The CNS North Korea Missile Test Database

A collection of missile tests including the date, time, missile name, launch agency, facility name, and test outcome.

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), has maintained a bilateral security alliance with the United States since the Korean War (1950-1953). The ROK abandoned its nuclear weapons efforts in the 1970s, and is engaging in diplomatic efforts with North Korea and the United States to attempt to denuclearize the Korean peninsula. South Korea is a party to all major nonproliferation treaties and regimes, possesses ballistic and cruise missiles, and cooperates with the United States on missile defense.

South Korea first became interested in nuclear technology in the 1950s, but did not begin construction of its first nuclear power plant until 1971. [1] Changes in the international security environment influenced South Korea's decision to begin a nuclear weapons program in the early 1970s, but the ROK abandoned the effort under significant pressure from the United States. [2] In April 1975, South Korea signed the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT). [3] South Korea is also a party to the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) and is a member of the Nuclear Suppliers Group and the Zangger Committee. [4]

The United States deployed tactical nuclear weapons in South Korea from 1958 until 1991. [5] Afterward, South Korea focused its diplomatic efforts on keeping the Korean peninsula free of nuclear weapons. In January 1992, North and South Korea signed the Joint Declaration on the Denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula. In this agreement, North Korea and South Korea agreed not "to test, manufacture, produce, receive, possess, store, deploy or use nuclear weapons," and not to "possess nuclear reprocessing and uranium enrichment facilities." [6] However, both sides failed to implement the agreement's provisions relating to a bilateral inspections regime. [7] Despite North Korea’s violations of the Joint Declaration, including its multiple nuclear weapons tests, South Korea has never officially renounced its obligations under the declaration, and has called on the North to abide by the agreement. [8]

Beginning in 2003, South Korea participated in the Six-Party Talks, aimed at ending the nuclear crisis on the Korean Peninsula, until North Korea withdrew in 2009 over disagreements with the UN Security Council. [9] At the April 2018 Inter-Korean Summit, North and South Korean heads of state declared their aspiration for a “complete denuclearization” of the Korean Peninsula, echoing sentiments expressed 26 years earlier. [10]

South Korea’s civil nuclear sector is highly developed; 23 nuclear reactors supply a third of the country’s electricity. Two additional reactors are under construction. [11] Following President Moon Jae-in’s June 2017 announcement that South Korea would limit its use of nuclear energy moving forward, South Korea froze all ongoing construction and scrapped plans for future reactors. [12] Facing considerable public opposition, the Moon government restarted work on the two partially completed nuclear reactors in October 2017, but still plans to phase out nuclear power over the coming decades. [13]

South Korea ratified the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BTWC) in June 1987 and joined the Australia Group in October 1995. [14] Although South Korea possesses a well-developed pharmaceutical and biotechnology infrastructure, it has committed to pursue only defensive BW research and development. [15]

South Korea ratified the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) in April 1997. [16] At that time, South Korea reportedly confidentially declared possession of several thousand metric tons of chemical warfare agents and one chemical weapons (CW) production facility to the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW). Neither the OPCW nor South Korea has publicly acknowledged this declaration. The South Korean government has maintained a high level of secrecy regarding its previous chemical weapons activities, reportedly requiring the OPCW to refer to it in all documents as "another state party" or "an unnamed state party." However, media reports indicate that pursuant to its CWC obligations, the South Korean military built and operated a CW destruction facility to eliminate all CW munitions at a site in Yeongdong Chungcheong. [17]

Under the CWC, South Korea was obligated to eliminate its CW stockpile by April 2007. South Korea requested an extension on that deadline from the OPCW, reportedly citing a number of technical difficulties in the operation of its destruction facility. South Korea reportedly completed the destruction of its entire chemical weapons stockpile in July 2008, becoming the second CWC member to do. [18]

In the wake of the shelling of Yeonpyeong Island in November 2010, the South Korean government and the National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA) began to equip civilian facilities — such as subway stations — with gas and oxygen masks, as well as oxygen tanks, to be used in case of chemical attacks by North Korea. [19] Additionally, the U.S. chemical warfare battalion, which previously left South Korea in 2004, was redeployed to the Korean peninsula in 2013. [20]

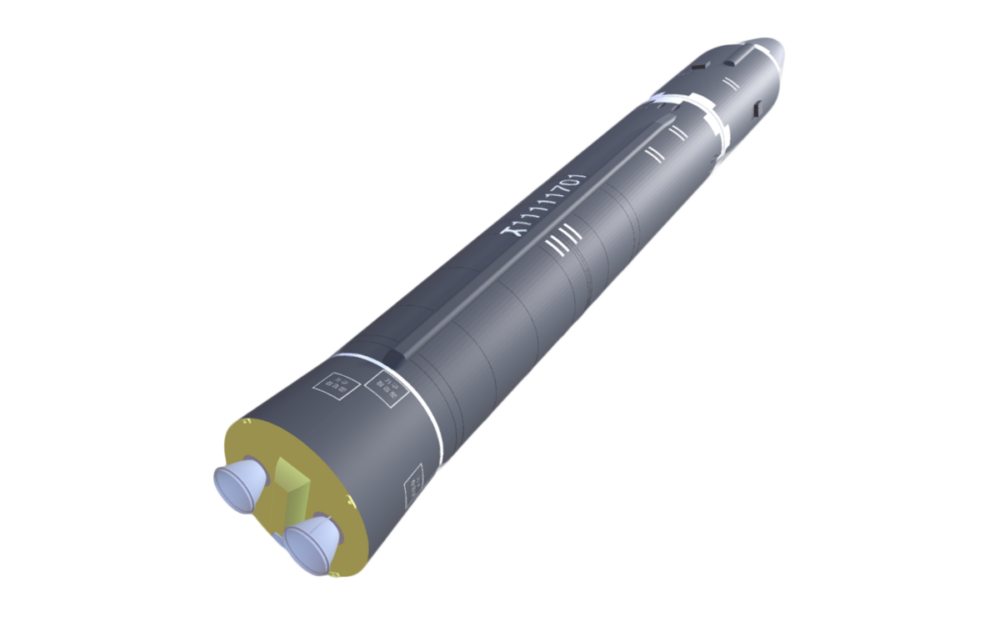

South Korea began developing missiles in the early 1970s, and successfully tested its first missile system NHK-1 (aka Baekgom-1), in September 1978. Currently, South Korea deploys a series of short-range ballistic missiles and several types of cruise missiles. South Korea joined the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR) in March 2001. [21] Until 2017, South Korea’s missile program was constrained by a series of bilateral agreements with the United States, which imposed range and payload restrictions on its indigenous missiles. In response to North Korea’s Unha-3 rocket launch in 2012, the United States and South Korea issued a new memorandum allowing South Korea to develop missiles ranging up to 800 kilometers, far enough to strike targets anywhere in North Korea. [22] In response to North Korean missile and nuclear tests in 2017, the United States and South Korea also agreed to lift restrictions on missile payloads. [23] In the 1990s, South Korea began development of a space program, including a space-launch vehicle (SLV). After numerous delays, South Korea successfully launched the two-stage KSLV-1 rocket on August 25, 2009. South Korea successfully placed a satellite into orbit in January 2013. [24]

In early 2017, the United States deployed two Terminal High Altitude Aerial Defense (THAAD) systems to South Korea, supplementing existing deployments of Patriot and Aegis missile defense systems in the region. [25] Despite a campaign pledge to remove the missiles, the Moon administration decided to continue THAAD deployments following North Korea’s ICBM tests in 2017. [26]

Sources:

[1] Ha Yeong-seon, 한반도의 핵무기와 세계질서 [Nuclear Weapons on the Korean Peninsula and World Order] (Seoul: Nanam, 1991).

[2] Larry A. Niksch, “U.S. Troop Withdrawal from South Korea: Past Shortcomings and Future Prospects,” Asian Survey 21 No. 3 (March 1981) pp. 325-34; Michael J. Siler, “U.S. Nuclear Nonproliferation Policy in The Northeast Asian Region During the Cold War: The South Korean Case,” East Asia 16, No. 3-4 (September 1998), pp 41-86; Etel Solingen, Nuclear Logics: Contrasting Paths in East Asia and the Middle East, (Princeton: The Princeton University Press, 2009) pp. 64 – 78.

[3] Daniel A. Pinkston, "South Korea's Nuclear Experiments," CNS Research Story, 9 November 2004, www.nonproliferation.org.

[4] United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs, "Status of Multilateral Arms Regulation and Disarmament Agreements," www.un.org; "Who are the Current NSG Participants?" Nuclear Suppliers Group, www.nuclearsuppliersgroup.org; "Members," Zangger Committee, 13 January 2010, www.zanggercommittee.org.

[5] ] Hans Kristensen and Robert S. Norris, “A History of US Nuclear Weapons in South Korea,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 73 No. 6 (October 2017) pp. 349-357; Roh Tae Woo, "President Roh Tae Woo's Declaration of Non-Nuclear Korean Peninsula Peace Initiatives," 8 November 1991, www.fas.org.

[6] "Korean Denuclearization Agreement," 20 January 1992, via: www2.law.columbia.edu.

[7] B.K. Kim, "Step-by-Step Confidence Building on the Korean Peninsula: Where Do We Start?" Institute for Science and International Security, Building Nuclear Confidence on the Korean Peninsula: Proceedings from the 23-24 July 2001 Workshop, p. 154, www.isis-online.org.

[8] "North Korea's Nuclear Tests," BBC, 12 February 2013, www.bbc.com; "Text of the Joint Statement," The New York Times, 19 September 2005, via: www.nytimes.com.

[9] Xiaodon Lian, "The Six Party Talks at a Glance," Arms Control Association, May 2012, www.armscontrol.org; Hyun-ju Ock, "No Six Party Talks without Progress: Korean Diplomat," The Korea Times, 16 June 2014, www.koreaherald.com; Mark Landler, “North Korea Says It Will Halt Talks and Restart Its Nuclear Program,” The New York Times, 14 April 2009, nytimes.com.

[10] “Full Text of Declaration Issued at Inter-Korean Summit,” Yonhap News, 27 April 2018, english.yonhapnews.co.kr.

[11] International Atomic Energy Agency, "Korea, Republic of," Power Reactor Information System Database, July 2017, http://pris.iaea.org.

[12] Jane Chung, “South Korea to resume building two new nuclear reactors, but scraps plans for 6 others,” Reuters, 24 October 2017, www.reuters.com.

[13] United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs, "Status of Multilateral Arms Regulation and Disarmament Agreements," www.un.org; "Australia Group Participants," www.australiagroup.net.

[14] Bureau of Arms Control, Verification, and Compliance, “2018 Report on Adherence and Compliance with Arms Control, Nonproliferation, and Disarmament Agreements and Commitments,” U.S. Department of State, April 2018, state.gov.

[15] Republic of Korea Ministry of National Defense, "2006 Defense White Paper," May 2007, p. 26, www.mnd.go.kr; Republic of Korea Ministry of National Defense, "2010 Defense White Paper," December 2010, www.mnd.go.kr; Republic of Korea Ministry of National Defense, "2012 Defense White Paper," December 2012, www.mnd.go.kr; Republic of Korea Ministry of National Defense, “2016 Defense White Paper,” 31 December 2016, www.mnd.go.kr.

[16] Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, "Member State – Republic of Korea," www.opcw.org.

[17] "Report: Korean Army Built Factory to Destroy Chemical Weapons," Deutsche Presse-Agentur, 9 May 2000.

[18] Chris Schneidmiller, "South Korea Completes Chemical Weapons Disposal," Global Security Newswire, 17 October 2008, www.nti.org.

[19] Lee Dong-young, "화생방 공격에도 6시간 '안전'… 500파운드 폭탄 터져도 '거뜬'," [6 Hours of Safety Even in the Case of Chemical Attacks… Safe Even with the Explosion of 500-pound Bomb], Dong-A Ilbo, 4 October 2011, http://news.donga.com.

[20] "U.S. Chemical Warfare Battalion to Return to Korea," Chosun Ilbo, 8 October 2012, http://english.chosun.com; Jon Rabiroff, "Chemical Weapon Unit Back in South Korea: Timing Coincidental," Stars and Stripes, 4 April 2013, www.stripes.com; Second Infantry Division, “23rd Chemical Battalion,” U.S. Army, 23 February 2018, www.2id.korea.army.mil.

[21] Lee Min-jung, "탄도미사일 사거리 연장되나 [Will the Missile Range be Extended for South Korea?]" EDAILY, 13 June 2012, www.edaily.co.kr; Missile Technology Control Regime, "MTCR Partners," www.mtcr.info.

[22] Choe Sang-Hun, “U.S. Agrees to Let South Korea Extend Range of Ballistic Missiles,” The New York Times, 7 October 2012, www.nytimes.com.

[23] U.S. Executive Office of the President, “Joint Press Release by the United States of America and the Republic of Korea” Press release, U.S. Executive Office, 8 November 2017, www.whitehouse.gov.

[24] Tong-hyung Kim, "Naro Rocket Blows Up in Midair," The Korea Times, 10 June 2010, www.koreatimes.co.kr; Jung-yoon Choi and Barbara Demick, "South Korea Launches Satellite into Orbit," The Los Angeles Times, 30 January 2013, www.latimes.com.

[25] Ian E. Rinehart, Steven A. Hildreth, and Susan V. Lawrence, “Ballistic Missile Defense in the Asia-Pacific Region: Cooperation And Opposition,” CRS Report 7-5700, Congressional Research Service, 3 April 2015.

[26] Michael Elleman, "North Korea Launches Another Large Rocket: Consequences and Options," 38 North, 10 February 2016; Alex Johnson, Stella Kim, Courtney Kube, “U.S. Begins Shipping Controversial Anti-Missile System to South Korea,” NBC News, 7 March 2017, www.nbcnews.com.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest on nuclear and biological threats.

A collection of missile tests including the date, time, missile name, launch agency, facility name, and test outcome.

At this critical juncture for action on climate change and energy security, 20 NGOs from around the globe jointly call for the efficient and responsible expansion of nuclear energy and advance six key principles for doing so.

Information and analysis of nuclear weapons disarmament proposals and progress in Belarus