Iran Biological Overview

Background

This page is part of the Iran Country Profile.

- Click for Recent Developments and Current Status

Iran ratified the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BTWC) on 22 August 1973, and has publicly decried all weapons of mass destruction (WMD). 1 Although Iran has been accused by some countries of secretly developing an offensive BW program, most notably in the 1990s, more recent assessments have tended to avoid such definitive claims, instead emphasizing the dual-use capabilities inherent to Iran’s robust civil biotechnology sector. Available information indicates that Iran likely undertook some BW-related work in the past and, furthermore, that its capacity to pursue such a program has increased over time.

The main source of information regarding Iran’s BW activities and capabilities comes from statements and reports disseminated by U.S. intelligence agencies. In a 1996 report to the U.S. Senate, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) claimed that “Iran has had a biological warfare program since the early 1980s. Currently the program is in its research and development stages, but we believe Iran holds some stocks of BW agents and weapons.” 2 Likewise, the U.S. State Department noted in a 2003 and 2005 report that “Iran has an offensive biological weapons program in violation of the BWC. Iran is technically capable of producing at least rudimentary biological warheads for a variety of delivery systems, including missiles.” 3 However, more recent reports reveal less certainty. A 2011 report from the U.S. Director of National Intelligence (DNI) states that “Iran probably has the capability to produce some [BW] agents for offensive purposes, if it made the decision to do so. We assess that Iran has previously conducted offensive BW agent research and development. Iran continues to seek “dual-use technologies that could be used for BW.” 4 The 2015 State Department compliance report, the latest to mention Iran’s compliance with the BTWC, stated, “available information indicated that Iran continues to engage in dual-use activities with BW applications, but it is unclear if these activities were conducted for purposes inconsistent with the BWC.” 5

Capabilities

Dual Capable Infrastructure

Iran has a growing biotechnology sector that is one of the most advanced in the developing world. 6 Iran has long been recognized as a leader in Southwest Asia in several fields, including pharmaceuticals, vaccine research and development, and agricultural biotechnology. Dominant Iranian research interests in agricultural biotechnology involve improving crop resistance to pests and disease using genetically conferred anti-insect toxin production, discovery and development of new pesticides, anti-insect pheromone and hormone treatment, mycotoxin inhibition pesticide dissemination techniques, and mechanisms of plant damage and disease. 7

Iran also maintains three important health research facilities. While two of these facilities, the Pasteur Institute and the National Research Center of Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (NRCGEB), focus on human health, the third facility, the Razi Institute for Serum and Vaccines, studies both human disease and zoonoses. The Razi and Pasteur Institutes have pursued vaccine development and production since the 1920s, and for many years both of these facilities have been recognized as being among the most advanced of their kind in the developing world. Today, all three facilities host advanced microbiology and genetic engineering equipment and expertise.

Iran’s agricultural research priorities include both improving crop yields and reducing the threat to the country’s agricultural industry posed by pests and diseases. Iran’s work in the health sciences has enabled it to produce vaccines and innovative therapeutics. CinnoGen, the largest pharmaceutical company in the region, for example, was the first to produce a generic version of interferon beta-1a, a multiple sclerosis treatment, and remains one of only three producers of the treatment worldwide. However, the sophistication of the research techniques used, and their inherent relation to the biological processes that maintain human and crop health, raises some proliferation concerns. For example, the NRCGEB’s expertise in recombinant DNA technologies, genetic engineering, and DNA vaccine production could conceivably be utilized to research methods for increasing the virulence or resistance of select pathogens, and equipment for mass-producing vaccines and antiserums at the Pasteur Institute could be utilized to mass-produce biological weapons as well.

Strategic and Operational Aspects of Iran’s BW Capabilities

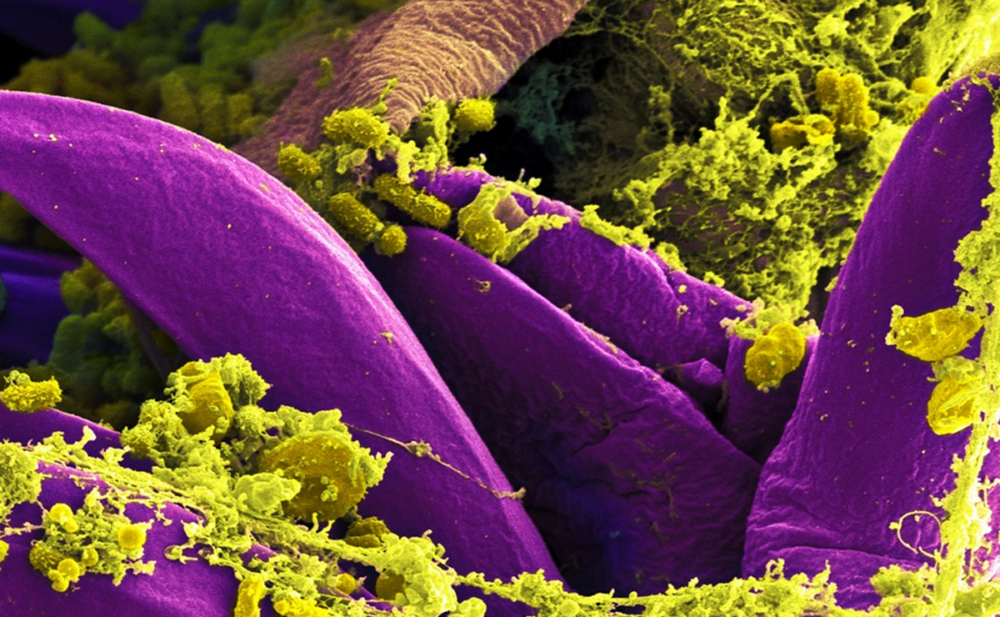

While the contents of the Persian Type Culture Collection (PTCC) had previously indicated that Iran possessed several agents that appear on the U.S. Select Agent list, including anthrax bacterium (Bacillus anthracis), plague bacterium (Yersinia pestis), and botulinum toxin, the current database no longer includes these agents. 8 Official assessments of Iran’s intentions regarding offensive BW vary. 9 In 2001, the U.S. Department of Defense asserted that Iran pursued BW expertise from Russia, and potentially held small stockpiles. 10 In 1996, the CIA claimed that Iran possessed weaponized biological agents that could be dispersed by artillery and aerial bombs. 11 However, more recent U.S. government reports do not specify which delivery methods Iran might use for biological weapons.

History

1980 to 2000: Evidence of Interest, Ambiguous Intentions

In addition to its domestic biological industries, Iran has imported several dual-use items from various countries, and cooperated extensively with Cuba in the realm of biotechnology. 12 The following section draws on allegations made by Western intelligence agencies and reports of Iran’s possibly BW-related imports.

Historically, Iran has indicated some interest in the acquisition of BW agents from foreign sources. In 1988, Hashemi Rafsanjani, the speaker of the Iranian parliament who was later elected President of Iran, publicly stated that “…we should fully equip ourselves in defensive and offensive use of chemical, bacteriological, and radiological weapons.” 13 The following year, Rafsanjani was elected the fourth President of Iran. In 2002, in a submission to the BTWC, Iran also declared that it “has carried out some defensive studies on identification, decontamination, protection, and treatment against some agents and toxins,” while also in the same submission denying that it had a “National Biological Defensive Program.” 14

Reports in the early 1990s claimed, without citing specific sources, that Iran at one time pursued the acquisition of castor beans (known to be used for producing the deadly toxin ricin), and that it additionally worked to develop botulinum toxin and anthrax. 15 These claims, however, remain unsubstantiated. Reports also circulated in 1989 indicating that Iran had attempted to procure Fusarium (a fungus that produces T-2 mycotoxins) from Canadian scientists. 16 Allegedly, the Iranian scientist who ordered the strains may have worked for the Imam Reza Medical Center. 17 A separate incident occurred when the Iranian Research Organization for Science and Technology allegedly attempted to order the same strains (in addition to nine others) from a facility in the Netherlands. 18 Both of these attempts were unsuccessful. Although it is unclear what the intended end-use of these materials might have been, both T-2 and trichothecene mycotoxins have the potential to be utilized as BW agents.

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Iran reportedly sought to hire former Soviet biological weapons scientists. 19 Scientists were allegedly approached with salary offers of up to $5,000 per month, which would have represented over five times their salaries at the time. 20 Although most of these efforts appear to have failed, dozens of scientists were approached and former Soviet biological weapons scientists reported at least five colleagues having left Russia to work in Iran. 21

2000 to 2010: Sanctions and Accusations

Since the passage of the Iran Nonproliferation Act in 2000, the U.S. government has levied sanctions against multiple companies for exporting dual-use goods to Iran. Some sources have linked two sanctioned Chinese companies to possible BW material based on the companies’ business activities. Oriental Scientific Instruments Corporation (OSIC), which was sanctioned by the United States in 2004, “manufactures a large array of pathological instruments and even supplies live monkeys and primates for biological research.” 22 This same source relates that another sanctioned Chinese company, Zibo Chemical Equipment Plant, exports spray-dryers, which are “critical for the manufacture of biological weapons such as anthrax and smallpox.” 23 The company’s English language website lists the following products: glass-lined reactors, tanks, heat exchangers, evaporators, columns, agitators, and double-cone rotary dryers, which could have multiple applications. 24 In 2009, reports surfaced of a confidential document recommending that the European Union (EU) sanction several entities “allegedly linked to Iran’s covert nuclear or biological weapons programmes.” 25 In accordance with the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), multilateral and unilateral sanctions on Iran are to be lifted. 26

Iran’s official position on the acquisition of biological weapons, and WMD in general, is summarized in its UN Security Council Resolution 1540 documents, which state, “the Islamic Republic of Iran considers acquiring, developing, and using WMD as inhumane, immoral, illegal, and against its very basic principles.” 27 In these reports, Iran also highlighted its efforts to combat biological weapons proliferation, including the relevant Islamic Penal Code (Article 688) and Ministry of Health and Medical Treatment and Education provisions.

In 2007, Iran presented to BTWC state parties evidence of laws and regulations it has enacted to counteract biological weapons proliferation, including the Environment Protection and Improvement Act of 1974 and the Importation and Exportation of Noxious and Poisonous Substances through Customs Act of 1988. 28 Iran points to its adoption of the Plant Protection Act in 1967 and the Iran Veterinary Organization Act of 1971 as examples of legislative steps it has taken to ensure the safeguarding of Iranian industries that come into contact with dual-use materials. 29 Iran also offered one of its premier facilities, the Razi Institute for Serums and Vaccines, to host trial inspections for the BTWC in 1998. 30 However, despite its proclaimed support for the BTWC, Iran did not submit Confidence Building Measures (CBM) as stipulated by the state parties to the BTWC until 1998, more than 10 years after these submissions began. 31 Moreover, when Iranian officials first submitted the declarations, “they conveniently ‘forgot’ to submit perhaps the two most critical CBM forms out of eight.” 32

Iran also has historically opposed international restrictions on its imports of dual-use biological materials. Specifically, Iran points to the Australia Group as exercising discriminatory controls on exports to Iran of dual-use biological materials and technology. 33

Recent Developments and Current Status

Iran’s biopharmaceutical industry has become increasingly sophisticated, and produces a variety of vaccines for humans and livestock. The Razi Institute for Serums and Vaccines and the Pasteur Institute are leading regional facilities in the development and manufacture of vaccines. In January 1997, the Iranian Biotechnology Society (IBS) was created to oversee biotechnology research in Iran. IBS has over 350 members and maintains several branches. Additionally, the Persian Type Culture Collection, a subordinate of the Biotechnology Institute of the Iranian Research Organization for Science and Technology, utilizes strains of yeast, fungus, and bacteria. 34 The website for the center states that it “operates according to international quality criteria,” and provides services to both private industry and academia. 35 Advanced research is also being carried out at the National Research Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology near Tehran.

The ambiguity surrounding the nature of Iran’s biological activities remains well summed up by the following three U.S. government assessments. In 2008, a senior Defense Intelligence Agency official reported: “Tehran continues to seek dual-use biotechnical materials, equipment and expertise which have legitimate uses, but also could enable ongoing biological warfare efforts.” 36 In 2011, the Director of National Intelligence reported “Iran probably has the capability to produce some biological warfare (BW) agents for offensive purposes, if it made the decision to do so. We assess that Iran has previously conducted offensive BW agent research and development. Iran continues to seek dual-use technologies that could be used for BW.” 37 In 2019, the Congressional Research Service concluded that while Iran likely possesses the capability to produce some BW agents, it is unlikely that it will use these capabilities or transfer them to regional proxies for fear of retaliation by international powers. 38

Stay Informed

Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest on nuclear and biological threats.

Glossary

- Ratification

- Ratification: The implementation of the formal process established by a country to legally bind its government to a treaty, such as approval by a parliament. In the United States, treaty ratification requires approval by the president after he or she has received the advice and consent of two-thirds of the Senate. Following ratification, a country submits the requisite legal instrument to the treaty’s depository governments Procedures to ratify a treaty follow its signature.

See entries for Entry into force and Signature. - Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BTWC)

- The BTWC: The Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production and Stockpiling of Bacteriological (Biological) and Toxin Weapons and on Their Destruction (BTWC) prohibits the development, production, or stockpiling of bacteriological and toxin weapons. Countries must destroy or divert to peaceful purposes all agents, toxins, weapons, equipment, and means of delivery within nine months after the entry into force of the convention. The BTWC was opened for signature on April 10, 1972, and entered into force on March 26, 1975. In 1994, the BTWC member states created the Ad Hoc Group to negotiate a legally binding BTWC Protocol that would help deter violations of the BTWC. The draft protocol outlines a monitoring regime that would require declarations of dual-use activities and facilities, routine visits to declared facilities, and short-notice challenge investigations. For additional information, see the BTWC.

- WMD (weapons of mass destruction)

- WMD: Typically refers to nuclear, biological, or chemical weapons, though there is some debate as to whether chemical weapons qualify as weapons of “mass destruction.”

- Biological weapon (BW)

- Biological weapons use microorganisms and natural toxins to produce disease in humans, animals, or plants. Biological weapons can be derived from: bacteria (anthrax, plague, tularemia); viruses (smallpox, viral hemorrhagic fevers); rickettsia (Q fever and epidemic typhus); biological toxins (botulinum toxin, staphylococcus enterotoxin B); and fungi (San Joaquin Valley fever, mycotoxins). These agents can be deployed as biological weapons when paired with a delivery system, such as a missile or aerosol device.

- Dual-use item

- An item that has both civilian and military applications. For example, many of the precursor chemicals used in the manufacture of chemical weapons have legitimate civilian industrial uses, such as the production of pesticides or ink for ballpoint pens.

- Offensive (research, weapon)

- Meant for use in instigating an attack, as opposed to defending against an attack.

- Pathogen

- Pathogen: A microorganism capable of causing disease.

- Anthrax

- The common name of the bacterium Bacillus anthracis, as well as the name of the disease it produces. A predominantly animal disease, anthrax can also infect humans and cause death within days. B. anthracis bacteria can form hardy spores, making them relatively easy to disseminate. Germany, the United Kingdom, the United States, and the USSR/Russia have all investigated anthrax as a biological weapon, as did the Japanese cult Aum Shinrikyo. Anthrax-laced letters were also used to attack the U.S. Senate and numerous news agencies in September 2001. There is no vaccine available to the general public, and treatment requires aggressive administration of antibiotics.

- Plague

- Plague: The disease caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis. There are three forms of plague: bubonic plague, pneumonic plague, and septicemic plague. Bubonic plague refers to infection of the lymph nodes by Y. pestis, causing black sores or “buboes,” pneumonic plague refers to infection of the lungs, and septicemic plague refers to infection of the bloodstream. Although no longer a serious public health hazard in the developed world, the bacterium can spread from person-to-person in aerosolized form, and has been investigated as a biological weapon by Japan and the Soviet Union.

- Botulinum Toxin

- Botulism is caused by exposure to botulinum toxin (a neurotoxin). Most often caused by eating contaminated foods, botulinum poisoning prevents the human nervous system from transmitting signals, resulting in paralysis, and eventually death by suffocation. Botulinum toxin is the most toxic known substance. 15,000 times more toxic than VX nerve gas, mere nanograms of botulinum toxin will kill an adult human. A significant bioweapons concern, botulinum toxin has been investigated as a weapon by Japan, the Soviet Union, the United States, Iraq and unsuccessfully by the Japanese cult Aum Shinrikyo.

- Chemical Weapon (CW)

- The CW: The Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons defines a chemical weapon as any of the following: 1) a toxic chemical or its precursors; 2) a munition specifically designed to deliver a toxic chemical; or 3) any equipment specifically designed for use with toxic chemicals or munitions. Toxic chemical agents are gaseous, liquid, or solid chemical substances that use their toxic properties to cause death or severe harm to humans, animals, and/or plants. Chemical weapons include blister, nerve, choking, and blood agents, as well as non-lethal incapacitating agents and riot-control agents. Historically, chemical weapons have been the most widely used and widely proliferated weapon of mass destruction.

- Sanctions

- Punitive measures, for example economic in nature, implemented in response to a state's violation of its international obligations.

- Multilateral

- Multilateral: Negotiations, agreements or treaties that are concluded among three or more parties, countries, etc.

- UNSC Resolution 1540

- Resolution 1540 was passed by the UN Security Council in April 2004, calling on all states to refrain from supporting, by any means, non-state actors who attempt to acquire, use, or transfer chemical, biological or nuclear weapons or their delivery systems. The resolution also called for a Committee to report on the progress of the resolution, asking states to submit reports on steps taken towards conforming to the resolution. In April 2011, the Security Council voted to extend the mandate of the 1540 Committee for an additional 10 years.

- Proliferation (of weapons of mass destruction)

- The spread of biological, chemical, and/or nuclear weapons, and their delivery systems. Horizontal proliferation refers to the spread of WMD to states that have not previously possessed them. Vertical proliferation refers to an increase in the quantity or capabilities of existing WMD arsenals within a state.

- Confidence- (and Security-) Building Measures (CSBMs)

- Confidence- (and Security-) Building Measures (CSBMs): Tools that states can use to reduce tensions and avert the possibility of military conflict. Such tools include information (e.g., the size of military forces); communication (e.g., "hot lines" or direct lines between capitals); constraints (e.g., demilitarized zones); notification (e.g., prohibitions on activities that have not been notified in advance); and access (e.g., on-site inspections) measures. CSBMs normally precede the negotiation of formal arms control agreements or are added to arms control agreements to strengthen them. See entries for Arms Control, Transparency Measures, and Verification.

- Australia Group (AG)

- Australia Group (AG): Established in 1985 to limit the spread of chemical and biological weapons (CBW) through export controls on chemical precursors, equipment, agents, and organisms. For additional information, see the Australia Group.

Sources

- "Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, and Stockpiling of Bacteriological (Biological) and Toxin Weapons and on their Destruction - Status of the Treaty," United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs, http://disarmament.un.org; See "Annex to the Note Verbale Dated 28 February 2005 from the Permanent Mission of the Islamic Republic of Iran to the United Nations Addressed to the Chairman of the Committee," 1 March 2005, http://daccess-dds-ny.un.org. "The Islamic Republic of Iran considers acquiring, developing, and using WMD as inhumane, immoral, illegal, and against its very basic principles" and Hossein Aryan, "Commentary: Iran's Hard-Liners Look to Justify a Nuclear Arsenal," 16 February 2010, www.globalsecurity.org.

- Central Intelligence Agency, "Current and Projected National Security Threats to the United States and its Interests Abroad," written responses to questions before the Select Committee on Intelligence of the United States Senate, Hearing 104-510, 22 February 1996, www.fas.org.

- Bureau of Arms Control, Verification, and Compliance, Adherence to and Compliance with Arms Control, Nonproliferation, and Disarmament Agreements and Commitments, U.S. Department of State, August 2005, p. 20, www.state.gov.

- "Unclassified Report to Congress on the Acquisition of Technology Relating to Weapons of Mass Destruction and Advanced Conventional Munitions, Covering 1 January 1 to 31 December 2011," U.S. Director of National Intelligence, p. 4, http://fas.org.

- Bureau of Arms Control, Verification, and Compliance, Adherence to and Compliance with Arms Control, Nonproliferation, and Disarmament Agreements and Commitments, U.S. Department of State, 5 June 2015, www.state.gov.

- Office of the Secretary of Defense, "Proliferation: Threat and Response, U.S. Department of Defense," distributed by Federation of American Scientists, January 2001, pp. 33-35.

- Behzad Ghareyazie, "Iran: Hopes, Achievements, and Constraints in Agricultural Biotechnology," in Gabrielle J. Persley and M.M. Lantin, eds., Agricultural Biotechnology and the Poor: Proceedings of an International Conference, (21-22 October 1999, Washington, D.C., USA), pp. 100-104.

- The current PTCC database does not include the following previous entries: anthrax bacterium (Bacillus anthracis), plague bacterium (Yersinia pestis), aflatoxin, ricin toxin, and botulinum toxin. The PTCC does, however, includes pathogens previously used in biological warfare, such as typhoid bacterium (Salmonella Typhi) and cholera bacterium (Vibrio cholerae) as well as agents that could be used to simulate biological weapons. See: Research and Technology, Iranian Research Organization for Science and Technology (IROST), "Persian Type Culture Collection," Ministry of Science, accessed 29 June 2011, www.irost.org.

- Anthony Cordesman, "Iranian Weapons of Mass Destruction: Biological Weapons Programs, Weapons of Mass Destruction in Iran," Working Draft for Review and Comments, Center for Strategic and International Studies, 28 October 2008.

- Office of the Secretary of Defense, Proliferation: Threat and Response, U.S. Department of Defense, January 2001, pp. 33-35.

- Barbara Starr, "Iran Has Vast Stockpiles of CW Agents, Says CIA," Jane's Defense Weekly, 14 August 1996, p. 3.

- Dana Garrett, "Iran Grants Cuba 20-million Euro Credit," Havana Journal, 18 January 2005, http://havanajournal.com; "Iran, Cuba Sign Trade Memorandum of Understanding," Tehran Times, 19 June 2008, www.tehrantimes.com; "Arms Control and Proliferation Profile: India," Arms Control Association, www.armscontrol.org.

- Gregory F. Giles, "The Islamic Republic of Iran and Nuclear, Biological, and Chemical Weapons," in Peter R. Lavoy, Scott D. Sagan, and James J. Wirtz, eds., Planning The Unthinkable: How New Powers Will Use Nuclear, Biological, and Chemical Weapons (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2000), p. 84.

- Iranian CBM Submission to the BTWC, 2002, as quoted in Milton Leitenberg, Assessing the Biological Weapons and Bioterrorism Threat, Strategic Studies Institute, December 2005, www.strategicstudiesinstitute.army.mil.

- The report does not clearly state whether the castor beans were acquired for BW purposes or simply to derive castor oil. The potential for illicit application of castor beans, however, makes it worth mentioning in this section. See Eric Croddy et. al., Weapons of Mass Destruction: An Encyclopedia of Worldwide Policy, Technology, and History (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, Inc., 2005), p. 241; Michael Eisenstadt, The Deterrence Series: Chemical and Biological Weapons and Deterrence, Case Study 4: Iran, Chemical and Biological Arms Control Institute, 1998, p. 2; and Douglas Waller, "Sneaking in the Scuds," Newsweek, June 22, 1992, www.newsweek.com. For information on the second half of this sentence, see: Jonathan B. Tucker, "Dual-Use Toxins: Dilemmas of a Dual-Use Technology: Toxins in Medicine and Warfare," Politics and the Life Sciences, February 1994 and Anthony Cordesman, et. al., "Iranian Weapons of Mass Destruction: Biological Weapons Programs," Center for Strategic and International Studies, http://csis.org.

- Michael R. Gordon and Stephen Engelberg, "Iran Is Said to Try to Obtain Toxins," The New York Times, 13 August 1989, www.nytimes.com.

- Michael R. Gordon and Stephen Engelberg, "Iran Is Said to Try to Obtain Toxins," The New York Times, 13 August 1989, www.nytimes.com.

- Michael R. Gordon and Stephen Engelberg, "Iran Is Said to Try to Obtain Toxins," The New York Times, 13 August 1989, www.nytimes.com.

- Linda D. Kozaryn, "Former Soviets' Bio-War Expert Details Threat," American Forces Press Service, U.S. Department of Defense, 3 November 1999, www.defense.gov; Anthony H. Cordesman and Adam C. Seitz, Iranian Weapons of Mass Destruction: The Birth of a Regional Arms Race? (USA: Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2009), p. 173.

- Judith Miller, Stephen Engelberg, and William Broad, Germs: Biological Weapons and America's Secret War, (New York: Simon & Schuster 2001), p. 206.

- Judith Miller and William J. Broad, "Bio-Weapons in Mind, Iranians Lure Needy Ex-Soviet Scientists," New York Times (Moscow), 9 December 1998, www.nytimes.com.

- Charles R. Smith, "Bush Sanctions Chinese Firms' WMD Exports to Iran," Newsmax, 8 April 2004, http://archive.newsmax.com.

- Charles R. Smith, "Bush Sanctions Chinese Firms' WMD Exports to Iran," Newsmax, 8 April 2004, http://archive.newsmax.com.

- Zibo Chemet Equipment Co., Ltd., www.chemet.net.

- Guy Dinmore, et.al., "EU Trio Targets Tougher Iran Sanctions," Financial Times, 25 February 2009, www.ft.com.

- Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, U.S. Department of State, www.state.gov.

- "Note Verbale Dated 28 February 2005 from the Permanent Mission of the Islamic Republic of Iran to the United Nations Addressed to the Chairman of the Committee," UN Security Council, 1 March 2005, http://daccess-dds-ny.un.org.

- "National Laws and Regulations on Handling and Application of Biological Agents and Toxins," Meeting of the States Parties to the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production and Stockpiling of Bacteriological (Biological) and Toxin Weapons and on Their Destruction, 23 August 2007, www.brad.ac.uk.

- "Note Verbale Dated 14 February 2006 from the Permanent Mission of the Islamic Republic of Iran to the United Nations Addressed to the Chairman of the Committee," UN Security Council, 18 February 2006, http://daccess-dds-ny.un.org; "National Laws and Regulations on Handling and Application of Biological Agents and Toxins," Meeting of the States Parties to the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production and Stockpiling of Bacteriological (Biological) and Toxin Weapons and on Their Destruction, 23 August 2007, www.brad.ac.uk.

- "Report of a National Trial Visit to a Vaccine and Serum Production Facility," Ad Hoc Group of the States Parties to the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production and Stockpiling of Bacteriological (Biological) and Toxin Weapons and on their Destruction, 14 January 1999, www.opbw.org.

- Nicolas Isla and Iris Hunger, "BWC 2006: Building Transparency through Confidence Building Measures," Arms Control Today, July 2006, www.armscontrol.org.

- The forms not submitted "were the declarations that require the state to list national biological defense research and development programs (Form A2) and past activities in offensive/defense biological research and development programs (Form F)." This may be connected with Iran's later claim that it does not have a "National Biological Defensive Program." Milton Leitenberg, Assessing the Biological Weapons and Bioterrorism Threat, Strategic Studies Institute, December 2005, www.strategicstudiesinstitute.army.mil.

- Martin Matishak, "U.S. to Announce Framework for Bioweapons Treaty Policy in Geneva," Global Security Newswire, 4 December 2009, www.globalsecuritynewswire.org; "China, Iran Oppose Ban on Biological Weapons," United Press International, 9 May 2001.

- According to its Web site, the Iranian Biotechnology Society "presently has 356 members. 102 of them are regular, 77 affiliated, 173 students and some institutional members." See http://ibs.nrcgeb.ac.ir.

- Ministry of Science, Research and Technology, Iranian Research Organization for Science and Technology Web site, "Persian Type Culture Collection," www.irost.org.

- Lt. Gen. Michael Maples, "Current and Projected National Security Threats to the United States," 28 February 2008, p. 12, www.dia.mil.

- "Unclassified Report to Congress on the Acquisition of Technology Relating to Weapons of Mass Destruction and Advanced Conventional Munitions, Covering 1 January to 31 December 2011," U.S. Director of National Intelligence, p. 4, http://fas.org.

- Kenneth Katzman, "Iran's Foreign and Defense Policies," Congressional Research Service, 8 October 2019, www.fas.org.