The CNS North Korea Missile Test Database

A collection of missile tests including the date, time, missile name, launch agency, facility name, and test outcome.

Indonesia does not possess nuclear, biological, or chemical weapons, and is a member in good standing of most relevant nonproliferation treaties and organizations. [1]

As an active participant of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), Indonesia has been critical of those non-universal nonproliferation mechanisms that potentially limit the access of non-nuclear weapon States (NNWS) to technologies for the peaceful uses of nuclear energy. Although Indonesia, a prominent member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), supports the Southeast Asian Nuclear-Weapons-Free-Zone (SEANWFZ) and the ASEAN Network of Regulatory Bodies on Atomic Energy (ASEANTOM), Jakarta remains skeptical of multilateral export control regimes. Indonesia has generally viewed them as supply cartels that impede the flow of technology to the developing world, including the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG), the Australia Group, the Wassenaar Arrangement, and the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR). On 20 September 2017, Indonesia signed the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. [2]

Indonesia has a nascent export control system and does not maintain control lists for most dual-use items. Indonesia’s leadership is looking to foreign partners—including the United States, the European Union, and Japan—to help with implementation of UN Security Council Resolution 1540, and especially the strengthening of its dual-use control lists. [3] Although Indonesia actively cooperates with neighboring Singapore and Malaysia on maritime security issues, Jakarta has not agreed to participate in the U.S.-led Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI), due to concerns that PSI-related activities could encroach on its national sovereignty, and its belief they may contradict the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. [4]

Indonesia does not possess a nuclear weapons program, although President Sukarno, Indonesia's leader from 1945 to 1967, considered the option in the mid-1960s. [5] After Sukarno's removal from power in 1967, the Indonesian government agreed to a Comprehensive Safeguards Agreement for its fledgling nuclear facilities, marking the beginning of Indonesia’s role as a proponent of the peaceful uses of nuclear technology. In 1970, Indonesia signed the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) as a non-nuclear weapon state, ratifying it in 1979. [6] Indonesia acceded to the Additional Protocol in 1999, becoming the first state in Southeast Asia to be bound by this more rigorous verification mechanism. [7] Indonesia is a member of the Treaty on the Southeast Asia Nuclear Weapon-Free Zone (the Bangkok Treaty), which entered into force in 1997. Indonesia signed the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) in 1996, ratifying it in February 2012. [8] Indonesia began implementation of the IAEA Integrated Safeguards, including the additional protocol, in 2003. [9]

Indonesia continues to advocate strongly for the protection of the rights of non-nuclear weapon States to peaceful uses of nuclear technology. Jakarta issued a statement at the 2010 General Conference of the IAEA in support of the newly created ASEAN Regulatory Network (ASEANTOM), which facilitates collaboration for the security of the peaceful use of nuclear technology. [10] In November 2013, Indonesia hosted the 4th Asia-Pacific Safeguards Network and held the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty – Regional Conference for States in Southeast Asia, the Pacific and the Far East in May 2014. [11] In February 2018, the IAEA and Indonesia signed a practical arrangement promoting enhanced peaceful nuclear technology cooperation among developing countries. [12]

Indonesia has taken an active role in nuclear safety and security, and is a signatory to the Joint Convention on the Safety of Spent Fuel Management and on the Safety of Radioactive Waste Management, the Convention on Nuclear Safety, and the Convention on the Physical Protection of Nuclear Material. With the cooperation of the IAEA, Indonesia has installed seven Radiation Portal Monitors (RPMs) at its main harbors of Batam, Balawan, Makassar, Bitung, Tanjung Priuk, Tanjung Perak, and Semarang. [13] In 2016, with the cooperation of the U.S. Department of Energy, Indonesia down-blended its remaining stock of highly enriched uranium (HEU), making Southeast Asia entirely free of HEU. [14]

Indonesia’s nuclear energy agency, BATAN (Bandan Tenaga Nuklir Nasional), operates three nuclear research reactors in complexes on the island of Java: the Bandung Nuclear Complex, with a 2MWt TRIGA Mark II reactor; the Yogyakarta Nuclear Complex, with a 100kW Kartini TRIGA Mark II reactor; and the Serpong Nuclear Complex, which houses the 30MWt G.A. Siwabessy Multipurpose Research Reactor. [15]

Indonesia has long sought to develop nuclear power, but none of the proposed projects have gotten past the planning stages. In the 1990’s, BATAN identified 14 possible locations for nuclear power plants, yet many of the proposed sites proved controversial. [16] The controversy surrounding these sites highlighted two key challenges facing Indonesia's future nuclear development: concerns about placing facilities in areas prone to natural disasters such as earthquakes and volcanic eruptions and strong political opposition to nuclear energy.

Indonesia is not believed to have ever pursued the development of biological weapons (BW). Jakarta signed the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BTWC) in 1972, ratifying it in 1992. Indonesia participates regularly in meetings of BTWC state parties, and has hosted meetings on regional efforts to improve the treaty's implementation. [17] The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) reported in 2010 that Indonesia had yet to undertake any biotechnology research or development. Indonesia has taken a defensive stance with regard to biological weapons, forming a unit to combat bioterrorism in 2008 and later establishing a biodefense lab in 2010. [18]

Indonesia is not a member of the Australia Group. Jakarta has a growing medical and agricultural research industry, which could potentially present a proliferation risk if proper export controls are not put into place. [19] Currently, Indonesia relies on its domestic laws and regulations to manage the prevention and suppression of biological weapons, including the Penal Code, Law on Customs, Law on Animal, Fish and Plant Quarantine, Law Concerning Money Laundering Crimes, Law on the Eradication of Criminal Acts of Terrorism, and the Ministry of Industry and Trade Decree. [20] However, Indonesia is also in the process of drafting the Bill on the Implementation of the BWC. [21]

Indonesia is not known to have developed or to have attempted to procure chemical weapons-related materials. Indonesia became a signatory of the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) in 1993, ratifying it in 1998. In accordance with its CWC obligations, Indonesia controls chemicals listed within the treaty and additionally, enacted the Law of the Republic of Indonesia on the Use of Chemical Materials and the Prohibition of Chemical Materials as Chemical Weapons in 2008. [22] Indonesia also emphasizes the total destruction of chemical weapons by the remaining states in possession of CW as the main priority of Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), and is of the view that OPCW’s verification capabilities should be enhanced in order to increase confidence in the system. [23] In April 2014, Jakarta co-hosted a regional workshop on Article X of the CWC for Asian states party to the CWC focusing on regional cooperation and assistance. [24]

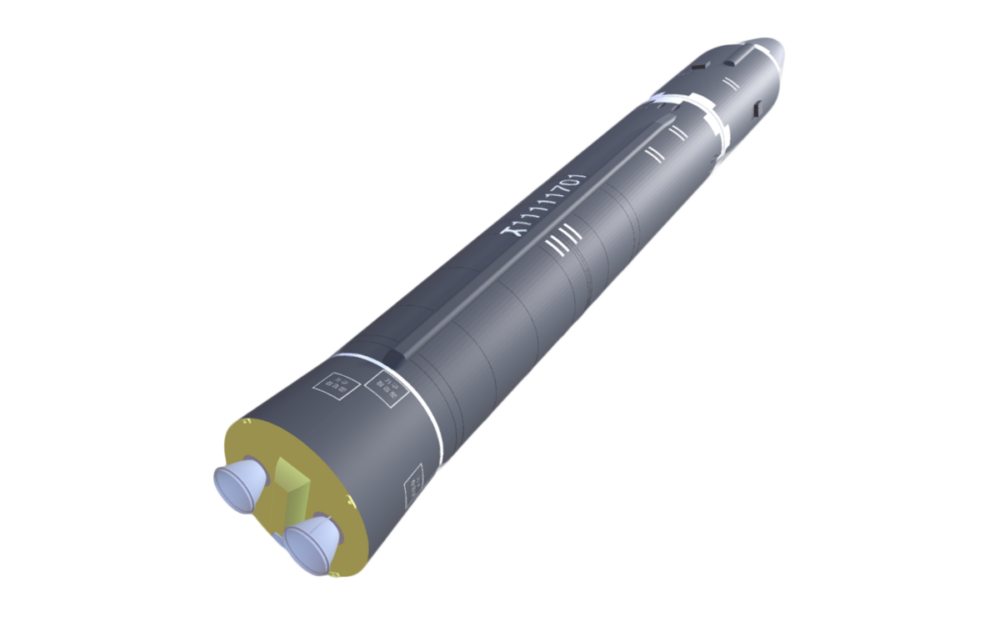

Indonesia is not a member of the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR), and does not have control lists covering dual-use materials as it is not a large producer of such items. Indonesia's navy and air force maintain a small inventory of air-to-air (AAMs) and surface-to-air (SAMs) missiles.

The Indonesian Air Force's (TNI-AU) inventory includes the U.S.-origin AIM-9P-4 and AGM-65 Maverick Sidewinder, as well as the Chinese QianWei-3. In March 2016, the United States approved the sale of 36 AIM-120c-7 Advanced Medium Range Air-to-Air Missiles (AMRAAMs) and missile guidance to Indonesia in a deal estimated at $97 million. [25] In October 2017, Indonesia contracted with Norwegian defense company Kongsberg for a complete Norwegian Advanced Surface to Air Missile System (NASAMS) worth an estimated $77 million. [26] The Indonesian Navy (TNI-AL) maintains a small number of C-802 and C-705 anti-ship missiles obtained from China, as well as French-origin AM 39 Exocet systems. [27]

Sources:

[1] Michael S. Malley and Tanya Ogilvie-White, "Nuclear Capabilities in Southeast Asia," The Nonproliferation Review, Spring 2009; and "Nuclear Safety in Southeast Asia: Issues, Challenges, and Regional Strategy," CSIS (Indonesia) Strategic Policy Report 2010.

[2] “List of Countries Which Signed Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons,” United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs, accessed 21 February 2018, www.un.org.

[3] Discussions between CNS researcher Stephanie Lieggi and Indonesian government officials, Jakarta, February 2011.

[4] Charles Wolf, Jr., "Asia's Nonproliferation Laggards: China, India, Pakistan, Indonesia and Malaysia," Wall Street Journal, 9 February 2009; and Stephanie Lieggi, "Proliferation Security Initiative Exercise Hosted by Japan Shows Growing Interest in Asia But No Sea Change in Key Outsider States," WMD Insights (December 2007 to January 2008), www.wmdinsights.com.

[5] Sukarno officially had only one name; this is not uncommon in Indonesia. For more on Sukarno's interest in nuclear weapons, see Robert M. Cornejo, "When Sukarno Sought the Bomb: Indonesian Nuclear Aspirations in the Mid-1960s," The Nonproliferation Review, Summer 2000.

[6] "Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty: Status of Treaty," Indonesia entry, Accessed 1 March 2011, www.un.org.

[7] "Status of Additional Protocols," International Atomic Energy Agency, 20 December 2010, www.iaea.org.

[8] For more background see: Sean Dunlop and Gaukhar Mukhatzhanova, "Indonesia Takes the Lead on the CTBT," CNS Feature Story, 4 May 2010, www.nonproliferation.org.

[9] Mutiara Solichah, “Implementation of Integrated Safeguards in Indonesia,” Directorate Inspection Installation and Nuclear Material – Nuclear Energy Regulatory Agency, IAEA-CN-184/334, 2010, www.iaea.org.

[10] H. E. Rachmat Budiman, “Statement by H.E. Rachmat Budiman at the 57th Annual Regular Session of the General Conference of the IAEA,” 16-20 September 2013, www.iaea.org.

[11] H. E. Rachmat Budiman, “Statement by H.E. Rachmat Budiman at the 57th Annual Regular Session of the General Conference of the IAEA,” 16-20 September 2013, www.iaea.org.

[12] Aabha Dixit, “IAEA Director General Visits Indonesia: Highlights Close Cooperation in Using Nuclear Technology,” 9 February 2018, www.iaea.org.

[13] “National Progress Report: Indonesia,” Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, 31 March 2016, www.belfercenter.org.

[14] “NNSA Announces Elimination of Highly Enriched Uranium (HEU) From Indonesia,” National Nuclear Security Administration, 29 August 2016, nnsa.energy.gov.

[15] "Preventing Nuclear Dangers in Southeast Asia and Australasia," IISS Strategic Dossier, September 2009, pp. 65-66, www.iiss.org.

[16] Discussions between CNS researcher Stephanie Lieggi and Indonesian nuclear agency officials, February 2011; see also Richard Tanter, Arabella Imhoff, and David Von Hippel, "Nuclear Power, Risk Management and Democratic Accountability in Indonesia: Volcanic, Regulatory and Financial Risk in the Muria Peninsula Nuclear Power Proposal," The Asia-Pacific Journal, 21 December 2009, www.japanfocus.org.

[17] "Transcription of the Statement Given by Indonesia to the BTWC 2007 Meeting of Experts," 20 August 2007, via: www.brad.ac.uk.

[18] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, “OECD Existing Chemicals Database,” http://webnet.oecd.org.

[19] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, “OECD Existing Chemicals Database,” http://webnet.oecd.org.

[20] "Strategic Weapons System, Indonesia," Jane's Sentinel Security Assessment, 8 October 2010.

[21] "Indonesia Legislative Database," United Nations, Accessed 3 August 2011, www.un.org.

[22] "Disarmament and Non-Proliferation of Biological Weapons," Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Indonesia, 7 July 2010, www.deplu.go.id.

[23] "Disarmament and Non-Proliferation of Chemical Weapons," Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Indonesia, 7 July 2010, www.deplu.go.id.

[24] Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, "Regional Workshop Held in Indonesia on Article X and Cooperation in Assistance and Emergency Response," 15 April 2014, www.opcw.org.

[25] Franz-Stefan Gady, “US Clears Sale of Advanced Missiles to Indonesia,” The Diplomat, 18 March 2016, www.thediplomat.com.

[26] Mike Yeo, “Indonesia Strikes $77M Deal for Air-Defense System by Norway’s Kongsberg,” Defense News, 1 November 2017, www.defensenews.com.

[27] "Navy, Indonesia," Jane's Sentinel Security Assessment, 12 January 2011.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest on nuclear and biological threats.

A collection of missile tests including the date, time, missile name, launch agency, facility name, and test outcome.

At this critical juncture for action on climate change and energy security, 20 NGOs from around the globe jointly call for the efficient and responsible expansion of nuclear energy and advance six key principles for doing so.

Information and analysis of nuclear weapons disarmament proposals and progress in Belarus