North Korea Chemical Overview

Background

This page is part of the North Korea Country Profile.

- Click for Recent Developments and Current Status

North Korea claims that it does not possess chemical weapons (CW). While assessing CW stockpiles and capabilities are difficult, the DPRK is thought to be among the world’s largest possessors of chemical weapons, ranking third after the United States and Russia. 1 In 2012, the South Korean Ministry of National Defense (MND) estimated that the DPRK possesses between 2,500 and 5,000 metric tons of chemical weapons. 2

According to the South Korean MND, over 70% of North Korea’s ground forces, supported by thousands of artillery systems, are deployed within 90 miles of the DMZ. 3 The U.S. Department of Defense has described this as an “offensively oriented posture.” 4 South Korean daily Chosun Ilbo, reported in 2002 that chemical weapons were suspected to be among those deployed near the DMZ in forward units. 5 Chemical weapons could potentially be used in the early stages of an attack to debilitate key metropolitan areas in South Korea. 6

North Korea remains one of the few countries not to have signed or acceded to the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC). North Korea has signed the Geneva Protocol, which prohibits the use of CW in warfare, but does not prevent a state from producing or possessing them. 7 The DPRK refused to acknowledge having chemical weapons as called for by UN Security Council Resolution 1718, which was passed in October 2006 following North Korea’s underground nuclear test.

Capabilities

North Korea may possess between 2,500 and 5,000 tons of CW agents. 8 The South Korean government assesses that North Korea is able to produce most types of chemical weapons indigenously, although it must import some precursors to produce nerve agents, which it has done in the past. 9 At maximum capacity, North Korea is estimated to be capable of producing up to 12,000 tons of CW. Nerve agents such as Sarin and VX are thought be to be the focus of North Korean production. 10

According to the government-sponsored Korea Research Institute of Chemical Technology [한국화학연구원] in South Korea, North Korea has four military bases equipped with chemical weapons, 11 facilities where chemical weapons are produced and stored, and 13 dedicated research and development facilities. 11 Two facilities near the cities of Kanggye and Sakchu are reportedly equipped to prepare and fill artillery shells with CW agents. These two locations also allegedly test agents, possibly in large underground facilities. 12 However, there has been no open source evidence of new storage facilities. 13

North Korea’s weak economy has resulted in severe shortages of both energy and raw materials, making estimating the country’s CW production levels even more difficult. 14 It is possible that Pyongyang is allowing its existing CW cache to age due to these economic circumstances, which could make them unreliable on the battlefield — if usable at all. This may be particularly true of what is thought to be the majority of the DPRK’s cache: unitary munitions which hold a single canister of lethal chemicals, rather than the more stable binary system, holding two or more stable chemicals which are combined at deployment. 15

Nevertheless, North Korea has a considerable and capable, albeit aging, chemical industry able to produce dual-use chemicals such as phosphate, ammonium, fluoride, chloride, and sulfur. 16 In recent years, the DPRK has continued to acquire dual-use chemicals that could potentially be used in its CW program from abroad (China, Thailand, Malaysia). 17

North Korea is believed to be capable of deploying its stockpile of chemical agents through a variety of means, including field artillery, multiple rocket launchers, FROG rockets, Scud and Nodong missiles, aircraft and unconventional means. 18 Additionally, U.S. military authorities believe there is long-range artillery deployed in the DMZ, along with ballistic missiles capable of delivering chemical warfare agents. 19

History

In the aftermath of the Korean War and in light of the perceived nuclear threat from the United States, North Korea sought a less costly alternative to nuclear weapons. 20 An indigenous chemical industry and chemical weapons production in North Korea have their roots in the ‘Three Year Economic Plan’ that spanned the years from 1954 to 1956, the period immediately following the Korean War, and the first ‘Five Year Plan’ from 1957 to 1961. However, significant progress was not made until the first ‘Seven Year Plan’ (1961-67). 21 At that time, Kim Il Sung issued a “Declaration for Chemicalization” whose aim was to further develop an independent chemical industry capable of supporting various sectors of its economy, as well as support chemical weapons production. 22 The DPRK established the basic organization of the current Nuclear and Chemical Defense Bureau at this time. 23

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, the DPRK received assistance from both the Soviet Union and China in developing its nascent chemical industry. The U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) estimated in May 1979 that the DPRK had only a defensive CW capability. 24 Estimates vary as to when North Korea is believed to have acquired the capability for independent CW production. Some sources suspect it was not until the early 1980s, and others speculate it was as early as the 1970s. 25 By the late 1980s, the DPRK was capable of producing substantial amounts of CW agents and deployed a large number of chemical weapons munitions. 26 In January 1987, the South Korean MND reported that the DPRK possessed up to 250 metric tons of chemical weapons, including Mustard (blister agent), and some nerve agents. 27 By 2010, the MND’s estimate had climbed to 2,500 to 5,000 metric tons of chemical agents, including nerve agents. 28

Scarcity Requires External Sources

During the 1990s, DPRK was forced to turn to foreign sources for precursors required in manufacturing nerve agents. In 1996, an employee of a Kobe, a Japan-based trading company, was caught trying to export 50 kg of sodium fluoride and 50 kg of hydrofluoric acid to North Korea via North Korean cargo vessels. Japanese authorities arrested the individual and charged him with illegally trading chemicals for weapons production, specifically, Sarin. 29

It came to light in the fall of 2004 that China and Malaysia had exported to North Korea in the previous year without government approval, a considerable amount — more than 100 tons in one case – of sodium cyanide, a dual-use chemical that could be used to manufacture both hydrogen cyanide (blood agent) and Tabun (nerve agent). In the case of China, South Korea had originally exported the chemicals, which China then re-exported to North Korea. Another such attempt via Thailand was reportedly thwarted. 30

North Korea and the Chemical Weapons Convention

Since 1997, the ROK government has been unsuccessful in convincing the DPRK to join the CWC. 31 The DPRK has also rebuffed similar efforts on the part of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) and the Japanese government. 32 In theory, North Korea’s accession to the CWC could convey long-term economic advantages for the DPRK through treaty-controlled chemical and technology trade. In the short term, however, North Korea is not likely to join the CWC regime. 33

Allegations of Human Testing

Activists, North Korean defectors, and the South Korean government have reported charges of chemical weapons experimentation on humans. However, no publicly available evidence has substantiated the allegations. 34 In 1994, the South Korean National Unification Board reported to the National Assembly that Pyongyang was testing CW on its political prisoners. 35 In 2004, a BBC-produced documentary titled “Access to Evil” alleged that the DPRK had tested CW on its political prisoners. However, numerous discrepancies in the film questioned its veracity. 36 In response to the documentary, South Korea seemed to demur on its previous assertions. A spokeswoman for South Korea’s Unification Ministry said, “We have no official comment on whether humans were used for tests…there are areas [of the documentary] that are not completely free of doubt.” 37 Activists have asserted that the South was being diplomatic in order to avoid confrontation with the North. In 2013, Human Rights in North Korea, citing defector testimony, alleged that the DPRK was testing CW on political prisoners and disabled children at Detention Camp 22 (Hoeryong Concentration Camp) and an island off South Hamgyong Province. 38 In February 2014, the United Nations Human Rights Council reported accounts of CW use on disabled persons; however it could not independently verify the accuracy. 39

Recent Developments and Current Status

While there is no evidence that North Korea’s CW program is growing, South Korea continues to take the threat seriously. A month after North Korea shelled Yeonpyeong Island, killing civilians with conventional munitions, the South Korean National Emergency Management Agency distributed 1,300 gas masks to residents of islands along the disputed western border, as well as an additional 610,000 to boost numbers amongst the 3.93 million civil defense corps members. The Agency also said it would renovate existing emergency shelters located at subway stations and underground parking lots to protect against chemical weapons. 40 These efforts seem to assuage fear more than anything else, as gas masks cannot protect against blister agents that affect the skin such as Mustard, Lewisite, and Phosgene oxime, which North Korea is believed to possess. In October 2013, the U.S. and South Korea agreed to build a joint surveillance system to detect biochemical agents along the demilitarized zone. This agreement will also enable information sharing on vaccines and diseases. 41

North Korea may have contributed to Syria’s chemical weapons program. In 2009, Greece seized 14,000 chemical suits from a North Korean ship believed to have been bound for Syria. In April 2013, Turkish authorities seized small arms, ammunition, and gas masks from a ship flying under the Libyan flag. According to the captain of the ship, the cargo came from North Korea and was to be transported from Turkey to Syria over land. 42 In February 2018, a leaked report from the UN Panel of Experts found that North Korea had supplied the Syrian regime of Bashar al-Assad with equipment which can be used in the production of chemical weapons, including acid-resistant tiles, valves and thermometers. 43

On 13 February 2017, Kim Jong-nam, the half-brother of DPRK leader Kim Jong-un, was attacked from behind by two women at the Kuala Lumpur airport, who wiped his face with cloths. He died on the way to the hospital, after complaining of pain in his face and having a seizure 44. Following an investigation, Malaysian authorities announced that Jong-nam had been killed using the chemical nerve agent VX. 45 Police hypothesize that each woman had a different compound of VX on their cloths, harmless individually but deadly when combined. 46 On 10 October 2017, a Malaysian government chemist testified that the concentration of VX found on Kim Jong-nam’s skin was 1.4 times greater than the median lethal dose. 47

North Korea rejected claims that it was behind the assassination, instead citing the attack as a conspiracy between Malaysia and South Korea. 48 On 6 March, 2018, the United States imposed additional sanctions on North Korea under the Chemical Weapons and Biological Weapons Control Act of 1991, having come to the determination that the North Korean government was responsible for Kim Jong-nam’s assassination using VX. 49

Stay Informed

Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest on nuclear and biological threats.

Glossary

- Chemical Weapon (CW)

- The CW: The Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons defines a chemical weapon as any of the following: 1) a toxic chemical or its precursors; 2) a munition specifically designed to deliver a toxic chemical; or 3) any equipment specifically designed for use with toxic chemicals or munitions. Toxic chemical agents are gaseous, liquid, or solid chemical substances that use their toxic properties to cause death or severe harm to humans, animals, and/or plants. Chemical weapons include blister, nerve, choking, and blood agents, as well as non-lethal incapacitating agents and riot-control agents. Historically, chemical weapons have been the most widely used and widely proliferated weapon of mass destruction.

- Chemical Weapon (CW)

- The CW: The Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons defines a chemical weapon as any of the following: 1) a toxic chemical or its precursors; 2) a munition specifically designed to deliver a toxic chemical; or 3) any equipment specifically designed for use with toxic chemicals or munitions. Toxic chemical agents are gaseous, liquid, or solid chemical substances that use their toxic properties to cause death or severe harm to humans, animals, and/or plants. Chemical weapons include blister, nerve, choking, and blood agents, as well as non-lethal incapacitating agents and riot-control agents. Historically, chemical weapons have been the most widely used and widely proliferated weapon of mass destruction.

- Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC)

- The Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) requires each state party to declare and destroy all the chemical weapons (CW) and CW production facilities it possesses, or that are located in any place under its jurisdiction or control, as well as any CW it abandoned on the territory of another state. The CWC was opened for signature on 13 January 1993, and entered into force on 29 April 1997. For additional information, see the CWC.

- Geneva Protocol

- Geneva Protocol: Formally known as the Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use in War of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or Other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare, this protocol prohibits the use in war of asphyxiating, poisonous, or other gases, and bans bacteriological warfare. It was opened for signature on 17 June 1925. For additional information, see the Geneva Protocol.

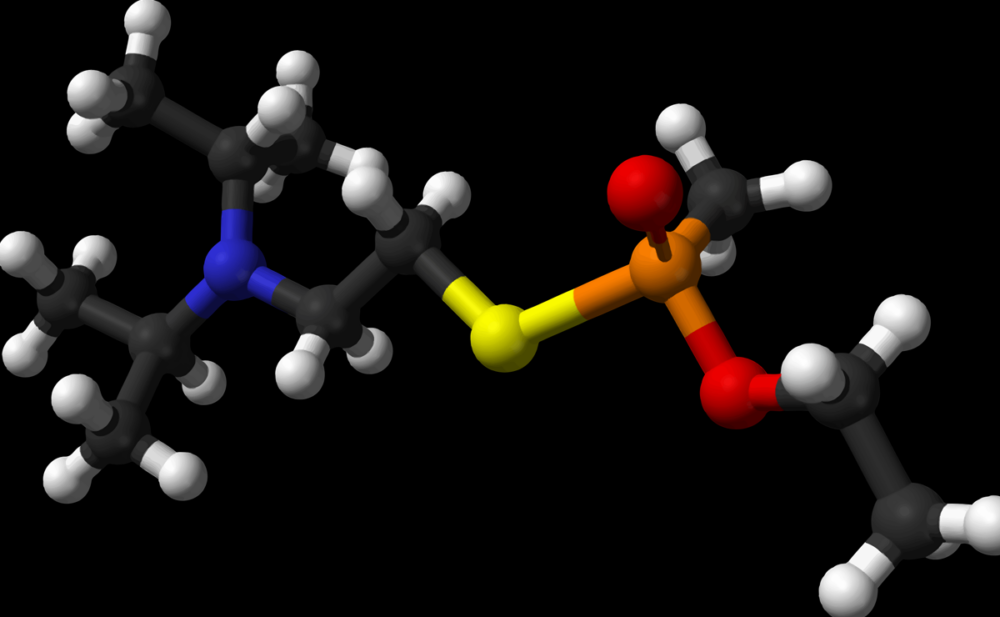

- Nerve agent

- A nerve agent is a chemical weapon that attacks the human nervous system, leading to uncontrolled nerve cell excitation and muscle contraction. Specifically, nerve agents block the enzyme cholinesterease, so acetylcholine builds up in the nerve junction and the neuron cannot return to the rest state. Nerve agents include the G-series nerve agents (soman, sarin, tabun, and GF) synthesized by Germany during and after World War II; the more toxic V-series nerve agents (VX, VE, VM, VG, VR) discovered by the United Kingdom during the 1950s; and the reportedly even more toxic Novichok agents, developed by the Soviet Union between 1960 and 1990. The development of both the G-series and V-series nerve agents occurred alongside pesticide development.

- Sarin (GB)

- Sarin (GB): A nerve agent, sarin causes uncontrollable nerve cell excitation and muscle contraction. Ultimately, sarin victims suffer death by suffocation. As with other nerve agents, sarin can cause death within minutes. Sarin vapor is about ten times less toxic than VX vapor, but 25 times more toxic than hydrogen cyanide. Discovered while attempting to produce more potent pesticides, sarin is the most toxic of the four G-series nerve agents developed by Germany during World War II. Germany never used sarin during the war. However, Iraq may have used sarin during the Iran-Iraq War, and Aum Shinrikyo is known to have used low-quality sarin during its attack on the Tokyo subway system that killed 12 people and injured hundreds.

- VX

- VX: The most toxic of the V-series nerve agents, VX was developed after the discovery of VE in the United Kingdom. Like other nerve agents, VX causes uncontrollable nerve excitation and muscle excitation. Ultimately, VX victims suffer death by suffocation. VX is an oily, amber-colored, odorless liquid.

- Binary chemical weapon

- A munition in which two or more relatively harmless chemical substances, held in separate containers, react when mixed or combined to produce a more toxic chemical agent. The mixing occurs either in-flight, for instance in a chemical warhead attached to a ballistic missile or gravity bomb, or on the battlefield immediately prior to use. The mechanism has significant benefits for the production, transportation and handling of chemical weapons, since the precursor chemicals are usually less toxic than the compound created by combining them. Binary weapons for sarin and VX are known to have been developed; or

A munition containing two toxic chemical agents. The United Kingdom combined chlorine and sulfur chloride during World War I and the United States combined sulfur mustard and lewisite. This definition is less commonly used. - Dual-use item

- An item that has both civilian and military applications. For example, many of the precursor chemicals used in the manufacture of chemical weapons have legitimate civilian industrial uses, such as the production of pesticides or ink for ballpoint pens.

- Scud

- Scud is the designation for a series of short-range ballistic missiles developed by the Soviet Union in the 1950s and transferred to many other countries. Most theater ballistic missiles developed and deployed in countries of proliferation concern, for example Iran and North Korea, are based on the Scud design.

- Ballistic missile

- A delivery vehicle powered by a liquid or solid fueled rocket that primarily travels in a ballistic (free-fall) trajectory. The flight of a ballistic missile includes three phases: 1) boost phase, where the rocket generates thrust to launch the missile into flight; 2) midcourse phase, where the missile coasts in an arc under the influence of gravity; and 3) terminal phase, in which the missile descends towards its target. Ballistic missiles can be characterized by three key parameters - range, payload, and Circular Error Probable (CEP), or targeting precision. Ballistic missiles are primarily intended for use against ground targets.

- Nuclear weapon

- Nuclear weapon: A device that releases nuclear energy in an explosive manner as the result of nuclear chain reactions involving fission, or fission and fusion, of atomic nuclei. Such weapons are also sometimes referred to as atomic bombs (a fission-based weapon); or boosted fission weapons (a fission-based weapon deriving a slightly higher yield from a small fusion reaction); or hydrogen bombs/thermonuclear weapons (a weapon deriving a significant portion of its energy from fusion reactions).

- Mustard (HD)

- Mustard is a blister agent, or vesicant. The term mustard gas typically refers to sulfur mustard (HD), despite HD being neither a mustard nor a gas. Sulfur mustard gained notoriety during World War I for causing more casualties than all of the other chemical agents combined. Victims develop painful blisters on their skin, as well as lung and eye irritation leading to potential pulmonary edema and blindness. However, mustard exposure is usually not fatal. A liquid at room temperature, sulfur mustard has been delivered using artillery shells and aerial bombs. HD is closely related to the nitrogen mustards (HN-1, HN-2, HN—3).

- Blister agent

- Blister agents (or vesicants) are chemical agents that cause victims to develop burns or blisters (“vesicles”) on their skin, as well as eyes, lungs, and airway irritation. Blister agents include mustard, lewisite, and phosgene, and are usually dispersed as a liquid or vapor. Although not usually fatal, exposure can result in severe blistering and blindness. Death, if it occurs, results from neurological factors or massive airway debilitation.

- Hydrogen cyanide (AC)

- Hydrogen cyanide (AC): A blood agent, hydrogen cyanide (AC) harms its victims by entering the bloodstream and disrupting the distribution and use of oxygen throughout the body. This causes serious dysfunction in organ systems sensitive to low oxygen levels, such as the central nervous system, the cardiovascular system, and the pulmonary system. Hydrogen cyanide can be disseminated as a liquid, aerosol, or gas. Notoriously, Nazi Germany used hydrogen cyanide as a genocidal agent during the Holocaust.

- Blood agent

- Blood agents are chemical agents that enter the victim’s blood and disrupt the body’s use of oxygen. Arsenic-based blood agents do so by causing red blood cells to burst, and cyanide-based blood agents do so by disrupting cellular processing of oxygen. Arsine, cyanogen chloride (CK), and hydrogen cyanide (AC) are colorless gasses, while sodium cyanide (NaCN) and potassium cyanide (KCN) are crystalline. Hydrogen cyanide (CK) was used as a genocidal agent by Nazi Germany, and may have also been used by Iraq during the Iran-Iraq War and against the Kurdish city of Halabja. At high doses, death from cyanide poisoning occurs within minutes.

- Tabun (GA)

- Tabun (GA): A nerve agent, tabun was the first of the nerve agents discovered in Germany in the 1930s. One of the G-series nerve agents, Nazi Germany produced large quantities of tabun but never used it on the battlefield. Tabun causes uncontrollable nerve excitation and muscle contraction. Ultimately, tabun victims suffer death by suffocation. As with other nerve agents, tabun can cause death within minutes. Tabun is much less volatile than sarin (GB) and soman (GD), but also less toxic.

- Nerve agent

- A nerve agent is a chemical weapon that attacks the human nervous system, leading to uncontrolled nerve cell excitation and muscle contraction. Specifically, nerve agents block the enzyme cholinesterease, so acetylcholine builds up in the nerve junction and the neuron cannot return to the rest state. Nerve agents include the G-series nerve agents (soman, sarin, tabun, and GF) synthesized by Germany during and after World War II; the more toxic V-series nerve agents (VX, VE, VM, VG, VR) discovered by the United Kingdom during the 1950s; and the reportedly even more toxic Novichok agents, developed by the Soviet Union between 1960 and 1990. The development of both the G-series and V-series nerve agents occurred alongside pesticide development.

- Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW)

- The OPCW: Based in The Hague, the Netherlands, the OPCW is responsible for implementing the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC). All countries ratifying the CWC become state parties to the CWC, and make up the membership of the OPCW. The OPCW meets annually, and in special sessions when necessary. For additional information, see the OPCW.

Sources

- North Korean Security Challenges: A Net Assessment (London: The International Institute for Strategic Studies, 2011), p. 161.

- Republic of Korea Ministry of National Defense, Defense White Paper, 2014.

- Republic of Korea Ministry of National Defense, Defense White Paper, 2014.

- Department of Defense, "Proliferation: Threat and Response," Office of the Secretary of the Defense, January 2001, www.fas.org.

- Lee Kyo-Gwan, "리포트 -화학무기 전방부대 배치 완료 [NK Report - North Korea Completes Chemical Weapons Deployment in Forward Units]" Chosun Ilbo, 5 November 2002, www.chosun.com.

- "북한, 화학무기 생산능력 1일 15.2t [North Korea capable of manufacturing 15.2 tons per day of chemical weapons]" Yonhap News, 16 August 1997, www.yonhap.news.co.kr.

- The other countries who have not signed the CWC are: Egypt and South Sudan; "Status of Participation in the Chemical Weapons Convention as at 19 October 2015," Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons," www.opcw.org; "1925 Geneva Protocol (in alphabetical order)," United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs, http://unhq-appspub-01.un.org.

- Lee Yoon-Geol, "북한, 핵만큼 무서운 생화학무기 5천 t 보유 [North Korea has 5000 Tons of Chemical Weapons as Scary as Nuclear Weapons]," Sisa Journal, No 1121, 13 April 2011, www.sisapress.com; Republic of Korea Ministry of National Defense, Defense White Paper, 2014.

- "North Korea's Chemical and Biological Weapons Programs," Asia Report No. 167, International Crisis Group, 18 June 2009, www.crisisgroup.org; for further reading see: Eric Croddy, "Vinalon, the DPRK, and Chemical Weapons Precursors," NTI Issue Brief, February 2003, www.nti.org.

- Lee Yoon-Geol, "북한, 핵만큼 무서운 생화학무기 5천 보유 [North Korea has 5,000 Tons of Chemical Weapons as Scary as Nuclear Weapons]," Sisa Journal, No. 1121, 13 April 2011, www.sisapress.com.

- Kim Tae Hwan, "북한 생화학무기 시설 49곳, 화학무기만도 5천톤 보유 [North Korea has 5,000 Tons of Chemical Weapons and 49 CBW Facilities]," Newswire Korea, 17 October 2006, www.newswire.co.kr.

- Joseph S. Bermudez. Jr., "Asia, Inside North Korea's CW Infrastructure," Jane's Intelligence Review, 1 August 1996

- "North Korea's Chemical and Biological Weapons Programs," Asia Report No. 167, International Crisis Group, 18 June 2009, www.crisisgroup.org.

- Eric Croddy with Clarisa Perez-Armendariz and John Hart, Chemical and Biological Warfare: A Comprehensive Survey for the Concerned Citizen, (New York, NY; Springer-Verlag, 2002), p. 51; North Korean Security Challenges: A Net Assessment (London: The International Institute for Strategic Studies, 2011), pp. 161-162.

- "North Korea's Chemical and Biological Weapons Programs," Asia Report No. 167, International Crisis Group, 18 June 2009, www.crisisgroup.org.

- "North Korea's Chemical and Biological Weapons (CBW) Program," North Korea's Weapons Programs: A Net Assessment, The International Institute for Strategic Studies, 21 January 2004, p. 51, www.iiss.org.

- "North Korea's Chemical and Biological Weapons Programs," Asia Report No. 167, International Crisis Group, 18 June 2009, www.crisisgroup.org.

- Kwan Yang-Ju, "핵무기 못지않은 북한의 화학무기 폐기 방안 강구 긴요 [Strategy to Eliminate North Korea's Biological and Chemical Weapons Needed]," Northeast Asian Strategic Analysis, Korea Institute for Defense Analysis (KIDA), 7 October 2010; North Korean Security Challenges: A Net Assessment (London: The International Institute for Strategic Studies, 2011), p. 162.

- Department of Defense, "Proliferation: Threat and Response," Office of the Secretary of the Defense, January 2001.

- "North Korea's Chemical and Biological Weapons Programs," Asia Report No. 167, International Crisis Group, 18 June 2009, www.crisisgroup.org.

- Joseph S. Bermudez, Jr., "North Korea's Chemical and Biological Warfare Arsenal," Jane's Intelligence Review, 1 May 1993.

- Korea Institute for National Unification, "2009 북한개요 [2009 North Korea Summary]," 2009, p.109, www.kinu.or.kr; "North Korea's Chemical and Biological Weapons Programs," Asia Report No. 167, International Crisis Group, 18 June 2009, www.crisisgroup.org.

- "미국의 북한 생화학무기 압박 전략 [U.S. Strategy of Pressure on North Korean Biological, Chemical Weapons]," Shindonga, Donga Ilbo Magazine, November 2004, shindonga.donga.com.

- Joseph S. Bermudez, Jr., "North Korea's Chemical and Biological Warfare Arsenal," Jane's Intelligence Review, 1 May 1993.

- Joseph S. Bermudez, Jr., "North Korea's Chemical and Biological Warfare Arsenal," Jane's Intelligence Review, 1 May 1993; "North Korea's Chemical and Biological Weapons Programs," Asia Report No. 167, International Crisis Group, 18 June 2009; Lee Yoon-Geol, "북한, 핵만큼 무서운 생화학무기 5천 보유 [North Korea has 5,000 Tons of Chemical Weapons as Scary as Nuclear Weapons]," Sisa Journal, No. 1121, 13 April 2011, www.sisapress.com; "북한 생화학무기 대량생산 [North Korea Mass Producing Biological and Chemical Weapons]," Yonhap News Agency, 23 October 1992, www.yonhap.news.co.kr.

- Eric Croddy with Clarisa Perez-Armendariz and John Hart, Chemical and Biological Warfare : A Comprehensive Survey for the Concerned Citizen (New York; Springer-Verlag, 2002), pp. 50-51.

- "Defense Minister on DPRK Submarine, Rocket Test," The Korea Herald, 29 January 1987, p. 1.

- Republic of Korea Ministry of National Defense, Defense White Paper, 2010.

- "Trader Nabbed for Illegal Chemical Exports," Jiji Press Ticker Service, 8 April 1996, www.lexisnexis.com.

- "화학무기 원료 시안화나트륨 북유입 / 정부, 위험물질 북에 얼마나 갔는지 깜깜 [Chemical Weapon Precursor Exported to North Korea/Government Unsure about Amount Exported]," Donga Ilbo, 29 September 2004, www.donga.com; "Toxic Chemical Shipped to North Korea from South Korea," Agence France-Presse, 24 September 2004, www.lexisnexis.com.

- "South Korean Vice Foreign Minister Urges Pressure on North Over Chemical Arms," Yonhap News Agency, 7 May 1997, www.yonhapnews.co.kr.

- "Foreign Minister Urges Chemical Weapons Body to Deter North Korea," BBC Summary of World Broadcasts, 3 December 1998.

- "Why the Discrepancy Between ROK, DPRK Joint Communiqué Regarding Military Authorities Talks," Yonhap News Agency, 8 April 2002, www.yonhapnews.co.kr.

- Antony Barnett, "Revealed: the gas chamber horror of North Korea's gulag," The Guardian, 1 February 2004, www.guardian.co.uk; Joseph S. Bermudez. Jr., "Asia, Inside North Korea's CW Infrastructure," Jane's Intelligence Review, 1 August 1996.

- "North Korea Alleged Using Detainees in Chemical Weapons Tests," Associated Press, 26 September 1994.

- Bertil Lintner, "North Korea and the Poor Man's Bombs," Asia Times Online, 9 May 2007, www.atimes.com.

- Samuel Len, "Skepticism Over Gas Tests; Seoul to Await Probe After Report on North," International Herald Tribune, 3 February 2004, www.lexisnexis.com.

- David Hawk, “North Korea’s Hidden Gulag: Interpreting Reports of Changes in the Prison Camps,” Human Rights in North Korea, August 27, 2013; Julian Ryall, “North Korea ‘Testing Chemical Weapons on Political Prisoners,’” The Telegraph, 14 October 2013, www.telegraph.co.uk.

- UN Human Rights Council, "Report of the Detailed Finds of the Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea," A/HRC/25/CRP.1, p.93, 7 February 2014, www.un.org.

- "S. Korea to Guard Against N. Korea's Chemical Weapons," Agence France-Presse, 9 December 2010.

- “South Korea, US Agree to Build Anti-bioterrorism System,” Yonhap News Agency, 20 October 2013, http://yonhapnews.co.kr.

- Barbara Demick, “North Korea Tried to Ship Gas Masks to Syria, Report Says,” Los Angeles Times, 27 August 2013, http://articles.latimes.com; Joseph S. Bermudez, Jr., "North Korea's Chemical Warfare Capabilities," 38 North, 10 October 2013, 38north.org.

- Michael Schwirtz, “UN Links North Korea to Syria’s Chemical Weapons Program,” The New York Times, 27 February 2018, www.nytimes.com.

- David Bradley, "VX Nerve Agent in North Korean's Murder: How Does It Work?" Scientific American, 24 February 2017, www.scientificamerican.com.

- Richard C. Paddock and Choe Sang-Hun, "Kim Jong-nam Was Killed by VX Nerve Agent, Malaysians Say," The New York Times, 23 February 2017, www.nytimes.com.

- Richard C. Paddock, Choe Sang-Hun and Nicholas Wade, "In Kim Jong-nam's Death, North Korea Lets Loose a Weapon of Mass Destruction," The New York Times, 24 February 2017, www.nytimes.com; Cindy Vestergaard, “What are North Korea’s Chemical Weapon Capabilities,” Lowy Institute: The Interpreter, 24 April 2017, www.lowyinstitute.org.

- Trinna Leong, “VX nerve agent on Kim Jong Nam was 1.4 times the lethal dose: Malaysian chemist,” The Straits Times, 10 October 2017, www.straitstimes.com.

- David Bradley, "VX Nerve Agent in North Korean's Murder: How Does It Work?" Scientific American, 24 February 2017, www.scientificamerican.com.

- U.S. Department of State, Press Statement, Heather Nauert, Department Spokesperson, “Imposition of Chemical and Biological Weapons Control and Warfare Elimination Act Sanctions on North Korea,” 6 March 2018.