Jacob H. Eckles

Senior Program Officer, Global Biological Policy and Programs

Atomic Pulse

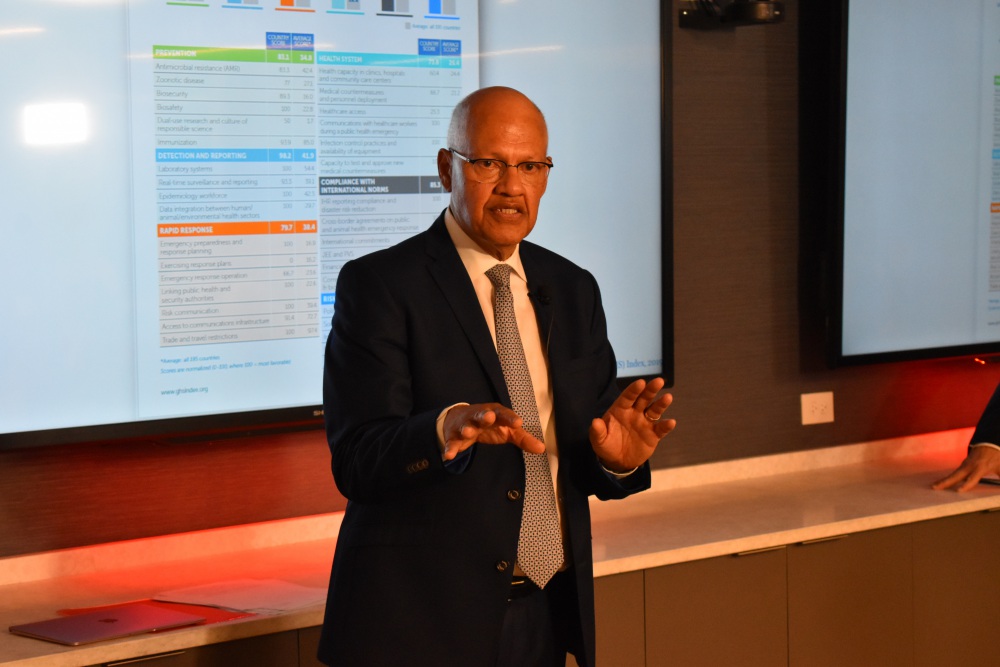

Wilmot James, a

visiting professor of political science and pediatrics at Columbia University, discussed challenges associated with

preventing, detecting, and responding to infectious disease outbreaks in challenging

circumstances at a January 15, 2020 NTI Seminar titled, “Battling Insecurity, Mistrust and Disease:

Are We Capable of Reining in Epidemics in Complex Environments?” A senior consultant to NTI | bio,

James was previously a Member of Parliament in South Africa, serving as

opposition spokesperson on schools, trade and health.

Professor James focused on three circumstances that pose

particular challenges for responders, governments and international

organizations trying to stop the spread of infectious diseases: when outbreaks

occur where government instability and conflict are prevalent such as in areas

of war where weak health infrastructure undermines local and international

response capability; in weak states with poor health leadership where communities

are left to handle outbreaks on their own; and when emerging threats from

climate change and biotechnology require critical attention from authorities unprepared to manage their impact.

War and Epidemics

Fighting epidemics in countries and regions plagued by

violence and instability poses perhaps the most substantial challenge, James

said. He cited recent data from the Global Health Security (GHS) Index, a

project of NTI and the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, in partnership

with The Economist Intelligence Unit, which shows more

than half of countries face major political and security risks that could

undermine national capability to counter biological threats.

James noted that war disrupts the delivery of health

services by public and private entities and creates circumstances where

pathogens can exploit gaps in health infrastructure. In addition, over time basic

health gains stall, populations become less healthy overall, and vaccination

rates drop. For example, the current Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic

of Congo has led to an explosion of measles cases in the region—310,000 measles

cases have been reported and 6,000 people have died since the start of 2019.

James argued that a new approach to security in Africa is

needed to stem outbreaks and deliver health services more reliably. While the

World Health Organization (WHO) can deliver some operational and logistical

support in crisis areas, much more is needed. Making more tangible gains in

combating epidemics in complex environments will require the United Nations,

African Union, regional bodies, and relevant domestic actors to come together

to find an enduring political solution for health security.

Health Leadership in Weak States

James also highlighted the importance of country and

community public health leadership to combat epidemics and improve global

health security. Governments typically have the authority, reach, and budgets

that allow for intervention to stop public health threats, but when governments

fail to act – either by negligence or inability – communities and citizens are

left to work out problems for themselves. When this happens, James said, communities

plunge into panic, creating social breakdown and mistrust. This is particularly

problematic with respect to newly emerging biological threats or agents that spread

at a surprising rate with a larger-than-expected geographic range. For example,

health workers on the front lines of the recent Ebola response have been met

with major resistance from local communities due to fear and mistrust bred over

years as a result of conflict. This has led to health workers being killed and the

burning of Ebola treatment centers, prolong the outbreak.

Public health leadership and trust can be built over time,

and James cited the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa

CDC) as one of the most promising agencies of the African Union. Recently, the

Africa CDC has established Regional Collaborating Centers (RCCs) which operate

as technical support institutions for the Africa CDC and work closely with the

Member States to build public health capabilities. NTI | bio has worked with

these RCCs, under the leadership of Africa CDC, to implement the Global

Biosecurity Dialogue in Africa, which has led to considerable

success in enabling countries to develop ways to address to critical biosafety

and biosecurity gaps in their country and across Africa.

A New Species of Trouble

Lastly, James warned of increasing risks associated with

deliberate or accidental biological events, with increasingly devastating

consequences. Using data from the GHS Index, he emphasized that the world is

underprepared for the emergence or release of pathogens; biosecurity and

biosafety indicators continue to show a lack of development globally,

particularly in Africa; and the entire world lacks controls around dual-use

research and must do more to develop a culture of responsible science.

NTI’s biosecurity program (NTI | bio) is working to combat

some of the greatest threats posed by these changes. The GHS Index helps spread

awareness – showing the world how much needs to be done, particularly on

biosecurity and biosafety – and it provides a resource for policy makers to

emphasize the need for investment in these preparedness gaps. The Global

Biosecurity Dialogue builds on these efforts, giving technical experts and policy

makers additional information, tools, and partnerships to advance biosafety and

biosecurity efforts globally. However, risks will continue to evolve and

increase as new technologies are developed and spread around the world. To

mitigate the high-consequence risk of an outbreak caused by an engineered

pathogen, whether accidental or deliberate, James encouraged governments to

consider designating a senior-level special facilitator or unit to stay ahead

of the game, particularly related to oversight of dual-use research as

technologies continue to advance.

Recommendations

James offered four

recommendations to address the issues he outlined:

This lecture was dedicated to Sheik Humarr Khan, an expert in the clinical care of viral

hemorrhagic fevers, who died aged 39 in Kailahun, Sierra Leone on July 29,

2014. Dr. Khan led Sierra Leone’s Ebola response. He served as the

Physician-in-Charge of the Kenema Government Hospital’s Lassa Fever Program and

saved more than 100 lives in the months he spent treating patients before

becoming infected himself.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest on nuclear and biological threats.

Examples from around the world of the Global Health Security Index in-use.

COVID-19 + Cybersecurity: Parallels and Lessons from a Pandemic

The U.S. and COVID-19: Leading the World by Score, not by Response