Atomic Pulse

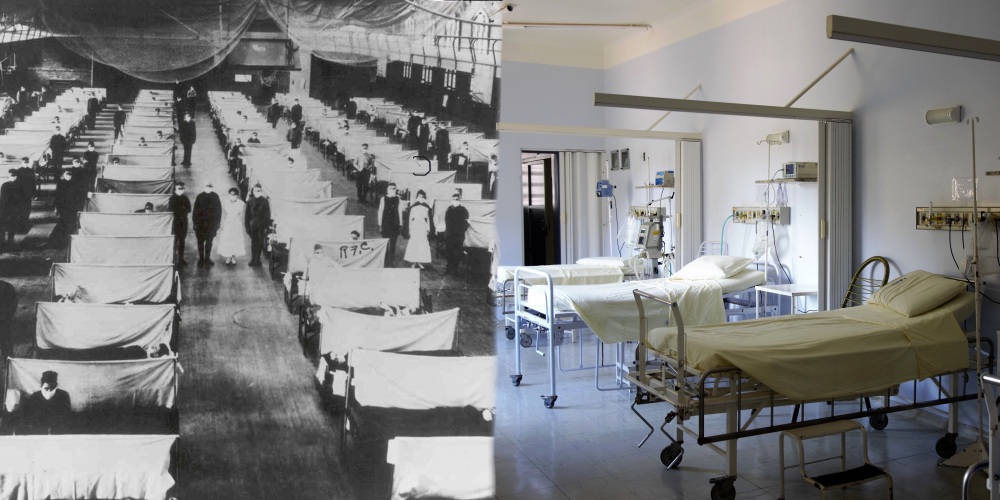

The 1918 Global Flu Pandemic Killed 50 Million People. Could it Happen Again?

This year is the 100th anniversary of the year 500 million people became infected with the flu, resulting in 50 million deaths worldwide. The 1918 Flu Pandemic devastated the world and was exacerbated by close living conditions and massive troop migration during World War I. The absence of effective countermeasures and limited knowledge about disease transmission made responding to the pandemic almost impossible. This month, NTI Communications Manager Caitlyn Collett sat down with Beth Cameron, NTI’s Vice President of Global Biological Policy and Programs, to discuss how the world has changed since 1918 and what should be done globally to prevent a similar pandemic and to reduce global catastrophic biological risks.

Caitlyn Collett: One hundred years ago, 50 million people died in a global flu pandemic. Could a pandemic of that magnitude happen again, and if it could, do you think it would be as bad as it was 100 years ago?

Elizabeth Cameron: Yes, and it’s not a question of whether a pandemic could happen, it’s really a question of being prepared for when it will happen. If a flu pandemic like the 1918 flu were to happen again, it would travel even more quickly around the world because we’re increasingly connected. Additionally, since we still don’t have universal flu vaccine capabilities, in the first several months there wouldn’t be a vaccine against the emerging outbreak.

Collett: So we’re even more at risk in some ways than we were 100 years ago. Do you see a particular existing disease or virus that biosecurity experts should keep an eye on?

Cameron: I think most experts in health security are keeping their eye on new flu viruses that have pandemic potential as they emerge. H7N9, which emerged in 2013, is a flu that experts are definitely keeping an eye on to track potential human-to-human transmissibility.

At NTI, we also worry about the growing ability to create and modify viruses like flu in a laboratory setting, which could lead to the emergence and spread of a new virus or one developed maliciously to evade countermeasures.

In fact, NTI just launched a new effort – the Biosecurity Innovation and Risk Reduction Initiative – to develop novel mechanisms for reducing biological risks associated with advances in technology.

Collett: That’s definitely motivation to get your flu shot. What’s changed since 1918 – both things that increase global catastrophic biological risks and those increase capacity to prevent, detect, and respond?

Cameron: The world is increasingly connected. Travel, trade, increase in urbanization, people living in denser populations, the rise in technology, the ability to create and modify pathogens… all of those things can increase global catastrophic biological risks. The world is better prepared to deal with some disease threats – for example, we now have capabilities to make drugs and vaccines, but it still takes much too long make an effective vaccine or therapeutic for a disease threat – like a new pandemic strain of flu – that the world has never seen. We also know that most countries in the world are not prepared to prevent, detect, and respond to a disease outbreak of this magnitude. The good news is we have new tools to understand exactly what the gaps are through the World Health Organization (WHO) Joint External Evaluation. Some countries have already conducted these evaluations, but unfortunately not all countries have taken the time to do so. Furthermore, most that have conducted evaluations identified a number of very large gaps in their biosecurity capabilities. Political will and resources must be mobilized so that all countries are better prepared for pandemic threats.

Collett: What do countries need to do to decrease the risk of a similar pandemic?

Cameron: One thing that all countries can and should do is undergo an external peer evaluation to identify and address their vulnerabilities. They should prioritize specific actions that can be taken to fill those gaps and then provide resources to keep those gaps filled over time.

This month, NTI is heading to the Global Health Security Agenda Ministerial hosed by Indonesia to encourage more action – especially on the components of the GHSA that focus on catastrophic risks, including intentional misuse and accidental release.

Collett: What are some examples of those gaps that countries could be looking for?

Cameron: I’ll give you a few examples under the headings of “Prevent,” “Detect,” and “Respond”. To “Prevent,” we’re focused at NTI on all countries knowing where their especially dangerous pathogens are located and taking steps to consolidate and prevent theft or misuse of them. As I mentioned previously, we know that almost no country in the world is fully prepared to accomplish this based on the external evaluations that have been conducted. Even well-developed countries fall short in this area. It’s also critical to improve accountability and oversight for research and technology development that can increase risk, including research that enhances virulence or transmissibility for pathogens that have pandemic potential. We’re working to do our part to reduce those risks through NTI’s Global Biosecurity Dialogue, Biosecurity Innovation and Risk Reduction Initiative, and Next Generation for Biosecurity Competition.

For “Detect,” we know that it’s really important for countries to have trained “disease detectives.” These are people that know how to find, stop, and prevent diseases from spreading. There are programs to train disease detectives all over the world and some of those disease detectives then go on to stop outbreaks in their own countries and regions. Also, the world is not yet prepared to detect emerging, unusual, and modified agents in real-time – I equate this to pulling a needle out of a haystack. It’s so vital to improve our international biosurveillance architecture so that we don’t lose precious time during a pandemic.

In “Respond,” we know that all countries should have in place the ability to have an emergency operations center – sort of a national hub for reporting when a disease is detected and then be able to run an effective outbreak response. The center should be able to be stood up quickly and it should be able to handle a report very quickly from anywhere in its territory. At this time, many countries don’t have an effective emergency operations center. In addition, there is not enough global attention or investment in developing the platforms necessary to more quickly develop, distribute, and dispense drugs and vaccines for emerging threats. New international efforts like the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) are helping, but additional focus and creative financing mechanisms remain crucial.

Collett: It seems like there’s still a lot of work to do. How is NTI | bio reducing the risk of a global pandemic in 2019 and beyond?

Cameron: NTI’s biosecurity program, NTI | bio is working on several things that are important to reducing global catastrophic biological risks and preventing the next pandemic. I’m really excited about NTI’s Global Biosecurity Dialogue. We know that most countries aren’t prepared to handle a deliberate or accidental biological event. That’s why we’re working with countries around the world to spur new actions to fill those biosecurity gaps worldwide. We’re working to also elevate this issue and build political will and financing to improve policy and capability gaps, while also addressing emerging risks. Additionally, I’m delighted to announce a new effort we recently launched called the Biosecurity Innovation and Risk Reduction Initiative. That Initiative is aimed at convening technical experts, people largely outside of governments, to determine new actions that can be taken to reduce the risks posed by advances in technology that make it easier to create and modify pathogens. Scientific advancements that allow the creation and modification of viruses like flu are outpacing the ability of national governments to provide effective oversight. This means the experts that create, use, and invest in new technologies should take additional and specific steps now to reduce those risks. The group has already agreed to pursue several novel approaches, which we hope will be piloted and eventually adopted in the coming years.

Next year, NTI, in cooperation with our partners at the Economist Intelligence Unit and the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, will also publish the first Global Health Security (GHS) Index. The GHS Index will be a catalog of areas for global attention and improvement to prevent the next outbreak from becoming a pandemic.

In addition, we remain focused on improving disease surveillance for emerging, unusual, and modified agents – those more likely to be associated with a global catastrophe but which are unexpected or deliberately created or released. Knowing what threat you’re dealing with is the first step to saving lives.

Collett: Those all sound so exciting! How can readers get involved with NTI | bio or just helping with this effort in general?

Cameron: There are several ways if you’re interested in becoming involved in pandemic preparedness of biosecurity. NTI readers come from all over the world, so, wherever you live, you can advocate for resources for pandemic preparedness. It’s really important that every country takes action to prevent, detect, and respond to disease outbreaks before they become epidemics. The US government, for example, has lots of programs that work nationally and internationally to stop outbreaks from becoming epidemics and that kind of continued work is really important.

You can also check out our Global Health Security Index when it’s published next year – we’re really excited to put forward the 1st global health security index with our partners and see how people can use the data to make the world safer.

Also, if you’re interested in our Global Biosecurity Dialogue, there is a Next Generation Global Health Security Network, and there’s a growing number of people in that network that are becoming interested in biosecurity so you could join that network and link up with biosecurity experts around the world.

Lastly, you could enter our Next Generation for Biosecurity Competition which we host annually to encourage young professional to think creatively about biosecurity and give them an opportunity to present their ideas to health security leaders from around the world. We will actually be announcing the 2018 competition winners in early November.

Stay Informed

Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest on nuclear and biological threats.

More on Atomic Pulse

Beyond Borders, Beyond Biases: Building a Biosecure Future with Diverse Voices

NTI | bio Senior Program Officer Dr. Aparupa Sengupta on why efforts to strengthen global biosafety and biosecurity must prioritize diversity and inclusion.

Identifying Outbreak Origins: How the Joint Assessment Mechanism Can Improve Pandemic Response

NTI is working with international partners to develop a new Joint Assessment Mechanism (JAM) within the office of the UN Secretary-General to rapidly identify outbreak origins. Without the ability to quickly determine the origin of an outbreak, researchers are hampered in their ability to rapidly develop vaccines and other medical countermeasures that can slow the pace of the outbreak, ultimately saving countless lives.

Democratic Strength as the Basis of Pandemic Response: a Review of the Covid Crisis Group Report

NTI | bio Senior Director Nathan Paxton on using democratic collaboration to improve pandemic security