Ernest J. Moniz

Co-Chair and Chief Executive Officer, NTI

NTI Co-Chairs Ernest J. Moniz and Sam Nunn call on the United States to resume a position of global leadership to reduce the risks posed by nuclear weapons. Their recommendations–which are further elaborated and reinforced in seven related policy papers by NTI experts–include proposals for changes to U.S. nuclear policy and posture, reengagement with Russia on a range of stategic stability and arms control issues, sustained dialogue and nuclear risk reduction measures with China, and recommitment to multilateral efforts to strengthen the global nonproliferation regime.

Chapter 1

By Ernest J. Moniz and Sam Nunn

Fortunately, most Americans do not lie awake at night in fear of nuclear war; yet, the unsettling realityis that nuclear risks have been on the rise for years, and the risk of use of a nuclear weapon is higher today than at any time since the Cuban Missile Crisis. Reducing these risks will require U.S. leadership and renewed commitment to diplomacy and engagement, bold and creative policy choices, and unwavering focus.

The Biden administration took office in January 2021 faced with daunting challenges, domestic and foreign. Although the agenda is crowded, avoiding the cataclysmic risk of nuclear weapons use must be a top priority. The administration’s review of U.S. nuclear policies and posture is taking place against the backdrop of increasing tensions among nuclear-armed states. In addition, the arms control framework that has been integral to managing nuclear competition for decades has eroded, and new technologies and evolving threats add complexity to the challenge of rebuilding it.

The essays in this report reflect the need for a multifaceted response, including (a) changes to U.S. nuclear policies and posture to reduce the role of nuclear weapons in U.S. security policy; (b) renewed engagement with Russia on strategic issues; (c) a deeper foundation of dialogue on nuclear issues with China; and (d) a recommitment to seeking multilateral solutions to strengthen the global non-proliferation regime and reduce nuclear risks. Also necessary is a renewed foundation of trust and cooperation with the invaluable network of U.S. allies and partners in Europe and the Asia-Pacific region, which is fundamental to U.S. national security and serves as a force multiplier for U.S. leadership and interests around the world.

It is crucial to build and sustain domestic support for nuclear security policies that will keep Americans safe. The administration and Congress should establish a new bipartisan liaison group—comprising House and Senate leaders and committee chairs working with senior administration officials—focused on Russia policy, nuclear risks, and NATO. Such a group would facilitate regular communication and greater coherence between the executive and legislative branches and help rebuild consensus in support of engagement and arms control as essential tools in advancing U.S. national security.

The Biden administration should also work to establish policies and processes to put guardrails around the president’s “sole authority” to order the use of nuclear weapons to ensure that any such decision would be deliberative and based on appropriate planning and consultation, including with leaders in Congress. Implementation would be dependent on the particular circumstances that are causing consideration of nuclear use. These policies would improve confidence in how the U.S. government makes critically important decisions and policies related to nuclear use.

The essays in this report recommend additional steps President Biden and his team could take to adapt U.S. nuclear policy and posture to reduce the risk of use of nuclear weapons.

These steps include:

It also is imperative that the United States and Russia reengage to strengthen strategic stability and further reduce both countries’ nuclear arsenals, while continuing to hold Moscow accountable for its violations of international law. As the two countries with the largest nuclear arsenals in the world, both have an obligation—despite their differences—to work to reduce the numbers of these weapons and the risks that they will ever be used. The extension of the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) was an essential first step, and Washington and Moscow must build on that agreement to make further reductions and to address growing challenges to strategic stability.

Recommendations include the following:

While the next round of arms reductions should remain a bilateral U.S.-Russia process, the Biden administration must simultaneously engage China on strategic issues, taking into account the broader regional context. Growing tensions in the U.S.-China relationship, particularly against a backdrop of China’s continued expansion and modernization of its nuclear capabilities, are increasing the risk of conflict and possible escalation to the use of nuclear weapons in the Asia-Pacific.

Formal arms control agreements between the United States and China (or trilateral agreements among the United States, China, and Russia) are unlikely in the near term. Nonetheless, the United States and China should work to develop and sustain a regular dialogue on strategic issues, with a focus on (a) reducing the risk of use of nuclear weapons; (b) constraining the potential for an arms race; and (c) establishing a foundation of engagement that could lead to transparency and confidence-building measures and, over the longer term, potential arms control agreements. These issues cannot be isolated from the broader regional context of the threat posed by North Korea’s nuclear and missile programs and U.S. security commitments to its allies in Asia.

Steps explored in this report include:

Lastly, the Biden administration should restore U.S. leadership of multilateral efforts to reduce nuclear risks. The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) remains the cornerstone of the global non-proliferation regime, and the United States should work with all parties—and in particular through the P5 process—to strengthen the treaty and advance multilateral non-proliferation and disarmament efforts. The United States should work with the rest of the P5 to affirm their commitment to preventing the use of nuclear weapons; expand and deepen dialogue on nuclear issues, including doctrine, risk reduction, and strategic stability; increase transparency on total warheads stockpiles; reaffirm and uphold moratoria on nuclear testing; and declare a moratorium on the production of fissile material for use in nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices.

In today’s world, it is understood that the United States will continue to possess and deploy nuclear weapons for its security and that of allies and partners for as long as is necessary. At the same time, for decades—dating back to the darkest days of the Cold War—the United States has worked to steadily reduce the role and number of these weapons in its security policy. The Biden administration has an opportunity and a responsibility to build on that important legacy, recommitting to the ultimate goal of a world without nuclear weapons and working to make that goal a reality

Chapter 2

By Steve Andreasen

Today, U.S. and Russian ballistic missiles armed with nuclear warheads deployed on prompt launch can be fired and hit their targets within minutes. Once fired, a nuclear ballistic missile cannot be recalled before it reaches its target. Leaders may have only minutes between warning of an attack and nuclear detonations on their territory aimed at eliminating their capacity to respond. This puts enormous pressure on leaders to maintain “launch on warning/launch under attack” options, which—when mutual tensions persist or in a crisis—increases the risk that a decision to use nuclear weapons will be made in haste after a false warning and multiplies the risk of an accidental, mistaken, or unauthorized launch, where millions could be killed in minutes.

Creating robust and accepted methods to increase decision time for leaders, especially during heightened tensions and extreme situations when leaders fear they may be under threat of attack, could be a goal that links both near- and long- term steps for reducing the risk of nuclear use.

Increasing decision time for leaders as an organizing principle has the potential to drive government policy in a number of related security baskets involving nuclear-armed states. It is central to the U.S.-Russia relationship, but also central in the NATO-Russia context and in Washington’s relations with other countries (e.g., China). It also can be used to engage other states with nuclear weapons (e.g., India, Pakistan). There are at least five steps that can and should be proposed now by the Biden administration to increase leadership decision time, working with Russia and other nations:

One of history’s lessons is how quickly nations can move from peace to horrific conflict. In the aftermath, many have looked back and wondered how it could have happened and how it happened so quickly. A new strategy for reducing the risk of nuclear use by increasing decision time for leaders can reduce the chances of conflict and catastrophe.

Chapter 3

By Steve Andreasen

Nuclear declaratory policy encompasses public statements by leaders and governments articulating the circumstances under which nuclear weapons might be used. Declaratory policy communicates to other governments and the public both at home and abroad the role of nuclear weapons in a nation’s security policy, and it is tied to the acquisition and posture of a nation’s nuclear forces.

Since the first and only use of nuclear weapons in wartime by the United States, U.S. leaders have maintained a policy of strategic ambiguity with respect to the future use of nuclear weapons, refusing to rule out nuclear first use.

In its 2010 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR),7 the Obama administration stated that “the fundamental role of U.S. nuclear weapons, which will continue as long as nuclear weapons exist, is to deter nuclear attack on the United States, our allies, and partners.” The administration committed to “continue to strengthen conventional capabilities and reduce the role of nuclear weapons in deterring non-nuclear attacks, with the objective of making deterrence of a nuclear attack on the United States or our allies and partners the sole purpose of U.S. nuclear weapons.” Although the Obama administration never formally adopted “sole purpose,” then-Vice President Biden in early 2017 stated that he and President Obama believed that it should be U.S. policy.8

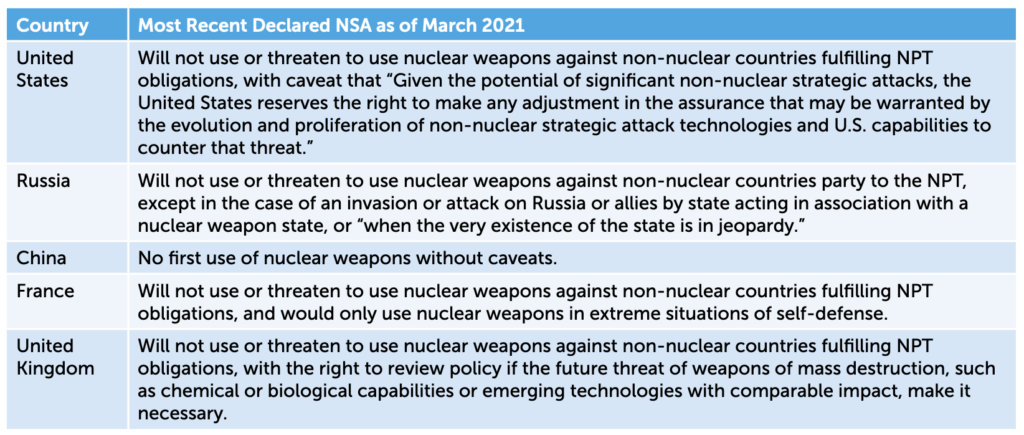

Also in the 2010 NPR, the Obama administration stated, “the United States is now prepared to strengthen its long-standing ‘negative security assurance’ by declaring that the United States will not use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear weapon states that are party to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and in compliance with their nuclear non-proliferation obligations.” In making this “strengthened” assurance, the administration also noted that, “Given the catastrophic potential of biological weapons and the rapid pace of bio-technology development, the United States reserves the right to make any adjustment in the assurance that may be warranted by the evolution and proliferation of the biological weapons threat and U.S. capacities to counter that threat.”

The 2018 NPR9 states that a policy of no first use “is not justified today” in light of the contemporary threat environment, underscoring that, “It remains the policy of the United States to retain some ambiguity regarding the precise circumstances that might lead to a U.S. nuclear response.” The Trump NPR is consistent with the administration’s 2017 National Security Strategy,10 which stated that America’s nuclear arsenal is now “essential” to preventing not just a nuclear attack but also “non-nuclear strategic attacks, and large- scale conventional aggression.” The 2018 NPR, by underscoring the role of nuclear weapons in deterring significant non-nuclear strategic attacks, explicitly rejects sole purpose. While it repeats the Obama-era negative security assurance (NSA), it broadens the exception to that policy, noting, “Given the potential of significant non-nuclear strategic attacks, the United States reserves the right to make any adjustment in the assurance that may be warranted by the evolution and proliferation of non-nuclear strategic attack technologies and U.S. capabilities to counter that threat.”

In January 2017—one week before leaving office—then-Vice President Biden stated:

“Given our non-nuclear capabilities and the nature of today’s threats—it’s hard to envision a plausible scenario in which the first use of nuclear weapons by the United States would be necessary. Or make sense. President Obama and I are confident we can deter—and defend ourselves and our Allies against—non-nuclear threats through other means. The next administration will put forward its own policies. But, seven years after the Nuclear Posture Review charge—the President and I strongly believe we have made enough progress that deterring—and if necessary, retaliating against—a nuclear attack should be the sole purpose of the U.S. nuclear arsenal.”

More recently, in a March/April 2020 essay in Foreign Affairs,11 then-presidential candidate Biden underlined his commitment to sole purpose (reiterated in the 2020 Democratic Party Platform):

“As I said in 2017, I believe that the sole purpose of the U.S. nuclear arsenal should be deterring—and, if necessary, retaliating against—a nuclear attack. As president, I will work to put that belief into practice, in consultation with the U.S. military and U.S. allies.”

Russia’s 2014 military doctrine12 states that it would consider the use of nuclear weapons against any country in extreme self-defense situations:

“The Russian Federation shall reserve the right to use nuclear weapons in response to the use of nuclear and other types of weapons of mass destruction against it and/or its allies, as well as in the event of aggression against the Russian Federation with the use of conventional weapons when the very existence of the state is in jeopardy.”

Most recently, in early June 2020, President Putin signed an official Russian policy paper, titled “Basic Principles of State Policy of the Russian Federation on Nuclear Deterrence,”13 spelling out the principles of Moscow’s nuclear deterrence strategy. The paper repeats the formula quoted above from the 2014 Russian military doctrine, making clear that Russia “considers nuclear weapons exclusively as a means of deterrence, their use being an extreme and compelled measure.”

The paper also states that “in the event of a military conflict, this Policy provides for the prevention of an escalation of military actions and their termination on conditions that are acceptable for the Russian Federation and/or its allies.” This may be a reference to general nuclear capabilities and readiness, rather than an explicit endorsement of early nuclear use or “escalate to de-escalate.”

The paper also makes clear that deployment of nuclear weapons delivery systems, ballistic missile defenses, INF systems (nuclear or conventional), and other advanced weapons in the territory of non-nuclear weapon states that consider Russia as a potential adversary would make them targets of Russian nuclear deterrence.

Finally, in addition to responding to reliable data on a launch of ballistic missiles or the use of nuclear weapons against Russia and/or its allies, the document provides for the possible use of nuclear weapons in response to an attack against the critical national infrastructure that is responsible for controlling and employing nuclear weapons (which many experts have suggested could include cyberattacks that can disable nuclear command-and-control systems).

Alone among the P5, China states that it maintains a “no first use” policy of nuclear weapons with no exceptions. Originally declared in 1964, this pledge has been reaffirmed by Chinese officials on numerous occasions. China has also shown interest in a universal, legally binding P5 negative security assurance toward non-nuclear weapon states.

Neither France nor the United Kingdom has adopted “sole purpose” or “no first use” policies.

In its 2017 Defense and National Security Strategic Review,14 France stated that the “use of nuclear weapons would be conceivable only in extreme circumstances of legitimate self-defense.” In February 2020, French President Macron, noting that the fundamental purpose of France’s nuclear strategy is to prevent war and that French nuclear forces “strengthen the security of Europe through their very existence,” reaffirmed that “France will never engage into a nuclear battle or any forms of graduated response,” but “should there be any misunderstanding about France’s determination to protect its vital interests, a unique and one-time-only nuclear warning could be issued to the aggressor State to clearly demonstrate that the nature of the conflict has changed to re-establish deterrence.”15

In 2015, the United Kingdom stated that “We would use our nuclear weapons only in extreme circumstances of self-defence, including the defence of our NATO Allies. While our resolve and capability to do so if necessary is beyond doubt, we will remain ambiguous about precisely when, how and at what scale we would contemplate their use, in order not to simplify the calculations of any potential aggressor.”16 In 2021, the United Kingdom repeated almost verbatim this language in the “Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy,” stating that “We would consider using our nuclear weapons only in extreme circumstances of self defence, including defence of our NATO Allies . . . we will remain deliberately ambiguous about precisely when, how and at what scale we would contemplate use of nuclear weapons.”17

Both France and the United Kingdom also have adopted NSAs with respect to non-nuclear countries—the French with no caveats and the United Kingdom (in 2021) with caveats relating to chemical or biological capabilities, or emerging technologies with comparable impact (i.e., the United Kingdom leaves open the option to use nuclear weapons in response to chemical or biological attacks or emerging technologies with comparable impact).18

As the Biden administration reviews its nuclear policy and posture, the likely point of departure will be a review of Trump and Obama administration policies and President Biden’s previously stated views on sole purpose, both as vice president and as a candidate for president.

Although President Biden has clearly and publicly stated his position, moving U.S. nuclear allies Britain and France to follow and other U.S. allies in NATO and the Asia-Pacific to support a change in U.S. declaratory policy will be challenging. Although U.S. and NATO defense budgets are unlikely to escape the COVID-19 pandemic without significant programmatic adjustments—including in missile defense and nuclear capabilities—the issue of declaratory policy may be insulated from a NATO defense review. The absence of substantial progress on Ukraine and other political and security issues relating to Russia may create resistance to changing declaratory policy, despite the slightly improved atmosphere for progress on nuclear threat reduction following the extension of New START. Such resistance to a fundamental change of NATO nuclear policy likely will come from many NATO member states.19 Given the worsening political and security dynamic with China, there may be similar reservations among Asian allies to changes in U.S. declaratory policy. According to news accounts, both Japan and South Korea expressed concern about reports that the Obama administration was considering adopting a “no first use” policy in 2016, and the Biden administration is likely to encounter similar resistance to the somewhat different idea of a sole purpose declaration.

Given the potential for resistance, a strategy for moving toward sole purpose declaratory policy will have to clearly lay out the rationale and benefits, while reassuring U.S. allies about the enduring and reliable U.S. commitment to their security.

A new policy narrative—A change in declaratory policy, alone or along with other steps, would need to make clear that reducing the role of nuclear weapons in national security strategy is an urgent priority for the United States and would set a solid foundation for a new direction in U.S. nuclear policy. Importantly, it also would provide a basis for a new process of engagement with Russia and China, with the goal of encouraging and adopting safer policies on nuclear use. Announcing that the sole purpose of U.S. nuclear weapons is to deter nuclear attacks on the United States and its allies and partners—combined with restoring the Obama-era negative security assurance (i.e., the United States “will not use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear weapon states that are party to the NPT and in compliance with their nuclear non- proliferation obligations”)—would clearly signal a policy course change and renewed U.S. global leadership toward reduced reliance on nuclear weapons.

Advancing a new policy—An initiative to move toward a sole purpose policy will need to combine U.S. leadership with deft diplomacy involving U.S. allies in both Europe and Asia, as well as Russia and China. Such an initiative could include a “declaratory policy challenge” to other nuclear weapon states and involve the following three steps:

Flexible implementation—In implementing this approach, a sole purpose declaration could be adopted unilaterally by the United States after consultations with allies, including on reassurance measures. Or, it could be coordinated with other nuclear weapon states. Coordinated unilateral or joint sole purpose statements could be implemented in stages (such as, United States-United Kingdom, United States-China, etc.) as a means of demonstrating progress and incentivizing other countries to act.

P5 Negative Security Assurances (NSAs) at a Glance

Chapter 4

By Lynn Rusten

The United States and Russia must renew and deepen strategic stability dialogue to address the increasingly complex array of capabilities and technologies that could exacerbate military competition and raise the risk of nuclear use. This array includes not only nuclear capabilities but also dual-capable delivery vehicles and hypersonic technologies, conventional prompt-strike systems, missile defense and the offense-defense relationship, cyber capabilities, and military activities in outer space.

Reinvigorated dialogue should lead to new agreements, understandings, and practices to tamp down dangerous competition and enhance mutual security. This cannot be accomplished in a single treaty or agreement but will require comprehensive dialogue on strategic stability that addresses issues in different baskets in parallel. The United States and Russia must change the tone and direction of the bilateral nuclear relationship to signal a renewed commitment to reducing the role and number of nuclear weapons, ensuring a healthy nuclear non-proliferation regime, and reducing the risks of nuclear use bilaterally and globally.

The deterioration in relations with Russia, absence of meaningful dialogue on avoiding crises and maintaining stability, erosion of arms control agreements, and the advance of new technologies have dramatically increased the risk of conflict and of unintended escalation to the use of a nuclear weapon. As the two countries with more than 90 percent of the world’s nuclear weapons, the United States and Russia have a mutual obligation to manage and restrain their military competition and reduce the potential for a nuclear exchange.

Despite significant ongoing tensions, it is essential to build on the long history—dating back to the Cold War—of bilateral dialogue and agreements to reduce nuclear risks. For 50 years, the United States and Russia have judged it to be in their mutual interest to adopt legally binding verifiable treaties to limit and reduce their strategic nuclear forces. These agreements—from SALT I in 1969 to the New START Treaty today—put bounds on their competition in the most destructive nuclear forces, provide predictability, and help reduce the risk of nuclear war. These agreements have contained essential provisions for verification, including intrusive on-site inspections, to provide confidence that any militarily significant cheating would not go undetected. While some believe that the era of such legally binding arms control treaties is over, I and others believe it is still both preferable and possible to negotiate and ratify legally binding verifiable agreements to limit and reduce U.S. and Russian nuclear forces, and, eventually, forces of other nuclear powers too.

Given today’s escalating risks, it is essential to renew and deepen discussions to address the increasingly complex array of capabilities and technologies being pursued by each country that could exacerbate military competition and raise the risk of nuclear use by accident or blunder. Renewed dialogue should address nuclear capabilities as well as dual-capable delivery vehicles and hypersonic technologies, conventional prompt-strike systems, missile defense and the offense-defense relationship, cyber capabilities, and military activities in outer space. These topics must be included in a reinvigorated U.S.-Russia dialogue on strategic stability that ideally should lead to new agreements, understandings, and practices to tamp down dangerous competition and enhance mutual security. Such disparate challenges cannot all be addressed in a single treaty or agreement, but because they are interrelated—and likely to become more so over time—a comprehensive dialogue on strategic stability must begin to identify and chart a course toward addressing many of these key factors.

Since the New START Treaty was negotiated in 2010, the United States and Russia have identified issues and concerns they believe need to be addressed in future agreements. The United States points to Russia’s numerical advantage in non-strategic nuclear weapons (NSNW) and its pursuit of new strategic-range nuclear delivery vehicles, some of which (e.g., the Poseidon nuclear-powered, nuclear-tipped torpedo and the Burevestnik nuclear-powered, nuclear-armed subsonic cruise missile) would not, if they are deployed, meet the definition of a “strategic offensive arm” under New START. In the context of the demise of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, the United States has expressed concerns about Russia’s nuclear-capable intermediate-range land-based delivery systems. Russia, meanwhile, has for years stated that for it to consider reductions below the levels in New START, other factors affecting strategic stability should be taken into account, including missile defense, conventional prompt-strike capabilities, and militarization of space. Russia, and more recently the United States under the Trump administration, has at times argued that future reductions will require bringing other nuclear powers into the arms control process. There also is growing focus on both sides on hypersonic capabilities and cyber risks to nuclear command-and-control systems.

To maintain mutual restraints and verification and achieve further reductions in U.S. and Russian nuclear forces in the future, it will be necessary to address a broader range of factors and military capabilities than has been the case to date. This is unlikely to be accomplished in one comprehensive agreement, but more likely by agreeing to discuss the various issues in several different baskets in parallel. Any ensuing agreements likely will take different forms and proceed on different timelines.

The need for flexible approaches and forms of agreement in addition to treaties could result, for instance, in unilateral or reciprocal actions and commitments, norms or rules of the road, or transparency measures. In addition, because of the pace of technological change, it may be preferable for the time frame of agreements, whatever form they may take, to be more limited—perhaps five or 10 years in some cases—rather than the longer or unlimited duration of some previous agreements. To the extent possible, agreements should include mechanisms for updating to account for new technologies and changed circumstances.

As the countries with the largest nuclear arsenals by far, the United States and Russia should continue addressing many of these issues on a bilateral basis. It may be possible, however, to include China and other nuclear powers in discussions and potentially agreements pertaining to some of these issue baskets, such as those addressing new technologies, either simultaneously or after the United States and Russia have made some progress.

Even before any specific new measures or agreements are reached, there is an urgent need for the United States and Russia to change the tone and direction of the bilateral nuclear relationship to signal a renewed commitment to reducing the role and number of nuclear weapons, ensuring a healthy nuclear non- proliferation regime, and reducing the risks of nuclear use bilaterally and globally. The agreement in February 2021 to extend the New START Treaty for five years was a welcome first step in that direction.

The New START Treaty, now extended to February 5, 2026, is the starting point and foundation for future arms control and other strategic stability measures with Russia. The treaty limits the number of U.S. and Russian deployed strategic nuclear warheads to 1,550 and their deployed delivery vehicles (referred to as “strategic offensive arms”) to 700. It provides for robust verification, including extensive and regular exchanges of notifications regarding the status and location of strategic offensive arms, as well as 18 on-site inspections annually in each country.

By agreeing with Russia to extend the treaty—which otherwise would have expired on February 5, 2021— the United States ensured that Russia’s new Avangard hypersonic delivery vehicles deployed on ICBMs and the Sarmat heavy ICBMs will be subject to the treaty when they are deployed. Two other novel long- range nuclear systems Russia is pursuing that do not fall under the definitions of the treaty—the Poseidon nuclear-powered, nuclear-tipped torpedo and the Burevestnik nuclear-powered, nuclear-armed subsonic cruise missile—are not likely to be deployed, and certainly not in militarily significant numbers, during the life span of New START. And while New START does not limit Russian (or U.S.) NSNW, the treaty’s limits on strategic weapons and its verification provisions provide a critical foundation for the extremely difficult endeavor of negotiating an agreement with Russia to cover classes of weapons beyond what is included in New START.

For the purposes of this paper, the term “nuclear arms control” is used flexibly and is meant to encompass legally binding treaties and agreements and other forms of agreement through which the United States and Russia might reduce nuclear risks through mutually agreed actions or commitments. The extension of New START ensures continued limits and verification on the most destructive class of deployed nuclear weapons in the U.S. and Russian arsenals while the two countries begin to scope out and negotiate additional agreements and measures that can complement and endure beyond New START.

This paper does not address all the issues in the bilateral strategic stability basket. It focuses primarily on further nuclear reductions and a potential successor regime to New START that could include hypersonic, novel, and conventional prompt-strike capabilities; a ban on INF-range systems; and transparency and limits on non-strategic and non-deployed nuclear warheads. (Other important issues related to strategic stability, including the offense-defense relationship, are discussed in separate papers.)

The key recommendations for future arms control steps by the United States, discussed in greater detail below, include:

The United States should announce its intention to reduce its deployed strategic warheads to no more than 1,400 (fewer than the treaty’s ceiling of 1,550) by the end of 2021 and invite Russia to take a reciprocal step. This would send an unmistakable signal of the U.S. commitment to build on the foundation of New START and provide an invitation to Russia to join in recommitting to constructive engagement on nuclear arms control and reducing nuclear risks. By the same token, it is a modest enough step that it would not adversely affect U.S. national security even if Russia does not reciprocate since New START’s binding limits and verification remain in place. (For the past few years, both the United States and Russia have maintained deployed strategic nuclear forces at levels below the New START limits.) Finally, it would be a welcome and reassuring step in the eyes of the international community as nations prepare to participate in the 10th Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) Review Conference and look to the nuclear weapons states—first and foremost the United States and Russia—to demonstrate their continued commitment to the disarmament process.

Agree Not to Base S. or Russian Land-Based Intermediate and Shorter-Range Ballistic and Cruise Missiles in Europe (West of the Urals)

The United States and Russia should begin now to negotiate a new treaty to supersede New START before it expires in 2026. This successor agreement should retain limits and verification on the ICBMs, submarine- launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs), and heavy bombers covered by New START and cover new strategic systems being pursued by both sides. This should include limiting or, in some cases, banning new or novel kinds of strategic-range nuclear delivery systems—such as Russia’s Poseidon (a nuclear-powered, nuclear- tipped torpedo) and Burevestnik (a nuclear-powered, nuclear-armed subsonic cruise missile)—that do not meet New START’s definition of a “strategic offensive arm,” as well as other strategic-range systems, including hypersonic vehicles, whether or not they are deployed with nuclear weapons. The result would be that all so-called strategic-range “conventional prompt global strike systems” would be included in the treaty’s limits.

New START and all previous strategic nuclear arms control treaties with Russia have limited and counted all warheads (or reentry vehicles) attributed to ICBMs and SLBMs as nuclear warheads, regardless of whether they actually are nuclear. Applying this counting rule to all strategic-range delivery systems that are subject to a new agreement would help to address the concern that even conventionally armed, strategic-range, fast-flying, highly accurate systems—such as ballistic or cruise missiles or new hypersonic vehicles—have strategic effect and should be limited because they put at risk the nuclear forces and command-and-control and warning systems of the other side.20

The next treaty should employ more accurate counting rules for nuclear warheads attributed to heavy bombers so that the overall numerical limit on nuclear warheads better reflects the actual nuclear capability of each side. While New START precisely counts the warheads deployed on ICBMs and SLBMs, it uses an attribution rule for heavy bombers such that each bomber counts as having just one nuclear warhead. That is far from realistic because U.S. and Russian bombers can carry up to 12–16 nuclear bombs or cruise missiles.21 Thus, even if the aggregate numerical limit on warheads in a new treaty is not significantly lower than that in New START, adopting more accurate counting rules would lead to a reduction in the actual numbers of warheads and ensure a more meaningful representation of the limit that is being placed on each side’s nuclear delivery capacity.

This is particularly important given that the United States and Russia each are developing new air-launched, long-range nuclear cruise missiles and may pursue long-range, air-delivered hypersonic vehicles in the future. There are significant concerns that such capabilities will be destabilizing because they could pose a first-strike threat to certain key command-and-control facilities. Counting them accurately under an overall warhead limit (or banning them entirely) will be a means of imposing some restraint on these capabilities.

The limits of the next treaty should result in reductions in strategic nuclear capability below the levels permitted under New START. However, including additional kinds of delivery systems under those limits (including potentially strategic-range conventional delivery systems) and adopting more accurate counting rules for warheads attributed to heavy bombers make it difficult at this stage to make a precise recommendation for the limits of the next treaty. It would be an “apples to oranges” comparison with the New START limits. The point would be to more completely include and limit the actual strategic forces on each side and to ensure the numerical reduction of those forces and particularly of deployed strategic nuclear warheads. In addition, robust verification measures will be an essential element of the next agreement, just as they were with New START and previous agreements.

With the priority of reducing the risk of nuclear use, particularly in this age of new technologies including cyber and hypersonics, arms control agreements should be used to encourage each side to adopt more stabilizing nuclear force postures in addition to reducing and regulating the number of nuclear weapons and delivery vehicles. Previous strategic arms control treaties have included provisions intended to encourage each side to adopt more stabilizing force postures. This was the rationale, for instance, behind the original START Treaty’s ban on heavy ICBMs with multiple independently-targeted re-entry vehicles (MIRVs). By the time New START was negotiated, however, each side placed higher priority on preserving its own flexibility than on imposing force structure constraints on the other side. It is time to revisit this trade-off for the next agreement. A meaningful dialogue with Russia regarding how each perceives the impact on strategic stability of particular types of weapons systems would help identify areas where restraint could be mutually beneficial. This can be accomplished by symmetrical constraints, as well as through asymmetrical constraints that reflect trade-offs according to each side’s security concerns, force structures, and preferences regarding how to distribute the permitted elements of its nuclear force posture.

For example, land-based ICBMs, particularly those in fixed silos, are uniquely vulnerable to a possible first strike and create extreme pressure on leaders to “use them or lose them” in a crisis or in the event an incoming attack is detected. This dynamic is exacerbated when it comes to MIRVed ICBMs given that they are “lucrative” targets with more warheads at risk in the event of a first strike. With the goal of improving stability and increasing decision time in a crisis, a new treaty could ban all silo-based ICBMs or, at a minimum, all MIRVed silo-based ICBMs. Because Russia relies more on its land leg than does the United States, Russia likely would seek to retain at least its mobile ICBM force. Recognizing this, a new agreement could require deMIRVing of all ICBMs, including mobiles, or at least limit the number of warheads permitted on mobile ICBMs to, for instance, no more than three. This would make mobile ICBMs less attractive targets and thus reduce the value in trying to locate and take them out in a crisis.

For other systems perceived as particularly destabilizing, the United States should seek to avert their deployment and ban them in the next agreement. This could include the new Russian Poseidon and Burevestnik systems—high-risk, doomsday systems prone to catastrophic accident or miscalculation. Such a ban would be similar to some of the prohibitions in the original START Treaty on deploying strategic nuclear systems undersea or using other exotic basing and delivery modes. Similarly, strategic-range hypersonic vehicles could be banned or permitted only for deployment on ICBMs. Russia may have its own list of concerns about U.S. systems under development. Short of bans, there could be sublimits on certain systems such as hypersonic weapons or air-launched cruise missiles within the overall treaty ceilings.

With the termination of the INF Treaty in August 2019 following the U.S. determination (shared by the Obama and Trump administrations but denied by Russia) that Russia violated the treaty by deploying land-based intermediate-range (nuclear capable) cruise missiles (the 9M729) that exceeded the range permitted by the INF Treaty, the U.S.-Russian global ban on intermediate- and shorter-range (500–5,500 kilometer) land-based ballistic and cruise missiles has been eliminated and there now are no constraints on this class of missiles. After withdrawing from the INF Treaty, the Trump administration began the development of new missiles in this range for possible deployment in Europe or Asia, saying they would be conventionally armed. No allies in Europe or the Asia-Pacific have indicated a willingness to host such missiles. Russia has proposed to the United States and NATO a moratorium on deploying this class of missiles in Europe and, while not conceding that the Russian 9M729 cruise missile is INF-range, has more recently offered to include the 9M729 missile in the moratorium.

The United States and Russia should stop this incipient arms race in its tracks by agreeing not to deploy this class of missiles in Europe west of the Urals and working out the terms of the agreement and appropriate verification and transparency measures to confirm mutual adherence. In doing so, the United States should consult closely with its NATO allies, including on potential transparency measures at the NATO missile defense sites in Romania and Poland to demonstrate to Russia that the United States has not deployed offensive missiles at those sites in place of missile defense interceptors (a concern Russia has raised). While a ban or moratorium would be the most immediate path toward reestablishing a prohibition on INF-range missiles in the Euro-Atlantic region, consideration also could be given to codifying a prohibition on this class of delivery vehicles in the next treaty limiting strategic offensive arms.

Reestablishing the prohibition on deployment in the Euro-Atlantic region is important because INF-range systems are particularly destabilizing owing to their short time of flight and the risk that they could be used to initiate a nuclear exchange or lead to nuclear escalation even if conventionally armed. They also raise concerns about miscalculation because they are dual-capable systems. For these reasons, it is not beneficial to the security of the United States or its NATO allies for this class of systems to remain unregulated. (Nor should the United States pursue deployment of land-based INF-range missiles on the territories of its allies in Asia, as discussed in a separate paper on strategic stability with China.)

Historically, nuclear arms control agreements between the United States and Russia have limited only deployed strategic nuclear warheads and delivery vehicles of strategic- and INF-range. Nuclear warheads intended for deployment on non-strategic delivery systems (NSNW) and other non-deployed nuclear warheads have not yet been subject to arms control agreements. Future arms control agreements should increasingly focus on all types of nuclear warheads to facilitate limits and reductions across the full range of nuclear capability, reduce breakout potential, and enhance verification, particularly as nuclear stockpiles are further reduced.

In the United States there is increasing interest in limiting Russia’s NSNW in future arms control arrangements owing to Russia’s larger stockpile of NSNW and the concerns of NATO allies about Russia’s NSNW near Europe. The Senate resolution of ratification for New START called on the United States to seek negotiations with Russia on NSNW. The Obama administration endeavored to do so, but Russia showed no interest. While the Trump administration in its final months sought to leverage a proposed one-year extension of New START in exchange for Russian agreement to freeze total warhead stockpiles (with details, definitions, and verification to be worked out later), Russia did not agree to that proposal. The main concern with respect to Russia’s NSNW is their availability for use in the European theater on tactical (and now also on INF-range) systems where they can threaten U.S. allies and partners. Given their close proximity—and resulting very short delivery times—to allies’ territory, these systems are viewed as particularly threatening to European allies with potential to be used early in a conflict and lead to escalation to large-scale nuclear exchange. Similarly, U.S. forward-based nuclear weapons in Europe concern Russia because of the short time of flight from Europe to Russian territory. Those European bases where U.S. nuclear weapons are stored would be early targets in a conflict, risking nuclear escalation. Therefore, it would be stabilizing to mitigate these concerns through agreements that could enhance transparency, establish numerical limits, and provide verifiable locational restrictions on where Russian and U.S. NSNW may be stored.

Just as the United States has been concerned with Russia’s numerical advantage in NSNW, which are not deployed on a day-to-day basis, Russia has at times expressed concern about the greater capacity of the United States to “upload” additional nuclear warheads on its strategic delivery systems. One mutually beneficial way of addressing U.S. and NATO concerns about NSNW and Russia’s concerns about a perceived U.S. advantage in non-deployed strategic warheads could be to address in an agreement all non-deployed nuclear warheads, or the total warhead stockpile, of each side.

The next phase of nuclear arms control with Russia should begin to grapple with this challenge. Doing so will be difficult in part because the U.S. and Russian nuclear warhead stockpiles and operational practices are asymmetrical and because there are national security sensitivities related to the design, life cycle, and operational practices pertaining to nuclear warheads. Verification measures, if pursued, will be technically difficult to develop and raise important national security considerations. Moreover, the United States and Russia do not yet have shared objectives in this area, so finding common ground will not be easy. Progress on the U.S. objective of limiting Russian NSNW may require trade-offs across other issues in the strategic stability basket.

Below are two illustrative approaches to consider for increasing transparency and/or limiting non- strategic and non-deployed nuclear warheads. (A third approach regarding locational restrictions on U.S. and Russian NSNW in Europe west of the Urals is discussed in a separate paper.) These approaches are complementary—the two sides could pursue one or more of them and they could be advanced together or sequentially.

at varying levels of detail and specificity, for instance by providing some or all of the following information:

Such declarations could be made as unilateral, reciprocal confidence-building measures, or they could be incorporated into agreements that also include measures for transparency, confirmation, and verification as a first step toward, or in conjunction with, agreed numerical or geographic limits and restrictions.

The ideas suggested in this paper for (a) a potential successor regime to New START that would cover a more comprehensive array of strategic-range nuclear and conventional systems and new technologies; (b) a moratorium on INF-range missiles; and (c) transparency and limits on NSNW and non-deployed nuclear warheads represent an important but incomplete set of proposals to address key factors that are affecting strategic stability between the United States and Russia. Other important issues such as the offense-defense relationship and additional considerations regarding the risks of NSNW in Europe are discussed separately in this volume. Additionally, there are subjects including cyber risks to nuclear command-and-control and warning systems, implications of artificial intelligence, and military activities in space that, while not discussed in detail in this report, are critical issues for inclusion in a wide-ranging and in-depth strategic stability dialogue with Russia.

Chapter 5

By Steve Andreasen

Both the United States and Russia have in their arsenals nuclear warheads intended for use on non-strategic delivery systems. The United States reportedly has approximately 100 non-strategic nuclear weapons (NSNW) stored at NATO bases in Europe and approximately 130 stored in the continental United States,23 while Russia reportedly maintains nearly 2,000 NSNW for use on various delivery platforms throughout its territory.24 These U.S. and Russian weapons are currently not covered by any nuclear arms control treaties or constraints; hence their numbers, storage and deployment locations, alert status, and security are shrouded in uncertainty, which fuels mutual suspicion and could generate concerns in a crisis. The shorter range and vulnerability of their delivery systems raises the specter of early use in a regional crisis and the potential for escalation to large-scale nuclear exchange.

Nuclear weapons have played a key role in the collective defense policy of NATO since 1954 and are seen as the alliance’s ultimate deterrent to aggression. The arsenal committed to NATO includes forward-deployed U.S. NSNW stored in Europe, U.S. strategic nuclear forces that compose the nuclear triad (i.e., land-, sea-, and air-based), and U.K. strategic nuclear weapons deployed at sea. As with most assets committed to NATO, the U.S. and U.K. nuclear forces are nationally owned and are under national command and control. In addition, France’s independent strategic nuclear forces “have a deterrent role of their own” and “contribute to the overall deterrence and security of the Allies.”25

According to published sources, today there are approximately 100 U.S. non- strategic gravity B61 warheads stored at six U.S. nuclear weapon facilities in five NATO countries: Belgium (10–20), Germany (10–20), Italy (40), Netherlands (10–20), and Turkey (20).26 These weapons are for use on U.S. and allied dual- capable aircraft (DCA); the weapons are under U.S. control and may only be used following presidential authorization.27 DCA currently deployed by the United States and NATO host countries include the F-15E Strike Eagle, F-16 Fighting Falcon, and Panavia PA-200 Tornado.

These capabilities and the accompanying supportive force structures, infrastructure, and exercises come under a long-established NATO nuclear consultation, planning, and decision-making framework. Although the United States has a leading role, allied participation and burden-sharing remain central to the concept of NATO collective defense and nuclear deterrence.

As part of a comprehensive plan to upgrade its nuclear forces, the United States has begun the process of modifying the existing B61 nuclear gravity bomb by consolidating all five current variants into a single weapon, the B61-12. Today, some current B61 variants can be delivered only by tactical DCA, whereas others can be delivered only by long-range strategic bombers. The new B61-12 (consisting of two components, the bomb assembly and the guided tail kit assembly that enables the bomb to be employed with greater accuracy than current gravity bombs) will be deliverable by both, increasing the weapon’s flexibility and interoperability but potentially blurring the distinction between tactical and strategic missions. The first production unit of the new B61-12 will occur in fiscal year 2022 and will be completed in 2025.28

Concurrently, the inventories of DCA owned by NATO countries hosting the U.S. B61 are reaching the end of their original service lives. These countries therefore are making (or already have made) decisions regarding replacement aircraft and the investments necessary to retain the DCA mission. The Netherlands, Italy, and Belgium are planning to buy nuclear-capable F35-A Joint Strike Fighters from the United States, which will begin replacing existing NATO aircraft in 2024 (in 2019, the Trump administration halted delivery of F-35As to Turkey because of its plans to acquire the Russian S-400 air defense system). Germany is expected to extend the service life of its nuclear-capable PA-200 Tornado through the 2020s and purchase F-18 fighter jets to be used in part for the nuclear mission in later years.

Overall, the U.S. Congressional Budget Office estimates that over the 30-year period from 2017 to 2046, tactical nuclear forces will cost the United States $25 billion, or an average of nearly $1 billion per year.29

Today, Russia’s nuclear arsenal of approximately 4,300 warheads is estimated to include approximately 1,870 so-called non-strategic or tactical nuclear weapons.30 These weapons, as well as ongoing improvements in Russia’s conventional capabilities, often are cited as a core justification for retaining NATO’s current nuclear posture.

Russia is currently modernizing all aspects of its nuclear arsenal. As in its strategic weapons modernization program, Russia appears to be phasing out older Soviet-era weapons in favor of a smaller force of new systems. According to one comprehensive assessment of Russian nuclear forces, in the longer term, “the emergence of more advanced conventional weapons could potentially result in reduction or retirement of some existing nonstrategic nuclear weapons.”31

The Russian Navy is fielding a new class of nuclear attack submarines, and a new dual-capable cruise missile has been demonstrated in ship- and submarine-launched strikes in Syria. The Russian Air Force also is fielding a new air-launched nuclear cruise missile. Another new system, the ground-launched 9M729 cruise missile, is the subject of U.S. accusations that Russia violated the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty by flight-testing and deploying a new ground-launched cruise missile in excess of the range limits on such capabilities.32 The missile was reportedly deployed in early 2017.33

China has an estimated 320 nuclear warheads and, according to the head of the U.S. Strategic Command (Adm. Charles Richard), is undergoing an “unprecedented expansion” of its nuclear and strategic capabilities, driving to be a strategic peer by the end of the decade. This drive includes an increasing capability to produce plutonium for weapons with the intent of doubling China’s stockpile, and changes in its nuclear posture to ensure a credible nuclear triad. According to Richard, “China is capable of executing any plausible nuclear employment strategy regionally now and will soon be able to do so at intercontinental ranges”—a factor in both U.S. and Russian nuclear planning and decision making (though both the United States and Russia still possess vastly larger arsenals, at around 4,000 warheads each, deployed and stockpiled).34

Although the United States and NATO have undertaken considerable efforts to improve the physical security of nuclear weapons stored in Europe, it should be assumed that those weapons remain potential targets for terrorist attacks. Storing nuclear weapons at locations throughout Europe to reassure some allies or to use as leverage in a future arms control deal with Russia, therefore, comes with the increasing risk of vulnerability to an evolving and deadlier terrorist threat. (In contrast, nuclear weapons in the continental United States are secured in central storage facilities that are easier to protect than dispersed underground vaults inside aircraft shelters across multiple bases in Europe.) Russia’s nuclear weapons may be similarly vulnerable, with an estimated 1,850 non-strategic nuclear weapons reportedly kept in storage facilities throughout the country, some located near operational bases.

The political and security context for any initiative to change NATO’s nuclear posture in 2021—including consolidating forward-deployed nuclear weapons from NATO/Europe to the United States—will remain challenging.

Public opposition to nuclear weapons in most NATO countries has produced a preference by most governments to avoid public discussion of nuclear weapons policy. The preference for a low profile has been reinforced by the tendency of alliance members to rely on U.S. leadership. The consequence is a reluctance to consider alternative approaches or to fundamentally reassess whether the current nuclear posture still meets contemporary deterrence and defense requirements, as well as the risks and costs associated with sustaining the current posture.

In the absence of substantial progress on Ukraine and other political and security issues relating to Russia, the case that forward-deployed nuclear weapons are more of a security risk than an asset likely will encounter substantial resistance from some NATO member states, in particular those nearer to Russia. In addition, allied unease has been compounded by the decades-long decline in U.S. military personnel and infrastructure in Europe, including most recently the Trump administration’s reductions in funding for the European Defense Initiative and proposed reductions in U.S. troops stationed in Germany. Despite the Biden administration’s recent announcement that it will increase the U.S. military presence in Germany, the uncertainties generated by these actions make “reassurance”—an essential prerequisite for a change in NATO’s nuclear posture—even more difficult. The demise of the INF and Open Skies treaties has accentuated both unease and nuclear uncertainty in the Euro-Atlantic region.

However, recent instability along NATO’s borders—and even within individual NATO countries—also highlights the continued and perhaps growing risks associated with the current posture. The COVID-19 pandemic will continue to inflict severe economic costs on the United States and NATO member states, perhaps for years to come. It is hard to see how U.S. and NATO defense budgets escape this pandemic without significant adjustments. The potential for widespread and perhaps long-standing cuts in U.S. and NATO defense spending will contribute to unease among NATO member states; however, it may also provide an incentive for a review of defense capabilities, including nuclear capabilities, in light of post-pandemic security and economic priorities. Resistance in NATO (and within the U.S. government) to changing NATO’s nuclear status quo could also be reduced if accompanied by an arms control proposal to address Russia’s forward-deployed nuclear weapons. Moreover, there is also the possibility of a change in government in at least one key NATO member state, Germany, where the Green Party (which has enshrined the goal of a nuclear-free Europe into their party platform and calls for a Germany without U.S. nuclear weapons) could emerge as a political power in Germany’s post-September 2021 election government.

Finally, even in the absence of a COVID-19–inspired review, a new U.S. administration will almost certainly conduct a defense policy review that would include nuclear policy and posture, and NATO. Indeed, a new Strategic Concept and/or Deterrence and Defense Policy Review might be a logical follow-on to the NATO secretary general’s “forward-looking reflection process,” which was charged with offering recommendations to reinforce alliance unity, increase political consultation and coordination between allies, and strengthen NATO’s political role. The analysis and recommendations of the Reflection Group were made public in November 2020.35

Allied perceptions regarding threats and responses will never completely overlap in an alliance with 30 member states; however, differences must not lead to alliance stagnation when it comes to reducing the risk of nuclear use.

The rationale for maintaining U.S. and Russian forward-deployed nuclear weapons in Europe indefinitely is dangerously out of date, for both countries and for Europe. Engaging political leaders on both sides of the Atlantic—and substantial dialogue with Russia—will be required to change the status quo to better match today’s realities.

Any near-term initiative to eliminate forward-deployed nuclear weapons must proceed and succeed within the frame of the persistent negative political dynamic between NATO and Russia. Addressing issues related to reducing the risk of nuclear use, sharing nuclear risks and responsibilities, assuring allies, and defining a strategy for engaging Russia are and will remain central. In this context, any reduction in costs associated with the nuclear mission could free up resources for NATO member countries to focus on other urgent tasks, including post-pandemic economic recovery, conventional reassurance, and cyber defense.

As part of a new nuclear and defense policy review in 2021, the United States and NATO should develop a set of commitments to provide a foundation for changing the nuclear status quo. An early focus should be to remove weapons from areas where there is a heightened risk of terrorism or political instability (recognizing how recent events underscore how quickly assumptions about the safety and security of U.S. nuclear weapons stored abroad can change).

Chapter 6

By Steve Andreasen

Since the late 1960s, missile defense has reliably been at the nexus of defense, foreign policy, and arms control for the United States and Russia. In the current state of strategic instability—including the withering of arms control agreements—where an accident or mishap could trigger a catastrophic chain of events, the stakes associated with finding a truly cooperative path forward on missile defense, and more broadly an agreed framework for managing the relationship between strategic defense and offense and reducing nuclear risks, have never been higher. In the absence of such cooperation, the cycle of competition between deployment of missile defenses and advances in offensive capabilities to defeat them will continue to fuel dangerous nuclear competition and pose an obstacle to reaching new agreements to limit and reduce nuclear weapons.

Further progress in improving U.S.-Russia relations and nuclear threat reduction depends in part on developing a cooperative approach to missile defense, beginning with the U.S./NATO and Russia. Unfortunately, the historic track record on U.S./NATO-Russia missile defense cooperation is not promising:

Enter China—A further complication in the offense-defense relationship, in particular as it relates to missile defense, is China. Over the past 20 years, China has consistently objected to U.S. missile defense deployments, in particular U.S. “theater” missile defense deployments in the Asia-Pacific region. Going forward, as the United States seeks to engage China more broadly on regional and global security and stability, including discussions relating to Chinese nuclear forces, the issue of missile defense is likely to play an even greater role.

While legally binding limits on missile defense are almost certainly politically infeasible in the United States at present, progress on improving U.S.-Russia—and to some degree U.S.-China—relations and reducing the risk of nuclear use will require the United States to review this matter with fresh eyes and develop a more cooperative approach to missile defense, one that will address at least some Russian and Chinese concerns about U.S. missile defense capabilities. Practical steps could be agreed to create a positive dynamic for discussions and further boost what will be a continuing effort in the years ahead to deepen cooperation in this area.

In the 2019 Missile Defense Review (MDR),38 missile defense was identified as “an essential component of U.S. national security and defense strategies,” contributing both to deterrence of adversary aggression and the assurance of allies and partners. The program is designed to “counter the expanding missile threats posed by rogue states and revisionist powers to us, our allies, and partners, including ballistic and cruise missiles, and hypersonic vehicles.” Russia and China are explicitly named in the discussion of the evolving threat. North Korea, Iran, Russia, and China (which “can now potentially threaten the United States with about 125 nuclear missiles, some capable of employing multiple warheads”) are identified as current or future threats to the U.S. homeland.

The MDR narrative goes on to state that the United States relies on deterrence to protect against large and technically sophisticated Russian and Chinese threats to the U.S. homeland: the purpose of U.S. missile defense is to “outpace” existing and potential rogue state (i.e., North Korea and Iran) offensive missile capabilities. These efforts “will require” the examination and possibly fielding of advanced technologies, including space-based sensors and boost-phase defense capabilities, and possibly adding capacity and capability to “surge” missile defense. For this reason, the MDR states “the United States will not accept any limitation or constraint on the development or deployment of missile defense capabilities needed to protect the homeland against rogue missile threats.” The MDR also notes that, “As rogue state missile arsenals develop, the space-basing of interceptors may provide the opportunity to engage offensive missiles in their most vulnerable initial boost phase of flight.”

Today, the United States deploys the Ground-based Mid-Course Defense (GMD) system to defend against a limited ICBM attack from “any source.” Forty Ground-Based Interceptors (GBIs) are deployed at Fort Greely, Alaska, and four at Vandenberg Air Force Base, California. Congress appropriated an additional $1.3 billion in FY21 for missile defense above the administration’s Missile Defense Agency (MDA) budget request of $9.13 billion.39 The MDR states that DOD will increase the number of deployed GBIs, including a new GBI interceptor, from 44 to 64 beginning as early as 2023; and the Fort Greely site has the potential for up to an additional 40 interceptors. The MDR also references the possibility of a new GBI interceptor site in the continental United States.

Regional defenses include seven Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) batteries, including one in Guam and one in South Korea. The United States is testing improved variants of both the Aegis SM-3 and SM-6 missiles, for deployment at sea and ashore. An Aegis Ashore site in Romania is operational, armed with the SM-3 interceptor; an Aegis Ashore site in Poland is expected to be operational in 2022. Both Aegis Ashore sites are expected to be equipped with the SM-3 Blk IIA—capable of providing added protection against ICBM threats. The U.S. MDA tested the ship-based SM-3 Blk IIA against an ICBM-class target in November 2020. Patriot Advanced Capability-3 is now deployed with U.S., allied, and partner forces in multiple theaters to defend against short-range ballistic and cruise missiles.

The MDR states that Russia is maintaining and modernizing its anti-ballistic missile (ABM) system deployed to protect Moscow from nuclear attack, including 68 nuclear-armed interceptors, and multiple shorter-range systems throughout Russia. China is described as “aggressively pursuing a wide range of mobile air and missile defense capabilities,” including testing a new mid-course missile defense system.

Perhaps more significant programmatically, both Russia and China are developing and deploying offensive nuclear, cyber, and space capabilities explicitly to defeat U.S. missile defenses. Thus, as has been true historically, improved U.S. missile defense capabilities are fueling the development and deployment of new, more sophisticated offensive capabilities by U.S. competitors and adversaries.

The domestic political and international security context for an initiative to engage on the “offense-defense” relationship and take concrete, specific steps relating to missile defense is fraught with challenges. Threading the political needle at home, and security and diplomatic needle with Russia and China, will be a challenge for any U.S. administration.

To begin, a core tenet of conservative orthodoxy for decades has been support for missile defense, unfettered by the ABM Treaty and any other constraint regimes. Moreover, lawmakers in both political parties support U.S. missile defense programs. Any initiative that appears to open the door to limitations or constraints, in particular legally binding constraints, will be strongly resisted.

Second, the Russian position for some time has been that not just constraints, but “legally binding” constraints, are necessary in the area of missile defense for there to be any additional constraints, including reductions, in U.S. and Russian nuclear forces.

Third, at least in the area of strategic stability and nuclear threat reduction including arms control, any improvement in U.S.-Russia relations and reduction of risk of nuclear use are likely to require the United States to engage on missile defense. A new U.S. administration almost certainly will conduct a defense policy review that would include missile defense, offering an opportunity to revisit the issue; however, domestic opposition, including in Congress, to constraints on missile defense will continue to be a significant factor.

Lastly, although missile defense and the offense-defense relationship in general may be more immediate and central to a review of U.S. policy vis-à-vis Russia, any decisions taken in this context also could significantly impact U.S.-China policy, including with respect to engaging China on regional stability and nuclear forces. At a minimum, a framework for engaging Russia in this area should be conscious of the potential impacts on U.S.-China policy; more proactively, the United States might seek to discuss some of the same issues with China, or even involve China in implementation.

The most realistic frame for engaging on missile defense in a U.S.-Russia context almost certainly includes NATO—in part owing to NATO deployments that concern Russia, but also to enhance trust and cooperation between Washington and Brussels.

Additionally, although the objective would be to develop practical steps that could be taken through politically binding arrangements, a frame that focuses first on specific steps that would not require new legally binding treaties is most realistic from the standpoint of U.S. domestic politics, recognizing that this may not be sufficient for Russia.

If it can be done, this approach could create a positive dynamic for discussions and further boost what will be a continuing effort in the years ahead to deepen cooperation in this area. Such an approach also could inform negotiation of any new legally binding treaties and improve prospects for their approval by legislatures and parliaments.

In this context, there are a number of steps that could ensure that the historic and persistent barriers to a truly cooperative approach to missile defense do not thwart future efforts. Political will and leadership from the most senior levels in Washington and Moscow will be needed to make progress; otherwise, they will get stuck in the usual bureaucratic ruts in both capitals.

Steps could include:

Chapter 7

By James McKeon and Mark Melamed

As the relationship between the United States and China becomes ever more central—and increasingly fraught—there is an urgent need for the two countries to better manage the strategic relationship and avoid blunders or miscalculations that could have potentially catastrophic implications for both countries and for the world at large. The mutual recriminations and attempts to assign blame for the COVID-19 pandemic and related economic downturn, combined with simmering commercial and geopolitical tensions, have produced an even more antagonistic relationship between the two countries, increasing the risk that bilateral tensions could result in a dangerous and unnecessary new Cold War.

The future of the U.S.-China relationship will necessarily require a balance between competition and cooperation—and as tensions rise, it will become ever more important to strengthen the latter where necessary to reduce nuclear risks. However, unlike the U.S.-Russia relationship where there is a long history of engagement on managing nuclear risks and engaging in arms control, the United States and China have almost no tradition of bilateral dialogue or negotiation on strategic issues.

Over the course of multiple presidential administrations, the United States has sought to engage China on nuclear weapons and strategic security issues, mostly without success. The Trump administration’s efforts focused on drawing China into a trilateral U.S.-Russia-China nuclear arms control process, an approach Beijing has rejected repeatedly, citing a major disparity in the size and composition of China’s nuclear arsenal compared to the United States and Russia. For example, in July 2020, Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian stated, “China’s objection to the so-called trilateral arms control negotiations is very clear, and the U.S. knows it very well.”41

For reasons examined more fully later, an approach that prioritizes near-term trilateral arms control is unlikely to succeed. Instead, this paper offers an alternative strategy for engaging China that starts with a recognition that there is no shortcut from the historical absence of even a baseline level of dialogue to full-fledged arms control agreements. Given China’s rising military power and considerable military investment—in its nuclear forces and other strategic capabilities, including conventional and dual-use missiles and hypersonic systems, cyber capabilities, and anti-satellite and other space capabilities—efforts to broaden and deepen bilateral engagement with China are essential. The initial focus of U.S.-China engagement to reduce the risk of nuclear conflict between the two countries should be to develop a foundation of dialogue and mutual understanding, leading to transparency and confidence-building measures, and ultimately, as a longer-term goal, arms limitations and/or reductions.

Managing the strategic relationship between the United States and China, including building and maintaining strategic stability, avoiding crises that could escalate to the use of nuclear weapons, and managing crises that do emerge to ensure they do not escalate to nuclear use, is crucial. Just as it is imperative that the United States and Russia remain engaged on strategic issues, it is critical that the United States and China find ways to reduce the risk of use of nuclear weapons, notwithstanding broader bilateral tensions. The world narrowly survived the U.S.-Soviet nuclear brinksmanship of the Cold War; there is no guarantee it can survive another trip down that path between the United States and China.

With that in mind, engagement on strategic issues between the United States and China should be oriented around three key objectives:

Over the past decade and across administrations of both political parties, the U.S. government increasingly has viewed China as a great power competitor and potential adversary, often in the same vein as Russia. In making its case for trilateral arms control, the Trump administration rightly noted China’s growing economic and military power, Beijing’s considerable investment in modernizing its nuclear forces and increasing the number, types, and survivability of delivery systems, and China’s growing regional and global influence. However, there are a number of reasons that bringing Beijing into traditional, limits-based nuclear arms control is likely to prove infeasible in the near term.

First and foremost, China’s nuclear arsenal is dwarfed by the U.S. and Russian stockpiles, notwithstanding the considerable reductions by Washington and Moscow over several decades. While the precise size of China’s arsenal is unknown, estimates generally center around 350 warheads, according to the Federation of American Scientists (FAS)—considerably fewer than even just the deployed stockpiles of the United States and Russia. At any one time, the United States deploys at least many hundreds of nuclear warheads that can potentially reach China, with low thousands in reserve. By contrast, FAS estimates that China has approximately 150 nuclear missiles that can potentially reach the United States (FAS estimates these 150 warheads could carry approximately 190 total nuclear warheads), and that—of those—about 90 missiles (carrying approximately 130 nuclear warheads) could reach the continental United States.42

Given this disparity, any limits in a trilateral agreement modeled on existing arms control frameworks would either have to be (a) set so high as to be effectively meaningless for China (or, perversely, even incentivize Beijing to build up its arsenal to the limit); (b) set so low as to require massive reductions in the U.S. and Russian stockpiles, which Washington and Moscow are unlikely to agree to; or (c) unequal (i.e., keeping China’s stockpile where it is while allowing Russia and the United States to retain much larger stockpiles), which China would have little or no incentive to support. Perhaps primarily owing to this disparity, in addition to other factors, China has repeatedly made clear that it has no interest or intention at this stage in joining bilateral U.S.-Russia arms control efforts.

There are other impediments to negotiating arms control agreements with China in the near term. While the United States and Russia have built up years of experience with dialogue on nuclear issues, China has been—and remains—hesitant to engage in the kind of discussions and transparency that could lay a similar foundation in the U.S.-China—or U.S.-China-Russia trilateral—relationship. China has no experience with the on-the-ground inspection and intrusive verification regimes that have been an essential feature of most U.S.-Russia arms control agreements. China has traditionally been deeply skeptical of efforts to increase transparency on its nuclear capabilities, likely owing to its significantly smaller arsenal and its official “no first use” policy, which make Beijing especially wary of sharing information that could make China more vulnerable to a disarming first strike in the event of crisis or conflict.