Cole J. Harvey

Research Associate, The James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies

On March 29, 2010, the United States and India reached an agreement on the reprocessing of U.S.-obligated spent nuclear fuel in India, in accordance with the broader Agreement for Cooperation in the area of peaceful uses of nuclear energy that the two countries signed in August 2007. The reprocessing agreement allows India to separate plutonium from spent fuel from Indian reactors containing U.S.-origin nuclear material. In the past, only Japan and the member states of the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom) had been granted this consent in advance. In accordance with the agreement, both the reprocessing facilities and the nuclear material will be kept under IAEA safeguards and limited to peaceful uses. However, the ability to supplement its reactor fuel supply with plutonium fuel derived from imported uranium allows India to devote more of its domestically produced plutonium to military purposes.

Reprocessing is a chemical procedure by which spent fuel that has been removed from a nuclear reactor is broken down to separate plutonium and uranium from highly radioactive fission products, and other waste products such as the fuel's metal cladding. The extracted plutonium and uranium can be refashioned into reactor fuel and reused, increasing the amount of energy that can be drawn from a batch of fuel. The process also reduces the volume and level of radioactivity of the remaining waste that must be stored. However, since plutonium can be used as the fissile core of a nuclear weapon, access to reprocessing technology and expertise can be a pathway to nuclear proliferation. Indeed, the typical reprocessing method, known as PUREX, was first developed and deployed to produce plutonium for weapons. The procedure is now well-known, and employed by France, Japan, the United Kingdom, and India. Pakistan is also believed to operate a military reprocessing facility.[1] Though the United States formerly utilized reprocessing in its nuclear weapons program, it does not does not currently reprocess for any purpose, and has consistently encouraged other countries to do the same.

Owing to its status as a non-party to the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) and its 1974 "peaceful" nuclear test, India was isolated from nuclear trade and cooperation for 34 years. This isolation ended in 2008, when the 46-member Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) of exporting countries agreed to allow trade with India after a diplomatic push by the United States. The decision by the NSG, which waived the group's rule on supplying nuclear technology and materials to non-members of the NPT, opened the way for countries like France, Russia, and the United States to provide India with reactors and fuel in deals potentially worth billions of dollars.[2] Prior to the NSG waiver, India's nuclear industry was developed domestically with little outside aid. Now, however, India is looking to significantly expand its nuclear power generation with outside help. Speaking on February 18, 2008, special envoy of the Prime Minister Shri Shyam Saran stated that a "significant expansion" of India's nuclear power generation would require the "import of higher capacity reactors and uranium fuel."[3]

India possesses relatively little uranium, with around 54,000 tons of "reasonably assured resources."[4] India's nuclear power reactors require approximately 430 tons of natural uranium per year to operate at just 80 percent capacity. By contrast, it is estimated that India produces only 300 tons of uranium per year, and this figure must also supply fuel for India's weapons-grade plutonium production reactors (35 tons required) and feedstock for its uranium enrichment facilities (10 tons).[5] The strain of carrying out an expansion of nuclear power and maintaining a nuclear weapons program in the face of a tight domestic supply of uranium has led India to seek uranium fuel imports (following the NSG waiver) and it has for decades planned to develop a thorium-based nuclear fuel cycle.

India's thorium reserves are about six times as plentiful as its uranium reserves.[6] Thorium is not fissile itself, but can absorb a neutron to become uranium-233, which is fissile. The uranium-233 then fuels the reactor.

India's long-term goal has been to achieve a thorium-based fuel cycle in three stages. The first stage requires the production of plutonium in light-water reactors and pressurized heavy water reactors. The plutonium must be extracted from the spent fuel generated by these reactors via reprocessing. In the second stage, fast neutron reactors would be employed using plutonium to power the nuclear reaction, breeding fissile uranium-233 from a thorium blanket surrounding the core of the reactor. In the third stage, Advanced Heavy Water Reactors would burn the uranium-233 generated in stage two, along with additional plutonium and thorium.[7]

India currently operates nineteen power reactors, all but two of which are pressurized heavy water reactors, which utilize natural uranium as fuel.[8] Four more are under construction and twenty are planned, all of which are intended to come online in the next few years. Additionally, thirty-four reactors have been 'firmly proposed,' and are expected to be complete in the latter years of this decade and early 2020s.[9] India aims to nearly quintuple its generating capacity from approximately 4,000 MWe in 2010 to 20,000 MWe by 2020.[10] These targets are provided by India's Department of Atomic Energy,[11] and are considered overly optimistic by some observers. M.V. Ramana of Princeton University has written of the many challenges facing the Indian nuclear industry and concluded that "Despite media hype and continued government patronage, nuclear power is unlikely to contribute significantly to electricity generation in India for several decades.[12]

India's civilian nuclear industry must compete with its weapons program for supplies of fissile material. India is believed to possess approximately 70 nuclear weapons.[13] Similarly, regional rival Pakistan's arsenal is estimated at 70-90 weapons.[14]

General—The 2010 reprocessing agreement allows India to establish two new national reprocessing facilities to reprocess U.S.-origin spent fuel under IAEA safeguards.[15] Furthermore, the two parties agree to "pursue the steps necessary" to permit reprocessing at "one or more new additional national facilities in India," beyond the original two specified in the agreement.[16] Under the terms of the agreement, India must allow its reprocessing facilities to be monitored and placed under safeguards by the IAEA.[17] India's plutonium producing breeder reactor, however, will not be under IAEA safeguards.[18]

Security—The agreement obliges India to maintain physical protection at the facility at least to the level suggested by the IAEA in its recommendations on "The Physical Protection of Nuclear Material and Nuclear Facilities."[19] The IAEA document describes unirradiated plutonium, of the sort that would be produced at the Indian facilities, as a Category I material, representing the highest level of risk and deserving the highest level of security. Category I materials should be protected in an inner area, under constant surveillance when persons are present, monitored at all times by intrusion-detecting alarms, and protected by a 24-hour guard force.[20]

Management of plutonium—In managing the plutonium separated at the new facilities, India commits to "take into account the need to avoid contributing to the risks of nuclear proliferation; the need to protect the environment, workers and the public; the potential of the material for further energy generation; and the importance of balancing supply and demand, including demand for reasonable working stocks for civil nuclear operations."[21]

Suspension—Either party may suspend their participation in the agreement under "exceptional circumstances." Exceptional circumstances are limited to a determination by either party that the continued reprocessing of U.S.-origin nuclear material at the Indian facilities would result in a "serious threat to that Party's national security…or serious threat to the physical protection of the Facility" or the material inside.[22] However, the agreement can also be suspended by "Either Party's determination that suspension is an unavoidable measure," [23] meaning that the agreement can effectively be suspended for any reason.

Suspension of the agreement is valid for three months, but can be extended by the suspending party. In the event that suspension lasts for more than six months, India and the United States agree to enter into consultations "on compensation for the adverse impact on the Indian economy due to disruption in electricity generation…"[24]

Suspension of the agreement does not require India to discontinue operations at its reprocessing facilities, but India would be required to stop reprocessing U.S.-origin material.[25] Though the reprocessing agreement requires India to place those reprocessing facilities handling U.S.-origin nuclear material under IAEA safeguards, it does not discuss the termination of those safeguards. The termination of safeguards is governed instead by the India-specific safeguards agreement of July 9, 2008. The safeguards agreement, in turn, specifies that "The termination of safeguards on items subject to this Agreement shall be implemented taking into account the provisions of [IAEA document] GOV/1621."[26] The 1973 document, GOV/1621, stipulates that,

the rights and obligations of the parties…would continue to apply in connection with any supplied material or items and with any special fissionable material produced, processed or used in or in connection with any supplied material or items which had been included in the inventory, until such material or items had been removed from the inventory.[27]

Put plainly, the India-specific safeguards agreement requires safeguards to continue on imported nuclear material—or special fissionable material, such as plutonium, that is derived from imported uranium—until the material is removed from use.

In addition, the U.S.-India Agreement for Cooperation provides each party with a 'right of return' concerning any nuclear material or components transferred under the agreement and any special fissionable material produced by their use, meaning that the United States could choose to take possession of any plutonium that India developed from U.S.-origin fuel.[28]

According to the India-specific safeguards agreement, safeguarding of the reprocessing facilities themselves can only be terminated if India and the IAEA jointly determine that "that the facility is no longer usable for any nuclear activity relevant from the point of view of safeguards."[29] Without the IAEA's agreement, India cannot legally withdraw from civilian use the reprocessing facilities intended to handle U.S.-origin fuel and put them to work directly for a military program.

The suspension provisions in the Indian case are more relaxed than previous agreements with close U.S. allies. The U.S. agreement for cooperation with Euratom, which also gives advance consent for the reprocessing of U.S.-origin material, explicitly gives the United States a legal right to terminate the agreement and retake ownership of exported nuclear material if a member of Euratom conducts a nuclear test using U.S.-origin material. It also allows either party to end the agreement if the other side violates its safeguards obligations, or applies any material or equipment covered by the agreement to a military program.[30] Similar provisions apply in the U.S.-Japan agreement for cooperation, which allows the United States to end the agreement and implement its right of return if Japan detonates any nuclear device whatsoever.[31] There is no mention of compensation for any disruption to the European or Japanese economies that might arise from such an outcome; that provision is an innovation of the Indian reprocessing deal.

While the Euratom and Japanese agreements lays out specific circumstances under which they can be terminated, the decision to suspend or terminate the U.S.-India reprocessing agreement or broader agreement for cooperation would be a political one. A new Indian nuclear test would not automatically trigger either of the agreements' suspension protocols. However, the U.S. president could consider such a test so damaging to cooperation with India that suspension becomes an 'unavoidable measure.'

For India—The reprocessing agreement allows India to extend the benefits of the broader U.S.-India Agreement for Cooperation, once U.S. companies are able to export nuclear fuel and technology to India. Though the Agreement for Cooperation and the NSG waiver permit trade with India, New Delhi must still pass a nuclear liability law before U.S. firms can agree to develop reactors in India. Unlike French and Russian nuclear vendors, U.S. companies are privately owned and not backed by the resources of the state in the event of a reactor malfunction to results in property damage or loss of life. As a result, they are at a competitive disadvantage unless the importing country passes laws limiting a nuclear supplier's liability in the event of an accident. The liability law being discussed as of March 2010 would make reactor operators and the central government liable for damages resulting from a nuclear accident. Operators' liability would be limited to 5 trillion rupees, or approximately 100 million dollars. The state's liability would be limited to approximately 450 million dollars.[32] The low caps on liability have met with some resistance in the Indian parliament.[33] By contrast, the cleanup efforts following the relatively mild accident at Three Mile Island in 1979 cost roughly one billion dollars, and U.S. law holds operators accountable for up to 10 billion dollars in damages.[34] Once the liability law is passed, India has expressed interest in contracting with U.S. companies to construct and provide fuel for two reactors.[35]

Reprocessing the spent fuel that emerges from these reactors (and any others that receive U.S.-origin fuel) could allow India to increase the energy that it can extract from each batch of fuel, to ease its uranium shortage, and to advance on the three-stage path to the thorium fuel cycle. In addition, however, India will gain additional expertise in the separation of plutonium from spent fuel and large stocks of separated plutonium, both of which could be used in a military program if a political decision to do so is taken. It should be noted that spent fuel reprocessing is very expensive, and using reprocessed fuel in power reactors does not make economic sense at current uranium prices.[36]

In the broader sense, the agreement places India in an elite group of U.S. partners. Apart from India, only Euratom and Japan have advance consent from the United States to reprocess U.S.-origin spent fuel. The agreement indicates that the United States considers India a strategic partner, and values cooperation with India more highly than any potentially harmful proliferation effects the deal may engender.

The reprocessing agreement and the legal documents that buttress it (the Agreement for Cooperation and India-specific safeguards agreement), erect fairly formidable barriers against the use of U.S.-origin plutonium or uranium in the India weapons program. However, the deal could allow India to divert more of its domestic uranium to the weapons program while using imported material for the civilian sector.

In the region—The government of South Korea is seeking permission from Washington to reprocess its own U.S.-origin spent fuel. South Korea's goal is not primarily energy independence, but rather to reduce the volume of spent fuel that must be stored.[37] The potential proliferation concerns are the same, however. The decision to grant India the right to reprocess will make it more politically difficult for the United States to refuse South Korea's request. South Korea, its leaders will argue, is a party of the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty in good standing and a close ally of the United States. In other words, why should NPT non-party and nuclear-armed India and Japan, a non-weapons state, be granted the right to reprocess, but not South Korea?

The government of Pakistan has also expressed interest in developing an agreement for civil nuclear cooperation with the United States in the run-up to a high-level meeting in March in Washington. Pakistan, too, faces an underdeveloped civilian nuclear sector limited by NSG sanctions, continues to manufacture nuclear weapons, and is a partner with the United States. U.S. officials both in the Obama administration and in Congress were quick to point out that discussions of a U.S.-Pakistan nuclear cooperation agreement are "premature."[38]

In the wider nonproliferation context—The United States and its partners are concerned about the spread of uranium enrichment and spent fuel reprocessing technologies, known as 'sensitive technologies,' which can provide pathways to acquire nuclear weapons. Some developing states have charged that the U.S. push to waive NSG rules for India and permit reprocessing of U.S.-origin fuel there is a display of favoritism that weakens the NPT.

Speaking at a May 2009 meeting of the states-party to the NPT, Egypt—a leader of the Group of Non-Aligned States—noted that it "views with concern efforts by the Nuclear Suppliers Group and other discriminatory arrangements to impose additional restrictions on some but not on others, in a manner that is clearly politicized and does not contribute to the implementation of the NPT's objectives, in particular its universality…"[39] In another statement at the same meeting, Egypt asked with regard to sensitive technologies, "[M]ust we consider that what is irresponsible for one is responsible for another?"[40] As in the South Korean example above, the United States will find it more difficult to dissuade other countries from pursuing enrichment or reprocessing capabilities, when it has endorsed reprocessing in India, a nuclear-armed non-party to the NPT.

The reprocessing deal prohibits India from using U.S.-origin nuclear material in anything but a civilian setting. The deal allows India to reprocess spent fuel derived from U.S.-origin uranium—advance permission that only Euratom and Japan have previously been granted—but only in specific facilities under IAEA safeguards. The wider agreement for cooperation, under which the reprocessing agreement was negotiated, would allow the United States to require the return of any nuclear material (including plutonium) that had been exported under its terms, if the agreement were ever abrogated. While the reprocessing agreement does not list any specific circumstances under which cooperation must cease (such as, for example, a nuclear test by India), it does allow either party to suspend the agreement as a matter of judgment (the "unavoidable measure" clause).

However, the agreement does allow India to devote domestic uranium to the production of plutonium, easing the competition for resources between its civilian and military nuclear programs. Permitting India to reprocess U.S.-origin spent fuel also sets a potentially awkward example for a United States government that is committed to restraining the spread of reprocessing. Other U.S. partners, such as South Korea or even Pakistan, may press for Washington to bless their reprocessing programs.

Similarly, the reprocessing agreement could compound some states' objections to the original U.S.-India deal—namely, that the opening of nuclear trade with India weakens the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty by providing one of the benefits of membership in the treaty to a nuclear-armed non-party.

[1] Robert S. Norris and Hans M. Kristensen "Pakistani Nuclear Forces, 2009," Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, September/October 2009, https://thebulletin.metapress.com.

[2] See Cole Harvey, "Major Proposals to Strengthen the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty," Arms Control Association, March 2010. Page 15, www.armscontrol.org.

[3] Shri Shyam Saran, "India and the Nuclear Domain," February 18, 2008, https://mea.gov.in.

[4] "Nuclear Power in India," World Nuclear Association, March 30, 2010, www.world-nuclear.org.

[5] Zia Mian, A. H. Niyyar, R. Rajamaran, M. V. Ramana, "Plutonium Production in India and the U.S.-India Nuclear Deal," in Gauging U.S.-Indian Strategic Cooperation, Henry Sokolski, ed. Strategic Studies Institute, March 2007. p. 108-109, www.npec-web.org.

[6] "Thorium," World Nuclear Association, October 2009., www.world-nuclear.org.

[7] "Nuclear Power in India," World Nuclear Association, March 30, 2010., www.world-nuclear.org.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] "Meeting the Demand Projection," Department of Atomic Energy, Government of India, www.dae.gov.in.

[12] M.V. Ramana, "The Indian Nuclear Industry, Status and Prospects," Centre for International Governance Innovation, December 2009. Page 22, www.cigionline.org.

[13] Robert S. Norris and Hans M. Kristensen, "India's nuclear forces, 2008," Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, November/December 2008. Page 38, https://thebulletin.metapress.com.

[14] Robert S. Norris and Hans M. Kristensen "Pakistani Nuclear Forces, 2009," Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, September/October 2009, https://thebulletin.metapress.com.

[15] Article I, Paragraph 3 of the U.S.-India reprocessing agreement

[16] Article 1, Paragraph 4 of the U.S.-India reprocessing agreement

[17] Article 2 of the U.S.-India reprocessing agreement

[18] See "Agreement between the Government of India and the International Atomic Energy Agency for the Application of Safeguards to Civilian Nuclear Facilities," International Atomic Energy Agency, INFCIRC/754/Add.2, April 7, 2010, www.iaea.org.

[19] Article 4, paragraph 1 of the U.S.-India reprocessing agreement

[20] "The Physical Protection of Nuclear Material and Nuclear Facilities," INFCIRC/225/Rev.4 (Corrected), International Atomic Energy Agency, June 1999, www.iaea.org.

[21] Article 6, U.S.-India reprocessing agreement

[22] Article 7, paragraph 3, section i of the U.S.-India reprocessing agreement

[23] Article 7, paragraph 3, section ii of the U.S.-India reprocessing agreement

[24] Article 7, paragraph 7 of the U.S.-India reprocessing agreement

[25] Agreed Minute II, section iii, U.S.-India reprocessing agreement

[26] "Nuclear Verification, An Agreement with the Government of India for the Application of Safeguards to Civilian Nuclear Facilities," International Atomic Energy Agency, July 9, 2008. Paragraph 29.

[27] "The Formulation of Certain Provisions in Agreements Under the Agency's Safeguards System," International Atomic Energy Agency, GOV/1621, August 20, 1973.

[28] "Agreement for Cooperation between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of India Concerning Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Energy," August 3, 2007. Article 14 paragraph 4.

[29] "Nuclear Verification, An Agreement with the Government of India for the Application of Safeguards to Civilian Nuclear Facilities," International Atomic Energy Agency, July 9, 2008. Paragraph 32.

[30] "Agreement for Cooperation in the Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Energy between the European Atomic Energy Community and the United States of America," Article 13, www.carnegieendowment.org.

[31] "Agreement for Cooperation between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of Japan Concerning Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Energy," Article 12, www.carnegieendowment.org.

[32] "The Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage Bill, 2010," March 10, 2010, www.greenpeace.org.

[33] Anjana Pasricha, "India Defers Introduction of Civil Nuclear Liability Bill," Voice of America News, March 15, 2010, www1.voanews.com.

[34] Henry Sokolski, "Insuring India's Nuclear Power," The Wall Street Journal, April 19, 2010, https://online.wsj.com.

[35] Statement of William J. Burns, Undersecretary of State for Political Affairs, to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, September 18, 2008, https://foreign.senate.gov.

[36] See "The Economics of Reprocessing in the United States," Richard K. Lester, July 12, 2005, https://web.mit.edu. See also "Nuclear Reprocessing: Dangerous, Dirty, and Expensive," Union of Concerned Scientists, June 17, 2008, https://www.ucsusa.org.

[37] Cho Chung-un, "P.M. vows to develop nuclear fuel reprocessing technology," The Korea Herald, March 13, 2010, www.koreaherald.co.kr.

[38] Daryl Kimball, "Pakistan Presses Case for U.S. Nuclear Deal," Arms Control Today, April 2010, www.armscontrol.org.

[39] Statement by Maged Abdel Fatah Abdel Aziz, Egypt, at the 2009 Preparatory Committee meeting of the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty. May 4, 2009, www.reachingcriticalwill.org.

[40] Comments by the delegation of Egypt at the 2009 Preparatory Committee meeting of the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty, May 8, 2009, www.reachingcriticalwill.org.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest on nuclear and biological threats.

Understanding nuclear materials, including how plutonium and enriched uranium are produced, and the basics of nuclear energy and nuclear weapons, is the focus of this tutorial.

The economic, safety and proliferation risks of a civilian plutonium reprocessing capability. (CNS)

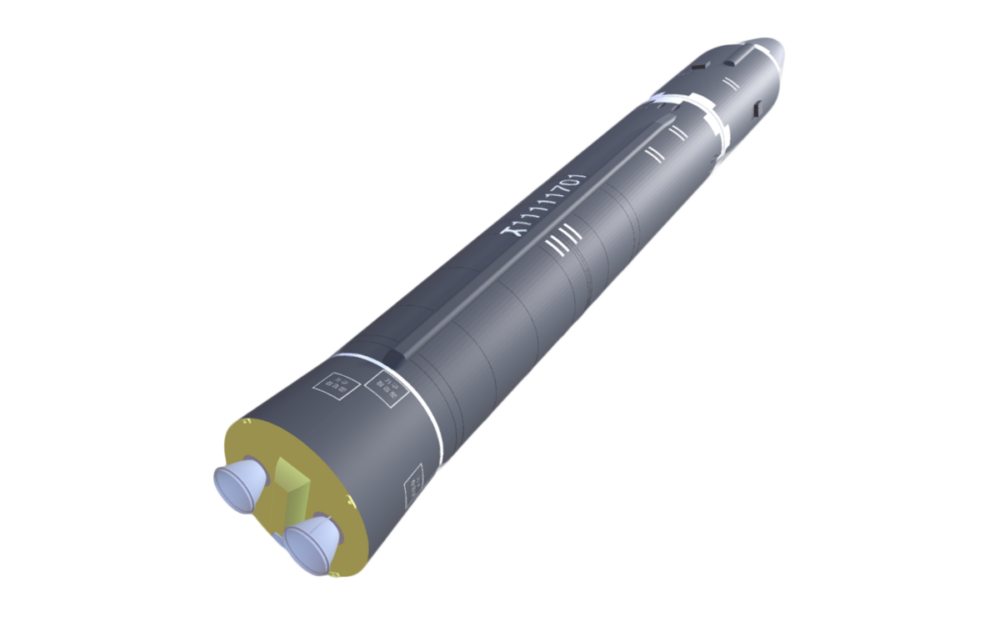

A collection of missile tests including the date, time, missile name, launch agency, facility name, and test outcome.