nuclear and biological threats.

Glossary

- Nuclear (use) doctrine

- Nuclear (use) doctrine: The fundamental principles by which a country’s political or military leaders guide their decision-making regarding the conditions for the use of nuclear weapons.

- First-use

- The introduction of nuclear weapons, or other weapons of mass destruction, into a conflict. In agreeing to a "no-first-use" policy, a country states that it will not use nuclear weapons first, but only under retaliatory circumstances. See entry for No-First-Use

- Tactical nuclear weapons

- Short-range nuclear weapons, such as artillery shells, bombs, and short-range missiles, deployed for use in battlefield operations.

- Kiloton

- Kiloton: A term used to quantify the energy of a nuclear explosion that is equivalent to the explosion of 1,000 tons of trinitrotoluene (TNT) conventional explosive.

- Fission bomb

- Fission bomb: A nuclear bomb based on the concept of releasing energy through the fission (splitting) of heavy isotopes, such as Uranium-235 or Plutonium-239.

- Megaton (MT)

- Megaton (MT): The energy equivalent released by 1,000 kilotons (1,000,000 tons) of trinitrotoluene (TNT) explosive. Typically used as the unit of measurement to express the amount of energy released by a nuclear bomb.

- Thermonuclear weapon

- Thermonuclear weapon: A nuclear weapon in which the fusion of light nuclei, such as deuterium and tritium, leads to a significantly higher explosive yield than in a regular fission weapon. Thermonuclear weapons are sometimes referred to as staged weapons, because the initial fission reaction (the first stage) creates the condition under which the thermonuclear reaction can occur (the second stage). Also archaically referred to as a hydrogen bomb.

- Cruise missile

- An unmanned self-propelled guided vehicle that sustains flight through aerodynamic lift for most of its flight path. There are subsonic and supersonic cruise missiles currently deployed in conventional and nuclear arsenals, while conventional hypersonic cruise missiles are currently in development. These can be launched from the air, submarines, or the ground. Although they carry smaller payloads, travel at slower speeds, and cover lesser ranges than ballistic missiles, cruise missiles can be programmed to travel along customized flight paths and to evade missile defense systems.

- Intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM)

- Intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM): A ballistic missile with a range greater than 5,500 km. See entry for ballistic missile.

- Submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM)

- SLBM: A ballistic missile that is carried on and launched from a submarine.

- No-First-Use

- No-First-Use: A pledge on the part of a nuclear weapon state not to be the first party to use nuclear weapons in a conflict or crisis. No-first-use guarantees may be made in unilateral statements, bilateral or multilateral agreements, or as part of a treaty creating a nuclear-weapon-free zone.

- Uranium

- Uranium is a metal with the atomic number 92. See entries for enriched uranium, low enriched uranium, and highly enriched uranium.

- Nuclear weapon

- Nuclear weapon: A device that releases nuclear energy in an explosive manner as the result of nuclear chain reactions involving fission, or fission and fusion, of atomic nuclei. Such weapons are also sometimes referred to as atomic bombs (a fission-based weapon); or boosted fission weapons (a fission-based weapon deriving a slightly higher yield from a small fusion reaction); or hydrogen bombs/thermonuclear weapons (a weapon deriving a significant portion of its energy from fusion reactions).

- Highly enriched uranium (HEU)

- Highly enriched uranium (HEU): Refers to uranium with a concentration of more than 20% of the isotope U-235. Achieved via the process of enrichment. See entry for enriched uranium.

- Thermonuclear weapon

- Thermonuclear weapon: A nuclear weapon in which the fusion of light nuclei, such as deuterium and tritium, leads to a significantly higher explosive yield than in a regular fission weapon. Thermonuclear weapons are sometimes referred to as staged weapons, because the initial fission reaction (the first stage) creates the condition under which the thermonuclear reaction can occur (the second stage). Also archaically referred to as a hydrogen bomb.

- Hydrogen bomb

- Hydrogen bomb: See entries for Nuclear weapon and Thermonuclear weapon.

- Multiple Independently-targetable Reentry Vehicle (MIRV)

- An offensive ballistic missile system with multiple warheads, each of which can strike a separate target and can be launched by a single booster rocket.

- Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT)

- The CTBT: Opened for signature in 1996 at the UN General Assembly, the CTBT prohibits all nuclear testing if it enters into force. The treaty establishes the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO) to ensure the implementation of its provisions and verify compliance through a global monitoring system upon entry into force. Pending the treaty’s entry into force, the Preparatory Commission of the CTBTO is charged with establishing the International Monitoring System (IMS) and promoting treaty ratifications. CTBT entry into force is contingent on ratification by 44 Annex II states. For additional information, see the CTBT.

- Peaceful Nuclear Explosion (PNE)

- PNEs are nuclear explosions carried out for non-military purposes, such as the construction of harbors or canals. PNEs are technically indistinguishable from nuclear explosions of a military nature. Although Article V of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) allows for PNEs, no significant peaceful benefits of these explosions (that outweigh the drawbacks), have been discovered. In the Final Document of the 2000 NPT Review Conference, the state parties agreed that Article V of the NPT is to be interpreted in light of the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, which will ban all nuclear explosions, including PNEs, once it enters into force.

- National technical means (NTM)

- NTM: Satellites, aircraft, electronic, and seismic monitoring devices used to monitor the activities of other states, including treaty compliance and movement of troops and equipment. Some agreements include measures that explicitly prohibit tampering with other parties' NTM. See entries for Transparency measures and Verification.

- Nonproliferation

- Nonproliferation: Measures to prevent the spread of biological, chemical, and/or nuclear weapons and their delivery systems. See entry for Proliferation.

- Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT)

- The NPT: Signed in 1968, the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) is the most widely adhered-to international security agreement. The “three pillars” of the NPT are nuclear disarmament, nonproliferation, and peaceful uses of nuclear energy. Article VI of the NPT commits states possessing nuclear weapons to negotiate in good faith toward halting the arms race and the complete elimination of nuclear weapons. The Treaty stipulates that non-nuclear-weapon states will not seek to acquire nuclear weapons, and will accept International Atomic Energy Agency safeguards on their nuclear activities, while nuclear weapon states commit not to transfer nuclear weapons to other states. All states have a right to the peaceful use of nuclear energy, and should assist one another in its development. The NPT provides for conferences of member states to review treaty implementation at five-year intervals. Initially of a 25-year duration, the NPT was extended indefinitely in 1995. For additional information, see the NPT.

- International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA)

- IAEA: Founded in 1957 and based in Vienna, Austria, the IAEA is an autonomous international organization in the United Nations system. The Agency’s mandate is the promotion of peaceful uses of nuclear energy, technical assistance in this area, and verification that nuclear materials and technology stay in peaceful use. Article III of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) requires non-nuclear weapon states party to the NPT to accept safeguards administered by the IAEA. The IAEA consists of three principal organs: the General Conference (of member states); the Board of Governors; and the Secretariat. For additional information, see the IAEA.

- Safeguards

- Safeguards: A system of accounting, containment, surveillance, and inspections aimed at verifying that states are in compliance with their treaty obligations concerning the supply, manufacture, and use of civil nuclear materials. The term frequently refers to the safeguards systems maintained by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) in all nuclear facilities in non-nuclear weapon state parties to the NPT. IAEA safeguards aim to detect the diversion of a significant quantity of nuclear material in a timely manner. However, the term can also refer to, for example, a bilateral agreement between a supplier state and an importer state on the use of a certain nuclear technology.

See entries for Full-scope safeguards, information-driven safeguards, Information Circular 66, and Information Circular 153. - Positive security assurances

- Positive security assurances: A guarantee given by a nuclear weapon state to a non-nuclear weapon state for assistance if the latter is targeted or threatened with nuclear weapons. See entry for Negative security assurances.

- Non-nuclear weapon state (NNWS)

- Non-nuclear weapon state (NNWS): Under the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), NNWS are states that had not detonated a nuclear device prior to 1 January 1967, and who agree in joining the NPT to refrain from pursuing nuclear weapons (that is, all state parties to the NPT other than the United States, the Soviet Union/Russia, the United Kingdom, France, and China).

- Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone (NWFZ)

- NWFZ: A geographical area in which nuclear weapons may not legally be built, possessed, transferred, deployed, or tested.

Sources

- "中华人民共和国政府声明 [Declaration of the Government of the People's Republic of China]," Renmin Ribao, 16 October 1964, via: http://news.xinhuanet.com.

- Specifically, "中国政府郑重宣布,中国在任何时候、任何情况下,都不会首先使用核武器." in "中华人民共和国政府声明 [Declaration of the Government of the People's Republic of China]," Renmin Ribao, 16 October 1964, via: http://news.xinhuanet.com; Wang Hui and Hui Chengzhuo, "中国始终恪守不首先使用核武器政策 [China Consistently Upholds the Policy of No First Use of Nuclear Weapons]," Xinhua, 31 March 2011, http://news.xinhuanet.com; Nie Rongzhen, 聂荣臻回忆录 [Nie Rongzhen Memoirs] vol. 2 (Beijing: People Liberation Army Press, 1984), p. 810.

- Gregory Kulacki, “China’s Nuclear Arsenal: Status and Evolution,” Union of Concerned Scientists, October 2011, www.ucsusa.org.

- Hans M. Kristensen and Robert S. Norris, “Chinese Nuclear Forces 2015,” Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, 1 July 2015, www.thebulletin.org.

- "Military Spending and Armaments, Nuclear Forces: China," Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, 2014, www.sipri.org.

- Robert S. Norris and Hans M. Kristensen, “Chinese Nuclear Forces, 2011,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, vol. 67, no. 6, 1 November 2011, pp. 81-85.

- "Nuclear Weapons - China Nuclear Forces," Federation of American Scientists, www.fas.org.[8] U.S. Department of Defense, “Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China,” April 2015, www.defense.gov.

- U.S. Department of Defense, “Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China,” April 2015, www.defense.gov.

- U.S. Department of Defense, “Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China,” April 2015, www.defense.gov.

- Hans Kristensen, "Extensive Nuclear Missile Deployment Area Discovered in Central China," Federation of American Scientists, 15 May 2008, www.fas.org.

- Hans Kristensen, “Extensive Nuclear Missile Deployment Area Discovered in Central China,” Federation of American Scientists, 15 May 2008, www.fas.org.

- Hans Kristensen, “Extensive Nuclear Missile Deployment Area Discovered in Central China,” Federation of American Scientists, 15 May 2008, www.fas.org.

- Information Office of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China, “China’s National Defense in 2010,” March 2011, via: www.news.xinhuanet.com.

- Information Office of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China, “The Diversified Employment of China’s Armed Forces,” April 2013, www.china.org.cn.

- Yao Yunzhu, “China Will Not Change Its Nuclear Policy,” China US Focus, 22 April 2013, www.chinausfocus.com; Ministry of National Defense of the People’s Republic of China, “China’s Military Strategy,” May 2015, www.eng.mod.gov.cn.

- “中华人民共和国政府声明 [Declaration of the Government of the People’s Republic of China],” Renmin Ribao, 16 October 1964, via: http://news.xinhuanet.com.

- Roger Dingman, “Atomic Diplomacy during the Korean War,” International Security, vol. 13, no. 3, Winter 1988-1989, pp. 50-91.

- John Wilson Lewis and Xue Litai, China Builds the Bomb (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1988), pp. 13-14.

- David Alan Rosenberg and W. B. Moore, “‘A Smoking Radiating Ruin at the End of Two Hours:’ Documents on American Plans for Nuclear War with the Soviet Union, 1954-1955,” International Security vol. 6, no. 3, Winter, 1981-1982, pp. 3-38.

- John Wilson Lewis and Xue Litai, China Builds the Bomb, (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1988), p. 32.

- John Wilson Lewis and Xue Litai, China Builds the Bomb, (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1988), pp. 47-48; “1955-1998 年大事记 [1955-1998 Chronology],” China National Nuclear Corporation, 30 December 2006, www.cnnc.com.cn.

- John Wilson Lewis and Xue Litai, China Builds the Bomb, (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1988), pp. 114-115; Robert S. Norris and Hans M. Kristensen, “Chinese Nuclear Forces, 2011,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, vol. 67, no. 6, 1 November 2011, pp. 81-87.

- The details of the agreement were not revealed until the Chinese government made a public statement in reply to the USSR on 15 August 1963 that “As far back as 20 June 1959…the Soviet Government unilaterally tore up the agreement on new technology for national defense concluded between China and the Soviet Union on 15 October 1957, and refused to provide China with a sample of an atomic bomb and technical data concerning its manufacture.” Peking Review, no. 33, 1963, as quoted in Hungdah Chiu, “Communist China’s Attitude Toward Nuclear Tests,” The China Quarterly, no. 21, January-March 1965, p. 96.

- John Wilson Lewis and Xue Litai, China Builds the Bomb (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1988), pp. 114-115.

- Charles H. Murphy, “Mainland China’s Evolving Nuclear Deterrent,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, January 1972, pp. 29-30.

- John Wilson Lewis and Xue Litai, China Builds the Bomb (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1988), pp. 202-203. See photos at: “组图:中国第一次导弹核武器试验获得成功 [Photos: China’s First Successful Nuclear Missile Test],” People’s Network Military Channel, ed. Yang Tiehu, Photo credit: China Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center, 16 September 2006, http://military.people.com.cn.

- Xia Fei, “三线建设:毛泽东的一个重大战略决策 [Third Line Construction: One of Mao’s Important Strategic Decisions],” News of the Communist Party of China, 2008, http://dangshi.people.com.cn.

- Robert S. Norris and Hans M. Kristensen, “Chinese Nuclear Forces, 2011,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, vol. 67, no. 6, 1 November 2011, pp. 81-85.

- Robert S. Norris and Hans M. Kristensen, “Chinese Nuclear Forces, 2011,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, vol. 67, no. 6, 1 November 2011, pp. 81-87.

- “中华人民共和国政府关于停止核试验的声明 [Government Statement on the Moratorium of Nuclear Tests],” Xinhua, 29 July 1996, via: www.cnr.cn.

- Mingquan Zhu, “The Evolution of China’s Nuclear Nonproliferation Policy,” The Nonproliferation Review, vol. 4, no. 2, Winter 1997, pp. 40-48.

- “China Joins Agency that Inspects Reactors,” New York Times, 12 October 1983, p. A5, http://web.lexis-nexis.com; David Willis, “Some Progress is Seen on Containing the Spread of Nuclear Weapons,” Christian Science Monitor, 25 October 1983, p. 1, via: http://web.lexis-nexis.com; “Chinese Premier’s Remarks at White House Banquet,” BBC Summery of World Broadcasts, 12 January 1984, http://web.lexis-nexis.com.

- “必须全面禁止和彻底销毁核武器 [Must Completely Prohibit and Dismantle Nuclear Weapons],” Renmin Ribao, 13 September 1990, via: www.xinhuanet.com.

- “中国政府原则决定参加不扩散核武器条约 [The Chinese Government Decides in Principle to Join the NPT],” Renmin Ribao, 11 August 1991, via: www.xinhuanet.com.

- People’s Republic of China, “Instrument of Accession to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons,” 11 March 1992.

- Mingquan Zhu, “The Evolution of China’s Nuclear Nonproliferation Policy,” The Nonproliferation Review, vol. 4, no. 2, Winter 1997, pp. 40-48.

- Permanent Mission of the People’s Republic of China to the United Nations, “胡锦涛主席在安理会核不扩散和核裁军峰会上的讲话 [Statement by President Hu Jintao at the United Nations Security Council Summit on Nuclear Non-proliferation and Nuclear Disarmament],” 24 September 2009, www.china-un.org.

- Bill Gertz, “China Nuclear Transfer Exposed: Hill Expected to Urge Sanction,” The Washington Times, 5 February 1996, via: http://web.lexis-nexis.com.

- Joby Warrick and Peter Slevin, “Libyan Arms Designs Traced back to China: Pakistanis Resold Chinese-Provided Plans,” The Washington Post, 15 February 2004, p. A01, www.washingtonpost.com.

- Alistair Ian Johnston, “Prospects for Chinese Nuclear Force Modernization: Limited Deterrence versus Multilateral Arms Control,” China Quarterly, June 1996, pp. 552-558.

- “Statement of Admiral Samuel J. Locklear, U.S. Navy Commander, U.S. Pacific Command Before the Senate Committee on Armed Services on U.S. Pacific Command Posture,” Senate Armed Services Committee, 25 March 2014, p.10, www.armed-services.senate.gov.

- U.S. Department of Defense, “Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China,” April 2013, www.defense.gov.

- Lin Shu-yuan, “Taiwan, China to Enhance Cooperation in Nuclear Safety,” Central News Agency (Taiwan), 5 April 2011.