Lynn Rusten

Vice President, Global Nuclear Policy Program

This article originally appeared in USA Today on August 6, 2020.

Seventy-five years ago today, Aug. 6, 1945, the atomic bomb incongruously named “Little Boy” detonated above the Japanese city of Hiroshima, incinerating tens of thousands of people and injuring tens of thousands more. The force of the blast and firestorm from that bomb, and a second one dropped three days later, on Aug. 9, over the city of Nagasaki, were almost beyond comprehension at the time. The true toll of the massive radiation release wouldn’t be felt for years.

Today, the numbers of those who survived to bear witness to that horrific experience are dwindling, and for far too many people, nuclear weapons are an abstraction. Even for those of us who have dedicated our careers to national security and reducing nuclear risks, it’s far too easy to debate the arcana of nuclear policy, forces, deterrence and arms control without reflecting sufficiently on what it would mean for even one “small” nuclear weapon to be used.

The 75th anniversary of the first and only wartime use of nuclear weapons — by the United States against Japan in World War II — is an appropriate time to reflect on the lives lost or forever changed, and the incredible physical, environmental and economic destruction. It reminds us never to lose sight of the staggering human consequences of using nuclear weapons.

Thousands of nuclear warheads

Each year, the Hiroshima Prefecture hosts an international roundtable of experts to discuss ideas for reducing reliance on nuclear weapons and making progress on disarmament. After three decades working on nuclear arms control, I was looking forward to participating and, with my 27-year-old daughter, visiting the city and the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum — a deeply moving experience for everyone I know who has visited. It would have been my first trip to Hiroshima, what should be a required pilgrimage for everyone working on nuclear policy.

Of course, COVID-19 interrupted those plans. The pandemic that has already claimed more than 650,000 lives worldwide serves as a potent reminder that catastrophic events that may seem impossible or improbable are not, and we must do all we can to avert them.

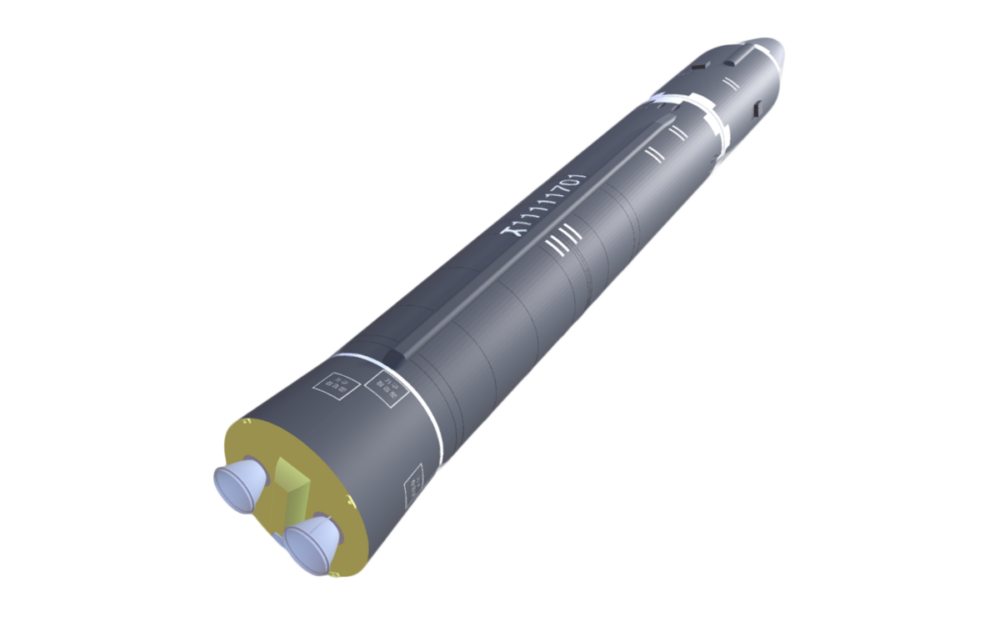

Today, there are still an estimated 13,410 nuclear warheads on the planet, and the risks of nuclear use around the globe are evolving and escalating. Among today’s threats:

Increased tensions and risks following the regrettable decision of the Trump administration to walk away from the 2015 Iran nuclear agreement that was working to keep Iran from getting materials for a nuclear weapon.

The last proliferation guardrail

The most urgent step: Preserve the last guardrail keeping Russian and U.S. nuclear arsenals in check. The 2011 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START), which I helped to negotiate, is set to expire in February 2021. This is the last remaining arms control treaty that limits the number of U.S. and Russian strategic nuclear weapons and provides extensive verification, including 18 on-site inspections each year. Only by acting now to extend New START for five years, as the treaty permits, can we avoid creating an unregulated strategic nuclear environment for the first time in 50 years.

I know from my personal experience that it is a lot harder to develop, negotiate, ratify and implement hard-nosed nuclear reduction agreements than it is to tear them down in search of a mythical “better deal.” Throwing away the constraints we have with nothing to put in their place simply makes no sense.

On his visit to Hiroshima in 2019, Pope Francis said what happened there should be “capable of awakening the consciences of all men and women, especially those who today play a crucial role in the destiny of the nations.” We all have a duty to heed this call to conscience.

Lynn Rusten is vice president of the Global Nuclear Policy Program at the Nuclear Threat Initiative. She previously served as the senior director for arms control and nonproliferation on the White House National Security Council staff. She helped negotiate the 1991 START Treaty and the 2011 New START Treaty.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest on nuclear and biological threats.

A collection of missile tests including the date, time, missile name, launch agency, facility name, and test outcome.

At this critical juncture for action on climate change and energy security, 20 NGOs from around the globe jointly call for the efficient and responsible expansion of nuclear energy and advance six key principles for doing so.

Information and analysis of nuclear weapons disarmament proposals and progress in Belarus